Slide 14

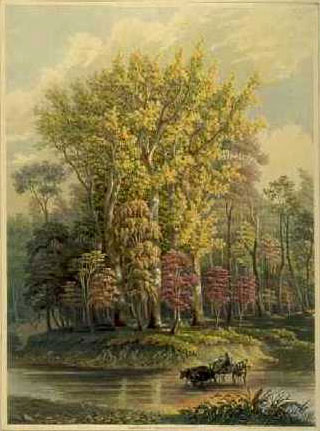

"Owl Creek, Ohio" by Washington Irving

Aquatint by George Harvey

1841

(image from www.library.yale.edu/beinecke/spirit1.htm)

Early American author Washington Irving would also leave a wonderful description of this area, which accompanied a colored aquatint by George Harvey in his Scenes of the Primeval Forests of America.

In a single night of October, a sudden frosty wind will alter the whole complexion of the woodland scenery. Before the next day’s sun has reached its meridian, the sycamores, from a light cheerful green, have changed to a golden yellow–the maples have put on a rich livery of orange and scarlet–the dog-wood has assumed a varied crimson–the deep green of the elm is succeeded by a russet yellow-the red and black oaks have taken the colors indicated by their respective names, and the horse-chesnut, or "Buckeye," is of a brilliant brown cinnabar. We will now turn to the engraving. It is a study of trees, made on the name of Owl Creek Ohio... The sycamores, or plane-trees, in the view, are of gigantic growth, measuring not less than eight feet in diameter. The two dog-wood trees have also attained their largest size. The stream is represented is shallow, but in spring-time, when the winter’s snow is dissolving, attended with heavy rains, it will overflow its banks, and inundate the rich bottom-lands in its passage, giving the additional fertility for which they are known throughout the state.

It is a fine Autumnal afternoon, and if my reader will accompany me, we will wander along its shores, skipping from rock to rock, or picking our way among rounded moss covered stones, and occasionally walking leisurely over a fine gravelly strand, which we find always on the eddying side. Let us climb this rugged bank, and now that we are above we see more perfectly the mirrored picture. How beautiful it is! Now we will cross through the woods and emerge again three miles below–we are no longer enveloped in the tangled mass of underwood which grows along the margin of the stream. Here, on this prostrate tree, let us rest awhile, and meditate on the weary pilgrimage this little stream at our feet must perform before it mingles with the ocean. Thus, for fifty miles, it continues its obscure and modest course, under its own but humble name of Owl Creek. Then, having formed a junction with the Mohiccon, it is known as White Woman’s Creek for fifty miles further, when it enters the Muskingum. Now, enlarged into an ample volume, it rolls onward for ninety miles to Marietta, where it unites itself with the Ohio. Forming a part of this beautiful and majestic river, it winds gracefully but proudly for eight hundred miles, until it glides into the turbid and overwhelming tide of the Mississippi; and then has eleven hundred miles of journeying to make before it empties itself into the Gulf of Mexico; making altogether a pilgrimage of upwards of two thousand miles! Does not your respect for this little pilgrim stream rise as you learn the great career it has to run, and the mighty fellowship in which it has to mingle:–but such is an emblem of human life–and many a one who has made the most noise in the world, and filled the greatest space in the public eye, has had no greater beginning than little Owl Creek.