Introduction

Introduction

Methodology

Methodology

Cynthia Barker

Cynthia Barker

Ruhamah Hayes

Ruhamah Hayes

Hannah Longbon

Hannah Longbon

Mary Steinhauer

Mary Steinhauer

Mary Chase

Mary Chase

Sophia Chase

Sophia Chase

Amelia Bloomer

Amelia Bloomer

Related Links

Related Links

Credits

Credits

Home

Home

Introduction

Nineteenth Century American Women

The nineteenth century American woman found her identity in her housework, her husband, and her children. Social and legal constraints limited the woman almost exclusively to these roles in the early part of the nineteenth century. While her husband tended the public sphere, the woman cared for her family and home, the private sphere. This connection to domestic and family life gave rise to the "cult of true womanhood" in which women of the time were expected to embody four essential virtues: piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity.

1. Piety was the "core of a woman’s virtue, the source of her strength." (Welter 21) All other virtues would necessarily follow. Women were expected both to uphold religious virtue within their own homes and to spread religion to others. They were the "handmaid[s] to the Gospel" whose job it was to ensure the piousness of the rest of their society. Piety, therefore, gave women "something to do" and the church reinforced all other qualities of "true women." (Welter 22) Without piety first and foremost, a woman was "unnatural and unfeminine, in fact, no woman at all." (Welter 23)

|

Modern interpretations of 19th

|

2. Since men "would sin and sin again, they could not help it", purity rested on the shoulders of the women, the "stronger and purer" sex. (Welter 24) Several ladies’ journals and magazines of the nineteenth century written by women gave instructions and suggestions to women on how to avoid betraying their virtuous nature. Ms. Eliza Farrar gave such advice in The Young Ladies’ Friend: "Sit not with another in a place that is too narrow; read not out of the same book; let not your eagerness to see anything induce you to place your head close to another person’s." (Welter 24)

3. Submissiveness of women was divinely-ordained in Ephesians 5:22-23. Pious as they were, women were expected to accept their submissive state willingly, as their nature lent itself to passivity. Marriage was the ultimate acceptance of such a station of life, since women thought that they needed to marry in order to be happy for themselves, but also that it was necessary to make men happy, and essential for the man’s success in whatever he might do.

|

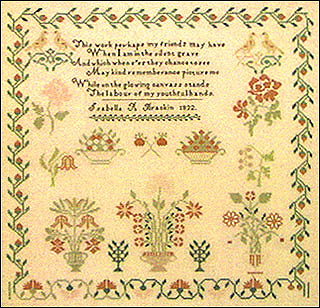

Samplers displayed the sewing

|

4. Domesticity was the area of life in which women alone were allowed to shine and one of the only ways in which women really had any influence of decision-making over the family. Housework was considered good physical exercise, mentally uplifting for a woman in having performed a job well-done, and absolutely necessary so that her husband could fulfill his duties outside the home. (Welter 37-8) In addition to taking care of the home and housework itself, overseeing the household also included meeting the needs of the family while tending to medical concerns, cooking, education (religious and secular), and other general management.

These four qualities constituted the "true" woman of the nineteenth century. In light of industrialization, urbanization, social reforms (including the Women’s Rights Movement), etc., women who preserved all four of these standards were considered especially valuable and desirable as wives.

These same social advances along with technological innovation allowed women to accomplish their household chores more quickly and to turn to activities which they otherwise would never have been able to do, therefore achieving some sense of feminine independence. The following is an article entitled "Feminine Freedom" from Godey’s Lady’s Book, November, 1896.

Woman's emancipation was for many years a sentimental vagary; now it is an accomplished fact. This is not so much due to advanced ideas, as to the labor-saving inventions of the age, most of which have emanated from the creative brain of man.

Our grandmothers planted their own flax, spun their own thread, wove their own cloth, and shaped their own garments. Before the days of sewing machines they stitched unceasingly, and to know how to sew was a necessity rather than an accomplishment. Now the whizz of the treadle is heard in every home, and the busy seamstress accomplishes in a day what she could not have done in a month.

Wringers, patent soaps, and stationary tubs have released the aching arms of the laundress from the drudgery of washing; the housemaid lightly runs her sweeper over the carpet and disdains to handle the honest broom; the cook turns up her nose at the homely kitchen range and broils and bakes by gas or electricity; the dairymaid's occupation is gone, as the cream is separated and the butter churned by machinery; the busy housekeeper need no longer put up her fruit and pickles, as that is done at the factory.

In fact, in this mechanical age, human hands seem almost superfluous, and the labor-saving devices so numerous, that women are no longer bound like Ixion to the wheel of household drudgery.

The one busy housekeeper released from the thraldom of baking, sweeping, and washing, has leisure to keep herself posted about current events, the newest book, and the latest fad in art, music, or fashion. The old regime has passed away, and women, no longer hampered by household cares, stand forth the peers of their husbands and brothers in education and enlightenment. (Women's Issues website)

As the final paragraph indicates, women believed that they were closer to being on par with men in more widely-important matters than the home. Their newfound confidence and knowledge of the outside world, and free time allowed women to take jobs. To most women these jobs were the final step in their search for freedom. To a few women, however, possessing some of the same knowledge as men and being allowed to work outside the home simply was not enough. The most determined of these women became leaders of the Women’s Rights Movement. Even these women, however, expected only certain freedoms and rights, and were still confined in some ways to the "cult of true womanhood."

The women who believed very strongly in equal rights in every way for women were primarily looked down upon and condescended to for trying to do "man’s work". If married (and most women were) these women still ultimately answered to their husbands and were subject to his decisions on how to run both of their lives. These women who were so active were clearly the exceptions; for the majority of women, though, acceptable jobs for women were limited to teaching, sewing, and others which were still closely-tied to their duties as good wives and mothers.

Nineteenth Century Ohio

When early American settlers decided that their land along the East Coast could no longer contain the growing population and its interests, they headed westward. Ohio lay directly in the path of New Englanders’ migration and the Great Lakes and Ohio River

|

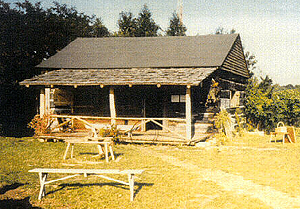

An early frontier cabin |

created natural barriers to the settlers’ travel. In 1787, Ohio was organized for settlement, thought the federal government had been granting parcels of Ohio land to Revolutionary War Veterans for years prior to its formal organization.

Ohio offered tremendous opportunities for its new settlers: fertile land, ample wildlife, and abundant vegetation. The frontier was not without its problems, however; the settlers were subject to Native American Indian attacks, there were no modern amenities, and the forests of Ohio were impassable. Settlers intent on making Ohio their home were willing to cope with these problems in order to build new lives for their families.

Nineteenth Century Ohio Women

Women were especially important on the Ohio frontier. There was plenty of work for all the family to do to create their homestead, but women worked toward establishing their homes, tended to the needs of their family, and still took over their husbands' affairs while they were away. A woman’s help was so essential that if a man’s wife passed away, he was forced to remarry as soon as possible because he alone could not manage his own business, his children, home, and farm.

|

The interior of a typical frontier cabin |

Frontier women, though expected to be tough and resilient, were also expected to maintain the four virtues of the "cult of true womanhood." When families migrated to Ohio their first concern was establishing the site of their home and farm to create shelter and a steady food supply. Other buildings, namely churches, were of secondary concern. There were also few religious leaders on the frontier; these conditions forced the women of the frontier to be the sole religious educators for their families, a responsibility taken seriously by all. With so few neighbors (if any), and few opportunities for gatherings, purity was a virtue relatively easily kept. Frontier life also made submissiveness simple enough, for there was nowhere for women to go and no one to see–very few ways for women to rebel against the men of their lives. Domesticity was necessary, for without a woman’s hard work, her family would go hungry and her house and farm would fall to ruin and rot. She would suffer equally with her family; therefore, domesticity was imperative for a woman in order to stave off her own misfortune.

As frontier establishments grew, more opportunities opened for women to meet with other women, attend church, socials, and public events, and to broaden their interests beyond their farms. Nineteenth century central Ohio, therefore, saw a broad spectrum of women, from those who clearly exemplified the "cult of true womanhood" to those who preached to other women to abandon such ideas, quite a new thought for women on the Ohio frontier.