Introduction

Introduction

Methodology

Methodology

Cynthia Barker

Cynthia Barker

Ruhamah Hayes

Ruhamah Hayes

Hannah Longbon

Hannah Longbon

Mary Steinhauer

Mary Steinhauer

Mary Chase

Mary Chase

Sophia Chase

Sophia Chase

Amelia Bloomer

Amelia Bloomer

Related Links

Related Links

Credits

Credits

Home

Home

Amelia Bloomer

Amelia Jenks Bloomer was born in Homer, New York, in 1818. Though she herself was only formally-educated for two years, she taught school and was thought remarkably intelligent by her peers. At age twenty-two, in 1840, she married lawyer Dexter Bloomer. By his encouragement, Amelia began writing articles in support of prohibition and women’s rights for his paper, The Seneca Falls Courier. Her interests led her to join several temperance groups and women’s rights organizations in the Seneca Falls area, even taking her to the famous Seneca Falls Convention in 1848.

|

Amelia Bloomer |

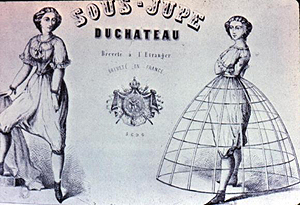

In January, 1849, encouraged by women’s rights leaders such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, Amelia Bloomer published the first edition of her own newspaper, The Lily, devoted entirely to women’s issues (and what she thought to be women’s issues), including suffrage, temperance, education, and fashion. Amelia’s dedication to such issues even compelled her to become part of a women’s dress reform. She became noted during her travels to give lectures for wearing billowy, full-length pants, gathered at the ankles, with a short skirt over it. Some thought her attire unbecoming of a woman, inappropriate, and simply ridiculous. Bloomer, however, even went so far as to defend her pants in The Lily; though she was not the first to wear them, her avid endorsement linked her name to the garb forever, "bloomers." Unfortunately, too, since Amelia continued wearing bloomers for so long after other feminists had abandoned them in the fear that their concerns for women would not be taken seriously, her own efforts on behalf of women were impaired.

|

An early bloomers ad |

Bloomer continued to publish The Lily in spite of waning support and even held the position of deputy postmistress in Seneca Falls. When she and her husband moved to Mt Vernon, Ohio, in 1854, she kept her newspaper, and aided him with the publication of his paper, the Western Home Visitor. The Bloomers remained in Mt Vernon for only a year, before Dexter decided to sell his paper and move to Council Bluffs, Iowa. Amelia also sold The Lily, but continued to help her husband with his work and still gave lectures and wrote for other papers. Amelia’s dedication to women’s rights lasted until her death in 1894 at Council Bluffs.

Amelia Bloomer was, of course, an exception to the nineteenth-century rule for women. She and her husband had moved from a far more progressive place than most Ohio settlers had, so when she arrived in the newly-established Mt Vernon, the ideas which she expressed in the Western Home Visitor were met not only with skepticism, but outright criticism of her, her womanhood, and even her husband for "allowing" her to write such things. The following is an excerpt from her salutatory article in the Western Home Visitor.

Woman’s Right to Employment. To woman equally with man has been given the right to labor, the right to employment for both mind and body; and such employment is as necessary to her health and happiness, to her mental and physical development, as to his. All women need employment, active, useful employment; and if they do not have it, they sink down into a state of listlessness and insipidity and become enfeebled in health and prematurely old simply because denied this great want of their nature. Nothing has tended more to the physical and moral degradation of the race than the erroneous and silly idea that woman is too weak, too delicate a creature to have imposed upon her the more active duties of life,–that it is not respectable or praiseworthy for her to earn a support or competence for herself.

We see no reason why it should be considered disreputable for a woman to be usefully employed, while it is so highly respectable for her brother; why it is so much more commendable for her to be a drone, dependent on the labors of others, than for her to make for herself a name and fortune by her own energy and enterprise. A great wrong is committed by parents toward their daughters in this respect. While their sons as they come to manhood are given some kind of occupation that will afford not only healthy exercise of the body and mind but also the means of an honorable independence, the daughters are kept at home in inactivity and indolence, with no higher object in life than to dress, dance, read novels, gossip, flirt and ‘set their caps’ for husbands. How well the majority of them are fitted to be the companions and mothers of men, every day’s history will tell.

...[Women] eat, they drink, they sleep, they dress, they dance and at last die, without having accomplished the great purposes of their creation. Can woman be content with this aimless, frivolous life?...While all other things both animals and vegetable perform their allotted parts in the universe of being, shall woman, a being created in God’s own image, endowed with reason and intellect, capable of the highest attainments and destined to an immortal existence, alone be an idler, a drone, and pervert the noble faculties of her being from the great purposes for which they were given?

Announcement appearing in the Ohio State Times in 1854

It will not always be thus; the public mind is undergoing a rapid change in its opinion of woman and is beginning to regard her sphere, rights and duties in altogether a different light from that which she has been viewed in the past ages. Woman herself is doing much to rend asunder the dark veil of error and prejudice which has so long blinded the world in regard to her true position; and we feel assured that, when a more thorough education is given to her and she is recognized as an intelligent being capable of self-government, and in all rights, responsibilities and duties man’s equal, we shall have a generation of women who will blush over the ignorance and folly of the present day. –A.B. (Bloomer, 161-2)

This article (and many more like it published in the same paper) was considered inflammatory by local readers, both men and women. Surprisingly, however, subscriptions to The Lily rose. The difference between the two papers was that the readers of The Lily expected to read such an article, and in fact, would have been disappointed with anything more timid or less honest. Her letters in The Lily sometimes even reached accusatory peaks. Bloomer was outraged at the treatment of women, but especially of wives. The following article, entitled "Golden Rules for Wives" was published in The Lily, displaying her outrage at husbands’ treatment of their wives.

Faugh, on such twaddle! ‘Golden rules for wives’–‘duty of wives’–how sick we are at the sight of such paragraphs! Why don’t our wise editors give us now and then some ‘golden rules’ for husbands, by way of variety? Why not tell us of the promises men make at the altar, and of the injunction ‘Husbands, love your wives as your own selves’? ‘Implicit submission of a man to his wife is disgraceful to both, but implicit obedience of the wife to the will of the husband is what she promised at the altar.’ So you say! What nonsense! what absurdity! what downright injustice! A disgrace for a man to yield to the wishes of his wife, but an honor for a wife to yield implicit obedience to the commands of her husband, be he good or bad, just or unjust, a kind husband or a tyrannical master! Oh! how much of sorrow, of shame and unhappiness have such teachings occasioned. Master and slave! Such they make the relationship existing between husband and wife; and oh, how fearfully has woman been made to feel that he who promised at the altar to love, cherish and protect her is but a legalized master and tyrant! We deny that it is any more her duty to make her husband’s happiness her study than it is his business to study her happiness. We deny that it is woman’s duty to love and obey her husband, unless he prove himself worthy of her love and unless his requirements are just and reasonable. Marriage is a union of two intelligent, immortal beings in a life partnership, in which each should study the pleasure and the happiness of the other and they should mutually share the joys and bear the burdens of life. (Bloomer, 151-4)

After a few months in Mount Vernon, Dexter Bloomer decided to sell his paper and move westward, finally settling on Council Bluffs, Iowa. In spite of her support for equal rights for women, Amelia Bloomer followed the wishes of her husband and sold The Lily to move with him. To the modern observer, Amelia’s ability to reconcile her role as women’s rights advocate and her role as a dutiful wife, seems contradictory. Bloomer, however, considered her leaving The Lily an act of love, and not obedience. In her farewell letter, she wrote: "But the Lily, being as we conceive of secondary importance, must not stand in the way of what we believe our interest. Home and husband being dearer to us than all beside, we cannot hesitate to sacrifice all for them[.]" (Bloomer, 189)