|

|

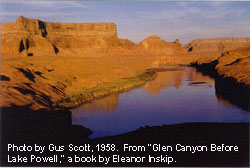

The Colorado River of fifty years ago was a completely different site than what one finds today. It was the first river to be taken under complete human control, a feat Floyd Dominy, then Head of the Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) is extremely proud of (PBS,1997). The extent of control over the river is such that, except for in extremely wet years, the Colorado River literally does not reach the sea. So far this year, the Colorado River has reached the Gulf of Cortez twice (Dave Wegner,Personal Communication). The loss of the estuary and other environmental impacts, which occur all along the river itself, have drastically altered the natural state of the Colorado River system. These changes, while it is arguable that all not are bad, highlight the enormous extent to which we impact our earth and the need for extensive research before and after our actions.

Before Dominy's time, the turbid, sediment laden water rushed through canyons at speeds between 80,000 to 100,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) during annual floods. Fed each year by annual ice melts and rare violent storms, seasonal temperatures ranged from 40 to 80 degrees Fahrenheit (USBR, 1996). High velocity waters scoured canyon walls cleansing debris from its path, removing sediments laced with high contents of trace minerals that when accumulated become toxic to the system (Glen Canyon Institute, 1998), all the while further developing the depth and magnitude of the canyons. The extreme and volatile nature of the Colorado provided good habitat for carp, catfish, razorback and bluehead suckers, humpback and bonytail chub, speckled dace and the Colorado squawfish, most of which are endangered today (NPS, 1998). Today, while boaters and other water enthusiasts are at play, clear, cool waters gently flow from reservoir to reservoir overrun with big money game fish.

|

|