Ten Days Later...

Without a doubt, the spring of 1970 was a tense and hot season for American college students. Protests and riots

flared up over the escalation of the war in Vietnam, the sending of US troops to Cambodia, the environment, civil

rights, and the inclusion of women into many formerly all-male universities and colleges. Certainly Kenyon College

was experiencing just such a difficult transitional period. At Jackson State University in Jackson, Mississippi,

tensions were particularly high in regards to racism and civil rights.

Since its establishment as a teacher's college in the late 1800s, Jackson State had been subject to racism. The

school moved from its original location because it was too close to an all-white area, and established a new campus

in an entirely black neighborhood. Lynch Street, named for Mississippi's first black congressman, bisected the

new campus and linked west Jackson, a white suburb, to the downtown area.

In the early 1960s, a Masonic Temple just down the block from the university on Lynch Street was the headquarters

for the Mississippi civil rights movement. Despite the proximity of the headquarters to the school, JSU students

participated little in demonstrations and protests. A state school, Jackson could not afford to alienate the all-white

board of education.

At nearby private institution Tougaloo College, students openly protested and organized sit ins, and brought a

march to Jackson State after being forced from a whites-only library. Instead of organized protests, JSU students

resorted to throwing rocks and bottles at white motorists who shouted racial slurs at them as they drove from their

downtown jobs to their suburban homes via Lynch Street.

Every spring, a mini-riot occurred at Lynch Street and the thoroughfare was temporarily closed, but the city still

refused to permanently reroute traffic despite numerous pleas from university officials.

In the spring of 1970, a popular female student was injured by a white motorist while attempting to cross Lynch

Street. White motorists already angered the student population by shouting racial slurs and epithets from their

windows while driving past campus, and students had retaliated by throwing rocks and bottles. With the already

mentioned national stress factors, and the death of four Kent State University students over a week earlier, Jackson

State students had enough to be worried about. Racism and the struggle for civil rights made their situation even

more unbearable.

A map of Jackson State University today.

What occurred at Jackson State University was a protest against racism. Unlike Kent State, students had not rallied

to protest the war in Vietnam.

On May 13, 1970, students amassed on Lynch Street but did not get out of hand. Governor John Bell Williams ordered

the Highway Patrol to establish order on the Jackson State campus, and students did not resist.

The next day, the President of the school twice met with students to listen to their concerns, but tension continued

to mount.

Around 9:30 PM on May 14, JSU students heard a rumor that Fayette, Mississippi mayor Charles Evers, brother of

murdered civil rights activist Medgar Evers, had been killed along with his wife. Students again gathered on Lynch

Street and began rioting.

The ROTC building was set on fire, a street light was broken, and a small bonfire was built, but the riot was still

a small one. Several white motorists called police to complain that students had thrown rocks at their passing

cars, but eyewitnesses later proved that it was non-students, known as "cornerboys," who did the rock

throwing. Firemen arrived to distinguish the fires, but requested police protection after students harassed them

as they worked.

Police arrived, blocked off Lynch Street, and cordoned off a thirty block area surrounding the University. Later

police told the media that they had received reports of gunfire for an hour and a half before arriving on campus.

On the west end of Lynch Street, National Guardsmen assembled, still on call for rioting of the night before. The

guardsmen had weapons but no ammunition.

There were seventy-five city police men and Mississippi State officers on the Lynch Street side of Stewart Hall,

a men's dormitory, to hold back the crowd as firemen extinguished a blaze. They were armed with carbines, submachine

guns, shotguns, service revolvers and some personal weapons.

When the firemen had departed, the police marched together, weapons in hand, down Lynch Street towards Alexander

Center, a women's dormitory, for reasons still unclear today. A crowd of 75 to 100 students massed together in

front of the officers at a distance of about 100 feet. There were reports that students shouted obscenities at

officers and threw bricks.

Someone either threw or dropped a bottle, and it broke on the pavement with a loud noise. Some say police then

advanced, while others insist the officers simply opened fire, or even others believe a campus security officer

had the students under control. At any rate, police began shooting, and later said they had been fired upon by

someone inside the Alexander West dormitory or that a powder flare had been spotted in the third floor stairwell

window. Two television news reporters agreed that a student had fired first, but were unsure as to where, while

a radio reported believed a hand holding a pistol had extended from a window in the women's dormitory.

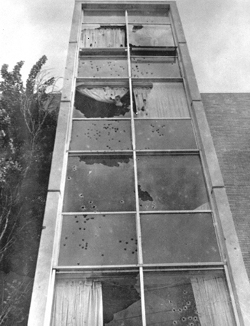

At 12:05 AM on May 15, then, police opened fire on Jackson State students and fired for approximately thirty seconds.

Students ran for cover, mostly inside one of the doors to Alexander West dormitory. Later police insisted that

they had only fired on the dorm, but today bullet holes can still be found in a building façade 180 degrees

across the street.

Struggling to get inside, students bottlenecked at the west end door of Alexander West. Some were trampled, while

others fell from buckshot pellets and bullets. They were either left on the grass or dragged inside.

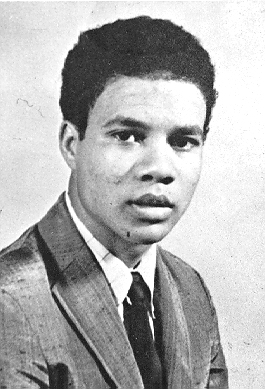

Fifty feet from the west end entrance to the dormitory, Phillip Lafayette Gibbs, age 21, lay dead from four gunshot

wounds: two in his head, one under his left eye, and one in his left armpit. Gibbs left behind a wife, one child,

and another on the way.

Phillip Lafeyette Gibbs |

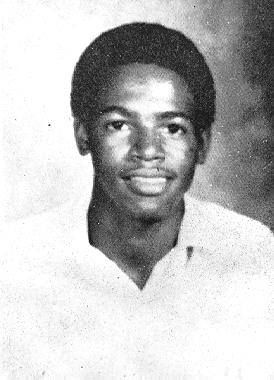

James Earl Green |

Each window facing the police in the five

story dormitory was shattered. At least 460 rounds were fired on the building, while investigators counted over

160 bullet holes on the outside of the stairwell alone.

Each window facing the police in the five

story dormitory was shattered. At least 460 rounds were fired on the building, while investigators counted over

160 bullet holes on the outside of the stairwell alone.  After the closing of Lynch Street, a plaza

was constructed. The Gibbs-Green Plaza, commonly referred to as "Plaza," is a multi-level brick and concrete

structure that blocks off J. R. Lynch Street and lies between Alexander Hall and the University Green. Students

often meet and spend time here in good weather. Jackson State frequently holds outdoor events on the Plaza, such

as dances, concerts, Greek shows, and Homecoming gatherings.

After the closing of Lynch Street, a plaza

was constructed. The Gibbs-Green Plaza, commonly referred to as "Plaza," is a multi-level brick and concrete

structure that blocks off J. R. Lynch Street and lies between Alexander Hall and the University Green. Students

often meet and spend time here in good weather. Jackson State frequently holds outdoor events on the Plaza, such

as dances, concerts, Greek shows, and Homecoming gatherings.

Just north of the Plaza is the Gibbs-Green

Monument, which stands outside of Alexander West dormitory.

In 1995, Demetrius Gibbs, son of Phillip Gibbs, received his degree from Jackson State. He says, "If I try

to tell people about the shootings at Jackson State, they don't know about it. They don't know until I say 'Kent

State.' For us to even be acknowledged, it had to happen at Kent State first."