|

|

Christian Religious Sites

| Cathedrals and Churches |

| The Merriam Webster online dictionary defines a pilgrimage as: a journey of a pilgrim, especially: one to a shrine or a sacred place. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia Online "Pilgrimages may be defined as journeys made to some place with the purpose of venerating it, or in order to ask there for supernatural aid, or to discharge some religious obligation." |  |

|

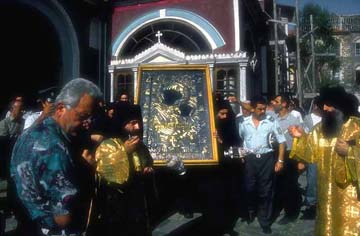

At right, Pilgrims seek Holy Water at the Monastery of Ivrion at Mount Athos |

copyright B. Mavridis may not be reproduced without permission |

|

The sites venerated by Christian pilgrims include sites of miraculous divine occurrences and/or appearances, famous cathedrals, and places made sacred by holy persons or martyrs: "Even after their [martyrs’] deaths, their tombs and the scenes of their martyrdom were considered to be capable also – if devoutly venerated – of removing the taints and penalties of sin" (Catholic Encyclopedia Online). In fact, this idea of pilgrimage as penitence came to be looked upon as a purifying act to visit the bodies of the saints and above all the places where Christ himself had set the supreme example of a teaching sealed with blood (Catholic Encyclopedia Online). Pilgrimage sites are thus sites of religious power. |

|

Procession of the Virgin Mary at the Monastery of Ivrion, Mount Athos |

Photo copyright of B. Mavridis May not be reproduced without permission |

The three most-visited Christian pilgrimage sites in Western Europe are Jerusalem, Rome, and the shrine of St. James at Compostela. Each site reflects a different sacred encounter. In Jerusalem pilgrims walk the route believed to have been traversed by Jesus (click here for a map of the route). As Mircea Eleade theorized, Christians there re-enacted and re-actualized the paradigmatic moments of Christianity.

Pope John Paul prays at the Basilica of the Savior in Jerusalem.

| In Rome pilgrims sought connection with the source of Catholic power in their contemporary world. This power is dramatically evident when pilgrims received papal indulgences during Jubilee years such as the year 2000. |

|

| Click here to take a virtual tour of St. Peter's in Rome. |

St. Peter's Basilica, Rome |

Jonathan Z. Smith theorizes another way of understanding the way in which pilgrimage sites come to be venerated. Rather than a site of a paradigmatic event, Smith believes that the establishment of shrines creates, rather than marks, a site of sacrality. For example, when the tomb of St. James (one of Jesus' apostles) was miraculously discovered in Compostela, Spain, it was believed that St. James' remains had been miraculously carried across the sea. The shrine built at Compostela became a major pilgrimage destination. The shrine was also important to the Christian Reconquest of Spain, because it established a Spain as a major Christian pilgrimage destination. Gothic cathedrals, before virtually unknown in Spain, were built along its route, bringing Spain into the cultural sphere of Europe rather than the Islamic world (take a virtual tour of one of the most popular Christian pilgrimage routes, the shrine of St. James, at The Road to Santiago). Pilgrimage routes directed the building of roads and contributed to Europeans' geographical sense of place.

The anthropologist Victor Turner has described how people in rites of passage are often marked by special clothing or tokens. The medieval pilgrim was easy to recognize, with penitential garb, perhaps a staff, and a sign purchased after reaching his/her destination.

Sandra Frankiel describes the difficulties faced by pilgrims; it could even serve as a punishment for sin. The following description of the recovered skeleton of a fifteenth-century pilgrim indicates the physical severity a pilgrim might have suffered:

More than 500 years after his death, the condition of the pilgrim’s remains . . . shows that a life of arduous walks left him severe arthritis in his legs, toes, spine, ribs, and pelvis. As well as causing him "considerable pain," this led to fusion of some bones of the spine, coccyx, ribs, and sternum that would have had a crippling effect, said Mr. Philip Barker, the consultant archeologist studying the skeleton. (The Skeletal Pilgrim).

Such adversity must be acknowledged when considering why Christians undertook a pilgrimage. In this light it is easy to see how a pilgrimage could be viewed as a punishment of sin, a solemn way to travel the world, and a way to connect with a source of Christian power.

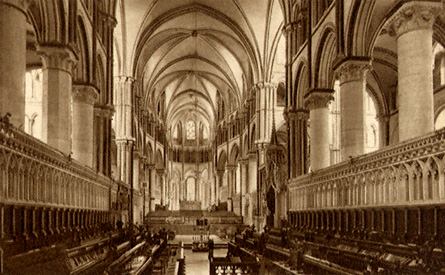

Pilgrimages are also made to famous cathedrals. Canterbury Cathedral is a good example of a cathedral that is both a site of local religious power (it is one of two archbishoprics in England), and also a shrine to the martyr Thomas Becket. Canterbury was the destination for Chaucer's pilgrims in The Canterbury Tales, and was believed to possess healing power through the virtue of Becket's blood. Vials of Becket's blood were sold as souvenir relics.

|

Canterbury Cathedral, England. |

History of Canterbury Cathedral

Established in 597 CE by St. Augustine who had been sent from Rome as a missionary by Pope Gregory the Great. Under the orders from the Pope, St. Augustine stayed in Canterbury and became its first Archbishop. Since 597, the Cathedral has been the primary ecclesiastical administrative center in England. It is widely considered the most beautiful cathedral within England. Architecturally it is wonderfully designed and the history surrounding this cathedral is unmatched. The Archbishop of Canterbury holds his seat there, which happens to be the most prominent religious position within England. Although an amazing work architecturally, the attention came to the cathedral after Thomas Becket was murdered by the King's knights in 1170. The number of pilgrimages that have been made to the Cathedral have actually worn down the steps at the front entrance of the building.

Canterbury Cathedral is the primary archbishopric in England. The power of the Archbishop in medieval times affected all of English society. Anytime an individual holds a high-ranking position within society, other people are attracted to their power. Many people are drawn to the Cathedral because the Archbishop of Canterbury resides there. As his place of work, it becomes powerful as well. Also, the Cathedral is old, beautiful and historic. Additionally, the power of Canterbury Cathedral is directly related to the murder of St. Thomas Becket. This powerful image of a historical event brings people from all over the world to Canterbury. The accessibility to both a Cathedral and a site of martyrdom enhances the power of the site. To this day, people may go see exactly where Becket perished. This accessibility allows individuals to form a unique bond with the site and provides a memory which stays with them for a long time. Because Canterbury Cathedral is both a church and the site of a historic event, it has established itself as an extremely powerful religious site within Catholicism.

The Grotto of Massabielle

A third example of a religious site is the grotto at Massabielle. The Grotto is a cavity in a rock where

in 1858 the Virgin Mary appeared to Bernadette Soubirous. Although it is

not a church it has became a place of worship. There is a stone marking the exact place in which Bernadette stood

when receiving these apparitions. Today, about five million pilgrims gather at the rock to experience this site

for themselves. At the left of the altar, the spring Bernadette discovered can be seen. It has produced 27,000

gallons of spring water each week since her visions. Some believe this water has healing power. Pilgrims are allowed

to drink from the spring and pray within the Grotto.

As with Canterbury Cathedral the power of the Grotto as a religious site stems from its pilgrims. The sites do differ in that one was the site of a gruesome murder and the other a heavenly apparition. Canterbury Cathedral is a beautifully designed and historic place of worship. The Grotto is a modest hole within a rock. Although physically opposite, symbolically they are remarkably similar. While Canterbury Cathedral continues as a functioning part of the Church, the Grotto is only a place of pilgrimage. Yet, people still manage to find their way to the Grotto, paying respects to the site where the Virgin Mary once appeared.

For pictures of the Grotto from the Lourdes website, click here.

Interestingly, it seems the importance of these religious sites within Catholicism serves a similar function as the Western Wall serves within Judaism. However, the Catholic sites differ because (with the exception of Jerusalem) they are directly tied to the saints with whose histories they are intertwined. Without one, the other would not exist as we know them. Their power originates from the saints associated with the site. Conversely, Catholics remember these saints because of the connection with the shrine. No matter what the circumstances, a martyrdom inside a Church or an apparition inside a cave still resonates power.

The shrines of martyrs were visited with increasing fervor in the fifth and sixth centuries, as places where new life and healing bubbled up for the faithful from the cold graves of the dead. (Peter Brown, 445)

Shrines of saints manifest the power of life over death, as both the Cathedral and the Grotto offer Catholics sites with healing powers. They focus divine power at a specific geographical location, accessible to believers. Pilgrims travel to a tangible place, where they can experience divinity for themselves, as well as a chance to experience the unique history of their religious institution. The image of Becket bleeding on the floor of the Cathedral seems more powerful then the image of Bernadette. Yet, Bernadette was a more holy individual. She directly spoke with Mary, while Becket was a martyr. Although the power comes from completely different situations, places and people, it is inherently equal. Both religious sites provide Catholics with a specific place to physically experience divinity. People may pray in the exact place where Bernadette spoke to Mary. This accessibility to divinity allows people to form a connection normally lacking within their lives, creating powerful experiences for those who seek a connection with the saints. Powerful in many ways, the most resounding effect of these sites is the impact they continue to have on observers and participants.

Bibliography

Brown, Peter. The Body and Society: Men, Women, and Sexual Renunciation in Early Christianity. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988.

Eliade, Mircea. Patterns in Comparative Religion. New York: World Publishing, 1963.

Smith, Jonathan Z. To Take Place: Towards Theory in Ritual. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Turner, Victor and Edith. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press, 1978.

Bernadette: at Catholic Saints Online

Mary: On Bernadette's Beatification at Catholic Encyclopedia Online