God Language and Feminist Christology

Must our image of God go? I shouldn't believe it strongly, but some sort of case could be made out. ~ C. S. Lewis

About Vertical Inclusive Language

| What is "vertical inclusive language?" "Vertical inclusive language" is language that equally reflects both male and female aspects of God; it is like inclusive language used to describe humans. Christian scripture and tradition has almost exclusively used masculine language, Father, Lord, King, He, despite the fact that Christian theology maintains that God has no gender. According to the theology, God's divinity contains the perfections of both the male and female. However, because God revealed God's self as male, Christianity has made masculine language normative in the description of God. Advocates of inclusive language argue that the use of masculine terms demonstrates and perpetuates patriarchy and sexism. Their solution would be the equal use of gendered terms. For example the use of Mother and She along with Father and He, and replacing of gendered terms with ungendered terms such as Parent and Monarch. Also, Jesus Christ could be called the Divine Child instead of Son of God. (Cooper 1) |

|

|

Eve and Adam image from Lycos Image Gallery and Pictures Now |

Some Variation Within the Movement

Evangelical Feminism: The movement holds that the biblical principle of equality requires women to have equal opportunity to that of men, to have positions in ministry, and within marriage to share authority and the power to make decisions. They do not believe that the Bible condones female subordination and spiritual superiority of males. They find the Bible to have an objective and authoritative meaning, a spiritual message that remains unchanged and obvious despite changing readers and interpreters of the text. Because of the equality of all of creation before God, evangelical feminists believe that there is no theological or moral justification for the subordination of any group or individual based solely on their race, gender or class. (Groothuis 1)

Theologically Liberal Feminism: This movement disagrees with evangelical Feminists; theologically liberal feminists argue that portions of the Bible in fact do teach female subordination. They view biblical interpretations and translations as contradicting the universal message of equality and therefore find the Bible to be authoritative but open to reinterpretation. The authority and meaning of the Bible is thought to lie not only in the text but also in "cultural preunderstandings," which theologically liberal feminists believe interpretation must take into account. For them, the reader determines authority or lack thereof of the text, as biblical meaning is found in the relationship between the reader and the text. The spiritual consciousness and feminism of women readers makes the Bible authoritative. (Groothuis 2)

Nonevangelical Feminist Theology: These movements argue for the subjectivity, relativity, and pluralism of religious truth. Groothuis charges that they view religion as a series of myths, metaphors and symbols, which together demonstrate religious truth. Groothuis believes that for nonevangelical feminists, religious truth is functional as personal belief, not substantial and universally true despite varying personal beliefs. (Groothuis 2)

Radical Feminist Theology: This theology holds that female spirituality is fundamentally different from male spirituality and therefore requires a different approach to the Bible. The female personification of Sophia (the wisdom of God) as more than a metaphor and the use of new interpretations of a radically feminist Bible do not separate sexuality from spirituality. (Groothuis 3)

History of the Movement

Evangelical Feminism emerged as a movement in the 19th century. The movement largely began in the work of abolitionists such as Sarah Grimke who, while trying to challenge slavery, found themselves needing to defend their right to speak out at all. In the 1830's Grimke and other evangelical leaders argued that the Bible had been incorrectly translated and interpreted. Tied to the argued belief of the time that the Bible fundamentally opposes slavery, was the notion that mistranslation makes the Bible seem to condone and make normative subordination of women. Groothuis states that Evangelical Feminism has not strayed far from the basic philosophy it began with nearly two hundred years ago. (Groothuis 2)

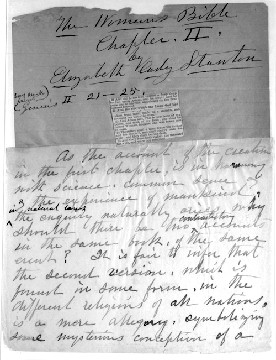

Elizabeth Cady Stanton edited The Woman's Bible in the late 19th century, shaping the theological liberal feminist movement. The Women's Bible is made up of sections of biblical text matched with reintepretation and commentary written by Stanton or other contributors.(San Francisco State University class project site) The contributors to the book argued that the Bible was contaminated with the sexism of the men who wrote it. Unlike Evangelical Feminists, Cady Stanton and her comrades believed that retranslating and interpretation would not fix this problem. They held that the Bible contains inherent androcentricsm. (Groothuis 2)

|

|

|

|

Sarah Moore Grimke image from National Women's History Month Page |

A page from The Women's Bible, edited by Elizabeth Cady Stanton image from San Francisco State University class project site |

Elizabeth Cady Stanton image from National Women's History Project |

The Debate over Gender Inclusive Language:

What are the bases for the argument to adopt "vertical inclusive language?"

Advocates of "vertical inclusive language" and feminist theology are found across ecumenical lines. There are Roman Catholics, Protestants and even a few conservative evangelicals and confessional communions. Besides arguing that "vertical inclusive language" will serve to overcome sexism, inclusivists employ scripture, tradition, hermeneutics, theology, and linguistics to justify inclusive language. Inclusivists who attest to the divine inspiration and ultimate authority of Scripture argue that within the Bible lies the foundation of "vertical inclusive language." They emphasize the portions of the Bible that are maternal or gender neutral (rock, fortress, light). The human character of the Scripture is also emphasized. While these inclusivists hold that the Scripture is divinely inspired, they argue that its language is culturally situated in the society of early Christianity and therefore not the final truth. The strong masculinity of God is an accommodation to the culture of the time, similar to God's accommodation of slavery and polygamy. Important figures who have used feminine language in reference to God are also invoked. These include Augustine, Chrysostom, Bonaventure, Julian of Norwich, and John Calvin. Inclusivists argue that if these important figures advocated inclusive language, it must be not simply a modern invention of feminist ideology. Rather, inclusivism must be consistent with biblical Christianity and history. (Cooper 2)

Some inclusivists separate the Word of God from biblical text. They argue that the text of the Bible was not inspired but was the recordings of encounters with God after the fact. They claim that the language of the Bible is completely human and therefore may be altered, when appropriate, in order to better express the religious truth that it was meant to communicate (Cooper 2). Inclusivists also cite Scriptural emphasis on divine justice and liberation. God revealed God's self to individuals, but also continues to be revealed in the modern church and its reading of Scripture. In this way the Bible can be seen as a revelation in progress. By reading Scripture themselves using inclusive language, women are part of a continuing revelation of God. Some inclusivists directly challenge masculine terms for God. A prime example is the allegation the Jesus might not have referred to God as Father, but Gospel writers made up that reference. (Cooper 3)

Using modern hermeneutics, and the notion that discussion about a text brings out the text's true meaning, inclusivists argue that humans' projections of meaning create a meaning for the text. This argument undermines the normativeness of masculine God language and justifies inclusive language. (Cooper 3)

" . . . finite knowledge and languages cannot encompass the infinite . . . metaphorical expressions, nonetheless, contain truth, and generally are authentic finite (obviously partial and limited) expressions of Reality. They may facilitate or distort the conceptualization of truth, but we should ever remember that the essence of personal revelation is an encounter with God in a personal relationship. Language is not the master, but the servant of revelation." ~ Meredith Sprunger (1)

| Theological doctrines such as divine transcendence and general or creational revelation are also invoked to support inclusive language. God can have no gender because God transcends all categories. They argue that attributing masculinity to God is a misunderstanding of the masculine terms used to describe God. In fact, some say that Christian tradition has made an idol of masculine language and worshipped a false God. Revelation doctrine holds that God's revelation is not exclusively textual and that creation is also a language and expression of God. Because of the creation of females in equal image and likeness of God, living women can be used as primary sources of God language. Also, God's transcendence makes any human label inadequate. Human definitions are thus anthropomorphic, symbolic, figurative, analogical, or metaphorical but never literal. Therefore masculine terms for God have no more accuracy than any other human word. The Bible contains both female and male metaphors, both of which, inclusivists argue, are equally valid in their equal inadequacy. (Cooper 3) |  |

|

Creation of Eve image from Lycos Image Gallery and Pictures Now |

A final argument is that God's name is not important. What God is and what God does are real and important. Inclusivists argue that inclusive language can express God's self and actions just as well as patriarchal linguistics. They argue that the essential meaning of the religion and theology will not change with inclusive language, except for the loss of sexism. (Cooper 3) Meredith Sprunger says, "The First Source and Center of all things and beings is not revealed by name but by nature. The name given this Ultimate Reality is of little spiritual importance"(1).

What are the arguments against "vertical inclusive language?"

We cannot eliminate fatherhood from the gospel without destroying its very meaning ~ W. A. Visser't Hooft (Sprunger 2)

| Mark Brumley explains an argument that defends the use of traditional, masculine language to describe God. Because God chose to portray himself as male, we as humans do not have the authority to manipulate his language to satisfy modern egalitarianism. While theologians could surely provide reasons why God chose to reveal himself in the way he did, and regardless of their persuasiveness, biblical witness remains the standard for addressing God and therefore must not be challenged. Challenging him and altering his self reference would replace the true God with one that we created. (Brumley 1) If the biblical witness of God's masculinity is dismissed, how can any of the claims of revelation be trusted? Brumley argues that abandoning the biblically emphasized masculinity of God, or to claim that masculine images of God have been humanly designed, rivals abandoning biblical revelation and thus Christianity itself. He believes that God has taught us how to refer to him. (Brumley 5) |

Still life with Bible image from Lycos Image Gallery and Pictures Now |

"loud insistence on a gender requirement for spiritual birth. If such a definition will harm anyone, it will surely harm women, by simplifying and demoting them to creatures of mere sexuality" (Groothuis 4)

The Bible never refers to God as having a sexual nature nor does it ever divinize sexuality. Creation possesses sexuality, not the creator. God is depicted in mostly masculine terms but Groothuis says this does not make God male. Existing biblical depictions of God as feminine would be unfit and not make sense if God were in fact male. The combination of God described in masculine and feminine terms shows that no sexual distinctions apply to God's nature. Carl Henry argues that the pronoun 'he' used in the Bible to refer to God is not a reference to his sexual gender, rather it is a generic pronoun that stresses his personality. (Groothuis 5)

While inclusivists may argue that the difference in masculine and feminine language is only quantitative (only about two dozen feminine references to God in contrast to tens of thousands of masculine references), Cooper argues that there are also qualitative differences that make a change to gender inclusive language inappropriate. He explains that all the feminine references are figures of speech whereas the masculine terms are titles, propernames and common nouns used to identify (appellatives), followed by Hebrew and Greek masculine grammar. He also points out that many of the feminine references are attributes coupled with masculine terms in the same sentence. For example,

"Of his own will he brought us forth by the word of truth that we should be a kind of first fruits of his creatures." ~ James 1:18

and,

"Hearken to me, O house of Jacob, all the remnant of the house of Israel, who have been borne by me from your birth, carried from the womb; even to your old age I am He, and to gray hairs I will carry you. I have made, and I will bear; I will carry and will save." ~ Isaiah 46:3-4

Therefore, Cooper argues that the Bible never refers to God as a female being, only as having feminine attributes. Cooper argues that the reduction of titles such as Father, Lord, and King to metaphors is a confusion. Cooper feels that equating the human terms such as Mother with the masculine divine titles undercuts the authority and determination which are integral to the process of naming. He sees God's names as not having meaning in their supposed representation of God, but in their historical context, their places in revelation. Mother does not share that history. (Cooper 5)

Along with the problem of gendering God, many women have had problems with the traditional representation of Christ as male.

Ruether's Liberation of Christology discusses the Christ symbol with regard to women:

"Christianity has never said that God was literally male, but it has assumed that God represents preeminently the qualities of rationality and sovereign power. Since men were assumed to be rational, and women less so or not at all, and men exercised the public power normally denied to women, the male metaphor was seen as appropriate for God, while female metaphors for God came to be regarded as inappropriate and "pagan". The Logos who reveals the "Father", therefore, was presumed to be properly represented even though the Jewish Wisdom tradition had used the female metaphor, Sophia, for this same idea. The maleness of the historical Jesus undoubtedly reinforced this preference for the male-identified metaphors, such as Logos and "Son of God", over the female metaphor of Sophia" (Ruether, 9).

Although Ruether views the Christ symbol as bounded in a sexist and male dominated symbolism, the question is still posed as to whether this Christ can be liberated from patriarchy. Ruether believes that in order to

"reaffirm the basic Christian belief that women are included in redemption, 'in Christ', all the symbolic underpinnings of Christology must be reinterpreted" (Ruether, 13).

However, is it possible to change the symbolism of the central figure of the Christian tradition when it is already so imbedded in the doctrine and rituals? For women like Ruether, a theologian and follower of the Catholic tradition, they are placed in a position of marginality because of the Christ symbol. However, if one is devout in a tradition she faces the decision whether to abandon the institution and start all over with new symbols and ideas or try to change the institution from within. Ruether believes that the Christ symbol can be re-interpreted through different means such as a new use of language (i.e. abandoning the Father-Son analogy), re-interpretation of Jesus' identity, and concentrating on Jesus as a "lived message and practice" rather than simply as a biological male (Ruether, 23). Ruether also points out that while the Christian tradition focuses on Jesus' maleness, they tend to forget his other human facets such as his position as a first century Galilean Jew. Through this new re-interpretation of Jesus' role and symbol, women will have more access to power. When Christology changes to incorporate women and put them on an equal plane, this equality transcends practice and rituals. Women will have become more powerful when the power symbol of the tradition, Jesus Christ, is more accessible and identifiable to them. Thus Christology and women would both be liberated from patriarchy.

Sexuality, Spirituality, and Feminist Religion by Rebecca Merrill Groothuis

Contemporary Theological Issues: Gender-Inclusive Language for God By John Cooper. Theological Forum Vol. XXVI, No. 3&4, December 1998

God Language By Meredith Sprunger. Spiritual Fellowship Journal, Fall 1993