|

|

The Eucharist

| The Eucharist has always been one of the most important aspects of Christianity. The Catechism of the Catholic Church strongly asserts the "Real Presence" of Jesus' body in the Eucharist; this is to say that the sacrament is not symbolic of the body and blood of Jesus but rather that it is his body and blood. This doctrine was affirmed at the Lateran Council of 1215. Additionally the Fourth Lateran Council confirmed the ancient Catholic teaching, that "no one but the priest [sacerdos], regularly ordained according to the keys of the Church, has the power of consecrating this sacrament" (Catholic Encyclopedia Online). The Catholic Church regards the Mass in which this ritual occurs as a sacrificial re-enactment of Christ's death on the cross, in which the priest "stands in" for Christ who is both high priest and sacrificial victim. Thus, the Mass is a substitute for animal sacrifices performed in the past. In the Catholic Church only males can become priests and perform this sacrifice. Therefore, because the Church states that reception of the Eucharist is necessary for Christian salvation, the laity's salvation is dependent upon sacrifices enacted by a male priesthood. |  |

|

A Priest Performs Mass |

|

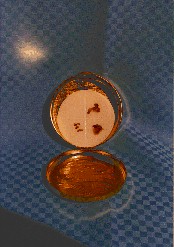

Starting in about 250 CE in the writings of Saint Cyprian, we begin to hear stories about hosts that bleed inexplicably and wine that turns into real human blood. Many of these miracles have been recognized by the church while some of the more recent miracles are still pending investigation. One of the most well-known of the Eucharistic miracles occurred when the Virgin Mary appeared to three chldren at Fatima in 1917. The Eucharist was of such great significance to Mary's message that the Virgin Mary's first apparition at Fatima took place on May 13, 1917, the Feast of Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament. At Fatima, a special prayer was given to the children which is believed to embody Mary's mission to restore the sacred and the holy. It reads: |

|

Bleeding Host in New Jersey, 1994 |

"0 Most Holy Trinity, I adore Thee! My God, My God, I love Thee In the Blessed Sacrament." |

Blood, Power, Gender and Eucharistic Miracles

As the Catholic church allows only males to be priests it is inevitable that the phenomenon of Eucharistic

miracles is gendered. Such miracles nearly always occur as the priest consecrates the host-- therefore they are

occurring at the hands of the male who is directly in charge of the church. Moreover, women are often the recipients

of the Eucharist experienced as miracle. Some of these miracles occur in a context of disbelief in the "real

presence" of Christ within the Eucharist. Are women the vessel by which to impress such faith to priests or

do the women themselves signify the "unbelievers"?

Miri Rubin claims that both statements have validity, that the role of women in these eucharistic miracles "exposes

the areas of sensitivity at the heart of a symbolic system." Rubin contends that the sacramental world view

contained in teachings about the Eucharist claims that "a miracle [has] become rule,", in that the Eucharistic

transformation becomes operative in every mass, every hour, at every place in the world where masses are celebrated.

Eucharistic miracles, in her view, are teaching tools for that world view, and thus, for the scholar, their

study exposes areas of conflict and tension within the symbolic system. Women were

both privileged receptors of such miracles, and suspicious on account of their lack of incorporation into the male

religious hierarchy: their position was . . . more precarious than has hitherto been recognized.

(Rubin, 114-121)

Protestant conceptions of the eucharist differ in one very important way from the Catholic conception of the sacrament: Catholics believe that through the words and actions of the priests transubstantiation occurs, and that the bread and wine that the priests hold become, in reality, the body and blood of Christ. At the time of the Protestant Reformation, these notions about the nature of the eucharist began to be contested. Most Protestant traditions call the ritual communion, rather than the Eucharist. There are major differences between the Protestant practice of communion and the Eucharist. Most Protestant traditions about communion do not rely on the power of a priest to transform the bread into the body of Christ. There are fewer rules governing the preparation and administration of communion. However it in no way makes this practice any less important to Protestant faiths.

It is necessary to understand that Protestantism is a general term encompassing many denominations and the practice of communion varies within these denominations. Some engage in the act of communion every Sunday, while others take part in it monthly, quarterly, or less. There are also differences in ideas about the nature of the consecrated bread and wine.

A common thread in Protestant conceptions of communion is that it does not require a priestly blessing to become significant. While an ordained clergy member is the ideal administrator, his or her words do not hold more power than the words of a layman. Rather, in their belief in the sacrament, Protestants bring forth their faith in Jesus and in God and the forgiveness of sins. It is more of a symbolic act commemorating the Last Supper, the Passion and its promised redemption.

Communion is one of two rituals practiced by Protestants; the other is baptism. While baptism is generally a one-time event, communion is to be repeated throughout the life of the believer (Gospel Out Reach). Both acts cleanse sins. The relationship between baptism and communion is quite strong. People must be baptized in order to participate in communion; they must also have made a confession of their faith. Depending on their denomination this confession may accompany baptism or come later. This means that communicants have confessed their belief in Jesus as the Christ who died and was resurrected for the forgiveness of their sins.

John Calvin, the founder of Presbyterianism, determined that the bread and wine were signs of the body and blood of Christ, but that there was in fact a real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. The Presbyterian conception of the eucharist is that it provides spiritual nourishment and growth in grace. By taking the bread and wine, the members have their union and communion with God and Jesus confirmed, and are also testifying their thankfulness to God and their love and fellowship with the rest of the congregation.

Transubstantiation:

Presbyterians see the concept of transubstantiation as absurd. That doctrine

which maintains a change of the substance of bread and wine, into the substance of Christ's body and blood by consecration

of a priest. . . is repugnant . . . overthroweth the nature of the Sacrament; and hath been, and is the cause of

manifold superstitions, yea of gross idolatries. (128).

State at Reception of Eucharist:

Not everyone should be allowed to receive the body and blood of Christ. Such

as are found to be ignorant or scandalous, notwithstanding their profession of the faith, and desire to come to

the Lord's Supper, may and ought to be kept from that Sacrament by the power which Christ hath left in his church…

(284). One must come without doubt and should ideally perform a set of actions and meditations during the

service. It is required of them that receive the Sacrament of the Lord's Supper, that, with all holy reverence

and attention they wait upon God in that ordinance, diligently observe the sacramental elements and actions…and

thereby stir up themselves to a vigorous exercise of their graces; in judging themselves and sorrowing for sin…

(286).

During the administration of the eucharist the priest is instructed to let the people know that it should not be

given to those who are ignorant or scandalous.

The Anglican Church and the Eucharist

Carey presides over opening Eucharist at

Lambeth Conference

Archbishop of Canterbury George Carey presided over 750 bishops at the Lambeth Conferences opening Eucharist

(Episcopal News Service photo by Jeff Sells/Anglican World)

http://ecusa.anglican.org/ens/photos.html

XXXVI. Of the Lord's Supper

The supper of the Lord is not only a sign of the love that Christians ought to have among themselves one to another;

but rather it is a Sacrament of our Redemption by Christ's death: insomuch that to such as rightly, worthily, and

with faith, receive the same, the Bread which we break is a partaking of the Body of Christ; and likewise the Cup

of Blessing is a partaking of the Blood of Christ.

Transubstantiation (or the change of the substance of Bread and Wine) in the Supper of the Lord, cannot be proved

by Holy Writ; but is repugnant to the plain words of Scripture, overthroweth the nature of a Sacrament and hath

given occasion to many superstitions.

The Body of Christ is given, taken, and eaten, in the Supper, only after a heavenly and spiritual manner. And the

mean whereby the Body of Christ is received and eaten in supper is Faith.

The Sacrament of the Lord's supper was not by Christ's ordinance reserved, carried about, lifted up or worshipped.

--- The Book of Common Prayer (of the Episcopal Church), "Historical Documents of the Church."

The Church Hymnal Corporation, New York:1979.

As shown in this official document, the Episcopalian church does not believe in transubstantiation, a major

tenet of the Catholic church. However, the Episcopal Church views the Eucharist as more than a commemorative ritual.

The Eucharist is seen as working also on a spiritual level: In receiving the consecrated

Bread and Wine of the sacrament of the Holy Communion, man's spirit is nourished and strengthened by the Body and

Blood of Christ.

In regards to the Eucharist, the Episcopal church also holds other beliefs:

Blood, Power, Gender, and Protestant Communion

Protestant conceptions of communion have greatly attentuated the connections between Jesus' sacrifice and the ritual commemorating it. Moreover, in most Protestant churches women can become ordained priests or ministers. However, it is noteworthy that as Protestantism has attenuated the sacrificial aspects of the communion ritual, it has instead greatly elevated the Christian notion of Jesus' sacrificial atonement (see Sacrifice in Christianity). Martin Luther claimed that humans could not save themselves, but were "justified" by their faith in Christ and his redeeming sacrifice. Most Protestant churches since have followed his lead and stress the absolute necessity for salvation of Jesus' death on the cross. Thus, images of blood and sacrifice have not disappeared from Protestantism, but are imagined in different ways than in the ritual of the Catholic Mass and Eucharist.

The Constitution of the Presbyterian Church. Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath-School Work. 1901.

The Encyclopedia of Religion and Philosophy.

Rubin, Miri. Corpus Christi: The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1991.

"Form for the Administration of the Lord's Supper."

"Theology And Practice Of The LORD'S SUPPER: A Report of the Commission on Theology and Church Relations of The Lutheran Church--Missouri Synod." Social Concerns Committee.

Communion (The Lord's Supper).

Information on the Episcopalian Church and the Eucharist