|

June 22, 2005 A War Shrine, for a Japan Seeking a Not Guilty VerdictBy NORIMITSU ONISHI

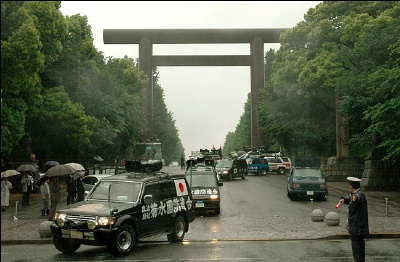

TOKYO - One recent rainy morning, a couple of dozen vehicles belonging to the Patriotic Youth League and other Japanese right-wing groups gathered inside the grounds of Yasukuni Shrine, the Shinto memorial to Japan's war dead. "Revere the Emperor," read a slogan on one truck. Others alluded to enemies unnamed: "Love and Protect our Motherland" and "Kill one, one at a time." At 12:30 p.m., the caravan spilled out onto Tokyo's streets, destination unclear. But the targets are usually the same: the Chinese Embassy, the liberal media, anybody daring to challenge the argument that Japan's wars were legitimate and that their leaders were not criminals. Yasukuni Shrine is the symbolic center of Japan's efforts to revise its militaristic past, and lies at the heart of worsening relations between Japan and its neighbors. Not only right-wing extremists, but now also mainstream politicians and the news media are more openly arguing that the 14 war criminals enshrined in Yasukuni were not guilty - and, because they were not, Japan's wars could not have been that bad. In a face-to-face meeting on June 20, for example, Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi steadfastly resisted the entreaties of President Roh Moo Hyun of South Korea that he stop visiting the shrine and build an alternate one that would be more acceptable to China and the Koreas, all of them victims of a brutal Japanese colonization. While the Japanese have received the bulk of the criticism for the shrine, they are not, however, the only ones to have manipulated the meaning of Yasukuni and its war criminals. So have the Chinese, the Taiwanese and the Americans, each according to their own interests. During America's six-year occupation of Japan after World War II, Americans spent the first half democratizing the country and prosecuting war criminals. In the second half, with Communists controlling China and the cold war bearing down, Washington reversed course: wartime leaders were rehabilitated overnight in an effort to make Japan strong. Some Class A war criminal suspects, after barely escaping the noose, became postwar Japan's political and business leaders; one, Nobusuke Kishi, even became prime minister. The mixed messages from America - as well as the highly politicized Tokyo Trials that tried the Japanese leaders but avoided mentioning Emperor Hirohito, whom America had decided not to depose - laid the seeds of confusion here. They also left open the door for the Japanese to argue that the overall verdict - that Japan had led a war of aggression - was also false. "It was a war of self-defense," Yuko Tojo, the granddaughter of the wartime prime minister who was executed as a Class A war criminal and is enshrined in Yasukuni, said in a telephone interview. "China claims it is unforgivable that the head of state visits Yasukuni, where those responsible for causing trouble by conducting a war of aggression are enshrined. But if we agree with China, it would mean that we recognize it as a war of aggression. So we can't." Visits to Yasukuni have long been regarded as coded endorsements of conservative nationalist views like hers. Indeed, when Mr. Koizumi said two weeks ago that he actually recognized the validity of the Tokyo Trials, the nation's largest-selling newspaper, Yomiuri Shimbun, which does not, was flabbergasted. "With what view of history has Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi visited Yasukuni Shrine in the past?" it asked in an editorial, adding that if Mr. Koizumi accepted the trials' rulings, "then Koizumi should not visit Yasukuni Shrine." Yasukuni Shrine was built in 1869, as part of Japan's drive to create a nationalistic state religion centered around a divine emperor. By the end of World War II, almost 2.5 million soldiers would be enshrined here for giving their lives for the emperor. Except for two civil conflicts, the other nine wars in which the soldiers died all revolved around Japan's advance into China, the Korean Peninsula, Taiwan and, ultimately, its attack on the United States. Yasukuni's war museum argues that America forced Japan into attacking Pearl Harbor as a way of shaking off the Depression, saying that "the U.S. economy made a complete recovery once the Americans entered the war." A video shown at the museum, called "We Won't Forget," describes America's postwar occupation of Japan as "pitiless." But the museum makes no mention of Japan's own occupation of Asia. As for the Rape of Nanjing, the museum blames the Chinese commander and adds that, thanks to Japanese actions, "inside the city, residents were once again able to live their lives in peace." In a written statement, Yasukuni officials said, "The exhibition is not based on any special historical viewpoint, but is based on clear evidence." Yasukuni's view of history is one that few Asians or Americans would accept. But like Japanese politicians, foreigners also appear to recognize the shrine's political value. Shu Ching Chiang, a Taiwanese lawmaker who is pro-independence and anti-China, visited Yasukuni in April. Taiwanese soldiers who served Japan's Imperial Army during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan are also enshrined in Yasukuni. "Every country has the right to pay respect to its war dead in the way it chooses," Mr. Shu said in a recent interview in Taipei. Like many Japanese, he compared Yasukuni to Arlington National Cemetery. Arthur Ding, an international relations expert at National Chengchi University in Taipei, decoded Mr. Shu's trip: "He delivered a message to Japan that his party wants a close relationship with Japan and to China that they are for Taiwanese independence." While the Chinese and the South Koreans have legitimate reasons to oppose the shrine, they have been accused of using it to shore up domestic support by appealing to nationalist sentiments. Noticeable in its silence on Yasukuni and the verdict on the Class A war criminals is the United States. As the nation that defeated Japan, occupied it and still has 50,000 troops deployed here, America is the one country that Japan may still listen to on these subjects. America is hardly a disinterested observer, after all, because Yasukuni deifies Japanese who ordered the attack on Pearl Harbor. American officials raise an eyebrow at Japanese comparisons of Yasukuni

to Arlington National Cemetery. But they tend to defend, albeit somewhat

uncomfortably, Japanese visits to Yasukuni, or maintain a studied silence.

The cold war may be over, but China's rise alarms America just as much

as did the rise of Communism in the 1940's. So better a strong, remilitarized

Japan, no matter what the Japanese say about Yasukuni or war criminals. |