August 12, 2001

Shrine Visit and a Textbook Weigh on Koizumi's Future

By HOWARD W. FRENCH

|

|

|

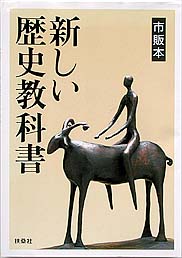

OKYO, Aug. 10 — Before Junichiro Koizumi can begin to enact his promised economic reforms, two actions will put their stamp on the rule of Japan's highly popular prime minister. Next Thursday, Japanese school districts will announce whether they are going to use a new, strongly nationalist history textbook at the junior high school level; Mr. Koizumi's government has just approved the book. On the same day, Mr. Koizumi is expected to decide whether to fulfill a campaign promise to visit Yasukuni Shrine, a Shinto monument to Japan's war dead that the country's leaders have avoided since 1985 because its history is so closely linked to emperor worship and militarism.

OKYO, Aug. 10 — Before Junichiro Koizumi can begin to enact his promised economic reforms, two actions will put their stamp on the rule of Japan's highly popular prime minister. Next Thursday, Japanese school districts will announce whether they are going to use a new, strongly nationalist history textbook at the junior high school level; Mr. Koizumi's government has just approved the book. On the same day, Mr. Koizumi is expected to decide whether to fulfill a campaign promise to visit Yasukuni Shrine, a Shinto monument to Japan's war dead that the country's leaders have avoided since 1985 because its history is so closely linked to emperor worship and militarism.

Mr. Koizumi has indicated that he may be wavering over the timing of his visit, since China and South Korea have warned that a visit would seriously damage Japan's gradually improving relations with them. Those warnings have been joined by increasingly powerful calls within Japan, including many in the ruling party, saying that a visit on Aug. 15, the anniversary of Japan's surrender in World War II, would be a mistake.

Although a full tally is not yet known, school districts seem to be shunning the new history book en masse, perhaps out of aversion to the opposition it has generated, including an arson attack late Wednesday on the offices of the historians' group that has been promoting it. Among other things, the textbook fails to mention that Japan invaded China in 1932, or that large-scale civilian massacres were conducted by the Japanese Army in Nanjing, China, and elsewhere, or that tens of thousands of women, particularly Koreans, were forced into sexual slavery for Japanese soldiers. The omissions caused the former South Korean foreign minister, Han Sung Joo, to write in a recent editorial: "The German question has been more or less settled. In Asia, however, Japan remains a difficult neighbor."

Eisuke Innami, leader of the Kokubunji Town school board, in Tochigi Prefecture, is one of those who has wrestled with the decision on whether to adopt the new textbook. "We asked each other, should we choose a textbook that has drawn so many criticisms from the neighboring countries," she said. "Even if we could protect our pride by selecting the book, if we come to be hated by our neighbors, there would be little meaning in protecting our pride."

Ms. Innami's sentiment seems likely to be a common one in the textbook decision-making process, and too in Mr. Koizumi's decision about visiting the shrine, which most commentators here have been treating as a crisis of his own making.

But what has been most remarkable in these days before Aug. 15 is the degree to which the nation has avoided vigorous discussion of its painful history. Consensus on the war's causes and the role of its leaders has eluded Japan. And its neighbors can never forget that the most common Japanese response to the atrocities committed by imperial troops is denial. "The occupation, the postwar era, the Showa era, the cold war and the 20th century ended without Japan clarifying the responsibility for its defeat, for starting the war and war responsibility itself," wrote Yoichi Funabashi, a columnist in the Asahi Shimbun this week. "We just drifted along, having lost our `ability to mourn.' The loss of the ability to mourn is one of the important phrases of Germany's postwar argument of history. Overcoming grief resulting from the loss of loved ones starts with squarely facing the hard facts and discerning its context and background."

Mr. Koizumi's comments about the war, like his about visiting Yasukuni Shrine, have been characteristically vague. In his very first news conference as prime minister, he said that Japan had waged war because it was "isolated from international society." Asked if Japan's colonial takeover of China and other countries had caused that isolation, he answered, "There are many different problems."

Likewise, Mr. Koizumi's government has limited itself to strictly procedural explanations of its approval of a history textbook that fails to mention the invasion of China. The education ministry has repeatedly said that its powers are limited to ensuring factual accuracy. And even when rejecting the new book, most of the 542 school boards across the country have strenuously avoided touching upon the nub of the controversy: its overt effort to sanitize Japan's past. "The good part of the new textbook was that it portrayed individual actors in Japanese history very well, and it gives a very good explanation of our culture," said Yasuhiro Yokoyama, one of the few board members anywhere who would describe his committee's deliberations. "The most common objection was that the terms and grammar are too difficult for today's children." "As for questions about its description of the war, it never came up," he said. "The government already approved the book, so we figure it is already satisfactory."

If many Japanese are not yet forthrightly confronting their history, the recent controversies have generated much discussion about the methods used to avoid a debate. Indeed, many point to kotonakareshugi, a word that means willfully ignoring troublesome things. "The basic line in this system is to acknowledge that there could be uncomfortable differences of opinions between you and others, and to simply accept the differences rather than debate them," said Toshiyuki Masamura, professor of social studies at Tohoku University. "Westerners wonder why Japanese people don't clarify their thoughts. But for Japanese, the overwhelming priority is the avoidance of confrontation."

Many Japanese intellectuals cite one overriding reason to substitute platitudes, procedural posturing and straightforward avoidance for a searching debate over the past, and that is the largely unexamined role of Emperor Hirohito in planning the war and allowing his deified persona to be used to rally the hordes of fallen soldiers enshrined at Yasukuni. "Problems like visits to Yasukuni Shrine and the textbook problem remain issues with us because we can't touch on the issue of the emperor," said Kaoru Takamura, a novelist whose writing sometimes uses allegory to examines historical themes. "It is easy to recognize that what Japan did to China and other Asian countries was aggression or invasion. But if we admit it, it inevitably comes down to the responsibility of the emperor for the war. And this has been shrouded in ambiguity by the way Japan was left at the end of the war." Ms. Takamura said that Japan would not be ready to face its past until the generation that fought the war has died.

Several important recent histories of the war and immediate postwar period in the United States have focused intensively on the emperor's responsibility in the war, and on Washington's role in shielding him from judgment. In his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, "Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan," Herbert P. Bix wrote that Hirohito's "own modus operandi as supreme commander, and the influence he exerted on operations, remain among the least studied of the major factors that contributed to Japan's ultimate defeat, and are therefore the most in need of reexamination."

But this observation has received little public attention in Japan, where newspapers hesitate to question the imperial role in the war out of fear of nationalist groups. Huge sound trucks circulate here every day, often parking near the offices of perceived critics of the emperor and blaring denunciations and militarist hymns at earsplitting volume.

"It may be too early to form a consensus about our history, but I would like to emphasize that it is not just waiting for the time to be ripe," said Kei Ushimura, a specialist in Japanese intellectual history at Meisei University. "Instead of being emotional, we must read documents, the raw materials of history, which can be obtained easily. People speak of the taboo surrounding the imperial system, but just like children who always find whatever their parents try to hide from them, nothing can conceal these records."