At its height, the Kaifeng community numbered as many as 5,000 Jews. Today, about 1,000 Chinese can trace their roots to them. Photo by Nir Keidar

Just when it seemed that he was about to sail through the Orthodox conversion oral exams with flying colors, Yage Wong found himself stumped.

“What blessing do we make on an eggroll?” a member of the rabbinical court asked the 27-year-old, who hails from a town near China’s Yellow River.

“What is an eggroll?” asked the perplexed young man, who today goes by the name Yaakov.

The rabbi headed toward the computer on his desk, googled the word "eggroll," and showed a picture of the tasty Asian appetizer to the aspiring convert.

“We don’t eat that where I come from,” said Yaakov. “It must be a Western food.”

Yaakov dreams of becoming the first rabbi to lead the Kaifeng Jewish community, a small Jewish community in China's Henan province, in more than 200 years. This week, he got one step closer to that goal. After immersing himself in the Hod Hasharon town mikveh, a ritual bath, and affirming his acceptance of the mitzvot, he was officially pronounced a Jew.

|

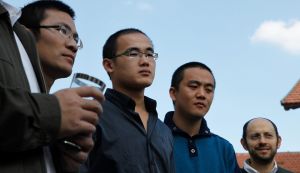

| Now that they have completed their studies, Yonatan and his friends plan to move to Jerusalem before joining the Israeli army. Photo by Nir Keida |

Yaakov was not alone. Five of his peers, all in their 20s, also participated in the conversion rituals, becoming the first group of men from this remote Jewish community to be accepted back into the fold after hundreds of years.

“It is the closing of a historical circle,” said Michael Freund, the director of Shavei Israel, a non-profit organization that reaches out to members of lost Jewish communities around the world, among them the Kaifeng Jews, and helps reconnect them with their roots.Yaakov and his friends are members of a small group of descendants of the Kaifeng Jews, who in recent years have expressed interest in exploring their religious roots and becoming full-fledged Jews. They were preceded in 2007 by a group of four Kaifeng women, who completed the conversion process in Israel.

“My grandparents always told us that we were descendants of the Jews,” said Yaakov, as he prepared to enter the mikveh. “We didn’t eat pork in our house, and we didn’t eat the blood from animals. I decided that I wanted to know more.”

The Jewish community of Kaifeng was formed roughly 1,000 years ago, when a group of Jewish merchants, presumably from Persia, settled in this region of China adjacent to the silk route. The Jews lived among themselves in a segregated community for hundreds of years before they began assimilating and intermarrying with local Chinese.

At its height, the community numbered as many as 5,000 Jews. Today, about 1,000 Chinese can trace their roots to them. Only a small fraction of that number, however, are active participants in the recently revived community.

In October 2009, Shavei Israel received permission from the Ministry of Interior to bring seven Kaifeng men to Israel so that they could explore the possibilities of conversion and aliyah. (The seventh member of the group was able to complete the conversion process several weeks ago, since unlike the others, he was already circumcised and therefore did not need to wait the extra time to recuperate.)

The Israeli rabbinate typically refrains from converting individuals who are not eligible for citizenship under the Law of Return – in other words, individuals who do not have at least one Jewish grandparent. Indeed, a request by another young member of the Kaifeng community, Wang Jiaxin , who arrived in Israel at about the same time as the current group, was rejected by the rabbinate.

Jiaxin subsequently underwent a Conservative conversion in the United States and then applied for Israeli citizenship under the Law of Return. Two months ago, his request was denied by the Ministry of Interior. The Ministry of Interior did not respond to a question about why his application had been rejected.

Last summer, however, a special exemptions committee did approve the conversion requests submitted by Yaakov, Shai, Yonatan, Moshe, Tzuri, Gideon and Hoshea – as they are known today – who have been studying for the past several years at Givat Hamivtar, a yeshiva in the Gush Etzion settlement of Efrat. Two months ago, they all passed their oral examinations at the rabbinical court, and six of them were subsequently circumcised.

And now, at long last, the big moment has arrived.

In typical Yeshiva-boy style, the young Chinese all have the tassels of their four-cornered tzitzit hanging out of their shirts as they enter the small building that houses the mikveh. An employee of the Hod Hasharon Religious Council hands them nail clippers and instructs them to clip both their fingernails and toenails. One by one, they are guided by three rabbinical judges to the ritual bath that lies behind a closed door. After they affirm their commitment to observe all the mitzvot, they are greeted with big hugs and cries of “mazal tov!” from their friends and teachers, who have come from the yeshiva to share this big day with them.

“I feel as if I have been reborn,” said 25-year-old Yonatan, formerly Xue Fei, who has just rushed out to call his friends in Efrat to inform them that he is now officially a member of the tribe.

Now that they have completed their studies, Yonatan and his friends plan to move to Jerusalem before joining the Israeli army. Yonatan, who practiced dentistry in China, says he then wants to become certified as an Israeli dentist. Tzuri wants to become a Jewish ritual slaughterer, and then perhaps open an authentic Chinese restaurant in Jerusalem.

Waiting for them on a small picnic table outside the mikveh are shots of whiskey in plastic cups. They raise their glasses in unison, but don't drink a sip until Tzuri recites the appropriate blessing, and Freund makes the following promise: “Our next job is to find you all nice Jewish woman.”