August 6, 1999

An Air of Reluctance in China's Crackdown on Falun Gong

By SETH FAISON

EIJING -- China's fierce-looking crackdown on Falun Gong, the spiritual movement that claims tens of millions of followers, is turning out to be far less severe than it first looked, with more propaganda than action. Although the authorities have detained tens of thousands of people and are spewing a deafening barrage of anti-Falun Gong publicity each day, ordinary offenders are being handled with relative leniency. Most of those detained are being released within a few days and sent home, apparently because officials at many levels of government fear the enormous disruption that would be caused by mass arrests for the innocuous crime of practicing a variant of an ancient form of meditation and exercise.

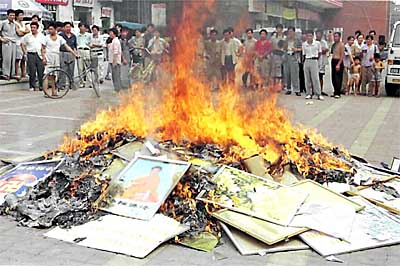

Books and other materials relating to the Falun Gong sect were set afire in the Chinese city of Shouguang on Wednesday. Though propaganda against the sect is intense, most followers detained are quickly released.

This deep contradiction -- the vehement pronouncements of the official campaign versus the more malleable reality -- points at both the resilience of the Communist Party's political apparatus and, paradoxically, the reluctance of the authorities to use it to its fullest extent. A harsh crackdown would also risk provoking an unpredictable backlash. In contrast to the severe punishment of participants in the 1989 pro-democracy movement, the authorities' hesitance to apply all their force against Falun Gong followers appears to reflect the shrinking status of the party in a society that has grown more disparate and hard to control over the last 10 years.Rather than retreating in fear, as the targets of previous political campaigns did, many Falun Gong practitioners are continuing to speak out against the crackdown as a misguided effort that will never shake their beliefs. Dozens of Falun Gong organizers remain in custody, and may face heavier charges. Many ordinary followers, however, say the authorities in their workplaces are deliberately fudging orders to check employees and obtain promises to stop practicing Falun Gong, in order to avoid the havoc of mass layoffs.

A 39-year-old schoolteacher surnamed Cao represents a new breed of political activist in 1999. She came to Beijing from her home in northern China on a personal mission to tell the nation's leaders about what she believes is the essential goodness of Falun Gong, which teaches its followers to adopt highly moral behavior and to think of others first. "No one can stop me from believing in Falun Gong," said Ms. Cao, a willful-seeming woman with short hair. "It changed my life. I will never stop practicing."

Ms. Cao tells a remarkable tale of her arrest, her quick release, rearrest and re-release in the days after the start of the crackdown last month. She came to Beijing on July 20 to protest the crackdown that Falun leaders heard was coming, and was one of hundreds of followers who were detained for protesting outside Zhongnanhai, the compound where China's top officials live and work. She was taken to a military post on the outskirts of the city.

Forced home on a military bus the next day, she immediately made her way back to Beijing, where she was arrested again at a sit-in in Tiananmen Square, the site of the 1989 student-led movement. Taken partway home again, Ms. Cao escaped the loose custody she was under and made her way to Beijing for a third time in a week. When she called home, she was told by her school's principal that she risked losing her job if she did not follow orders to return home. "I told him I don't care," Ms. Cao said. "They can take my job and my home. If I can't practice Falun Gong, there is no point in living."

This kind of defiance may seem remarkable in the face of the tough-talking Chinese authorities, yet it was echoed by seven other followers who were eager to tell their stories, and to communicate their determination to persuade China's leaders to rescind the ban on Falun Gong that was ordered on July 22. "We're not afraid of being arrested," said another schoolteacher, named Yang. "When we have contact with the government, that is when we can tell them what we think."

When this attitude is voiced by Falun Gong's organizers, it is not likely to be treated so kindly. The authorities have accused the movement's leaders of aiming to overthrow the government, a deeply serious offense, and have not publicized how many of the movement's top leaders have been detained or how their cases are being handled.

China placed a request through Interpol, the international police force, for the arrest of the movement's founder, Li Hongzhi, who is based in New York City. Interpol turned it down this week, citing a lack of criminal evidence. The State Department, meanwhile, has pointed out that the United States does not have an extradition treaty with China.

The lighter treatment of ordinary followers like Ms. Cao may reflect a tacit admission by the authorities that there is little wrong with practicing this form of qigong, the traditional exercises that the overwhelming majority of Chinese people believe can enhance vital energies. But the quick release of the people detained also seems to reflect concern by Communist Party officials that harsh punishment of Falun Gong followers could risk an unpredictable and dangerous backlash.

Political experts in Beijing say the anti-Falun Gong campaign is being directed by President Jiang Zemin. Jiang was apparently so disturbed by the lack of warning he received from security forces before more than 10,000 Falun Gong followers surrounded the Zhongnanhai leadership compound on April 25, that he ordered a far-reaching political campaign to force security and party officers into concerted action. Part of Jiang's intention may be to whip his forces into line in the run-up to Oct. 1, when China celebrates the 50th anniversary of the Communist state, a highly sensitive date that Jiang would like to cast as a grand observance of the party's glory with himself at the helm.

Ordinary Falun Gong followers say they reject official media reports demonizing Li, who founded the movement in 1992, and intend to continue to follow his teachings. "It has taught me to be a better person," said a coal company executive named Han, who said he was a Communist Party member. "They say we are a political organization, but I just bought the book and read it myself. Where is the organization there?" Han, like several other followers, said he did not mind losing his job if need be in order to continue practicing Falun Gong. "If you don't let me practice, I can't live," he said. "It would be like cutting my head off. How can I be a real person without it ?"

Despite the commitment that Han displays, he and other followers said they were not sure that they would actually lose their jobs for ignoring pleas from their leaders to stop protesting the crackdown. Yang said the principal of his school, situated 50 miles outside Beijing, was taking a typically ambiguous approach to orders to expel any employees who refuse to renounce Falun Gong. The principal, Yang said, did not want to lose all 20 teachers in the school who practice Falun Gong, so the principal asked others to forge confessions in the names of Yang and others, to be passed on to education officials as proof that the school was complying with the crackdown. Yang said a fellow Falun Gong believer who is a doctor had discovered that the director of his hospital had signed a fabricated confession in the doctor's name, to avoid the issue of whether the doctor would have to be let go.

A Chinese journalist who is not sympathetic to Falun Gong said he found the political campaign excessive and unnecessary, and argued that many of the confessions by Falun leaders broadcast by the authorities sounded so insincere that they seemed to be signaling a refusal to buckle. The journalist said he had been musing on the difference between the terror of the crackdown in 1989 and how silly the heavy-handed official statements seemed this time. "Marx was right when he wrote that history will repeat itself, the first time as tragedy and the second time as farce," the journalist said. "In 1989, it was a tragedy. This time it's a farce."