June 29, 1999

As Mystic Movement Assembles, Chinese Government Worries

By ELISABETH ROSENTHAL

EIJING -- Just after 6 a.m., they amble one by one onto the small plaza just outside Purple Bamboo Park, each depositing a seat cushion next to a decorative urn. They are a particularly motley crew: An easygoing middle-aged man in neat slacks and a windbreaker. A couple in their 20s, she with bright red lipstick and he with hennaed Elvis hair. A small old man in a Mao cap, lugging a stool.

It is hard to imagine that they have much in common as they gather in a half circle around a clean-cut young man in an immaculate blue track suit, with a matching gym bag. Then he pushes the button on a boom box that releases soft music and, in a smooth voice, takes the class through its exercises, with bits of Buddhist lore and cryptic commands: "Put palms together before you ... Move your fingers and palms in the cosmos ... Golden Monkey splitting its body ... Move the wheel to your stomach -- hold it as long as you can."

These are the newest adherents of Falun Gong, or Buddhist Law, the group that has melded Buddhism, meditation, Chinese exercise techniques, civics and the mystical ideas of its exiled founder, Li Hongzhi, into a wildly popular movement. The group has the government worried. For the last two months, China's leaders have been involved in a subtle battle of words and wills with the group -- ever since 10,000 Falun Gong members unexpectedly staged an extraordinary illegal sit-in around the leadership compound, demanding official tolerance and recognition for the beliefs.

Claiming tens of millions of ardent followers in China, Falun Gong has emerged as a powerful if hard-to-define force that the government must reckon with. The group has no obvious political agenda and claims only a loose organization. But the demonstration in April displayed its enormous power to move its members, and its capacity to embarrass the Communist Party if it does not get its way.

In recent weeks China's leadership has responded with a blitz of circulars, government meetings, newspapers editorials and even television broadcasts, trying to reassure members that they will be allowed to practice but at the same time to dampen enthusiasm for the group. The government sees Falun Gong as promoting superstition and as a threat to public order. Government circulars have advised officials to discourage party members from joining and instructed those who are already members to cut their ties. In recent days the official People's Daily has published a number of essays criticizing superstition, which do not specifically mention Falun Gong but pointedly warn, for example, that "some people claim that qigong is mysterious and can cure all diseases, but this is against scientific knowledge."

Falun Gong considers itself to be a branch of qigong, the traditional Chinese exercise and meditation technique, believed by many to have healing powers. But criticizing Falun Gong requires a delicate touch, since it pits the party against a huge number of ordinary people who are devoted adherents, including many retired functionaries.

At least one Communist Party elder and Falun Gong practitioner has written a letter to leaders defending the group. And recently, 13,742 members in Hebei Province signed an open letter to President Jiang Zemin demanding the legal publication of the group's books and protesting persecution of some members who had been briefly detained, the Hong Kong-based Information Center on Human Rights and Democracy in China reported.

Already, there have been a few quiet results of the government's campaign. For example, a small red bookstore here that did a booming business last month selling Falun Gong books and tapes is now shuttered with a sign saying, "Closed for Rectification."

But at Purple Bamboo Park and dozens of other public places in Beijing, crowds continue to flock to daily sessions, each displaying the mixture of qualities that makes Falun Gong somehow more than an exercise group and yet less than a religion. Practitioners refuse to talk to reporters, and coaches aggressively shoo away anyone with a camera, reinforcing the mystery. But the crowd in this park seems not so much defiant as oblivious to the government pressure -- going through their paces in full view of the police under a newly hung Falun Gong banner.

Here, every morning, there is a beginner class of a dozen or so outside the front gate, and a one-to-three-hour practice session of 100 to 200 people on a small plaza amid the leafy hills inside. Each session involves set exercises, followed by prolonged meditation. The crowd, which is mostly middle-aged and retired, thins considerably after 7:30 a.m., when a number put on their shoes and go to work.

At the beginners' class there is clearly more exercise than devotion, as retirees struggle good naturedly to get into lotus position and two assistants meticulously adjust the arm position of students trying a sweeping movement called "two dragons plunging into the sea." Many clearly seek not enlightenment but health. A 70-year-old former basketball player surnamed Zhang said he had started learning a month ago to help recover from a recent stroke. "My son suggested I try it, and I've made a little progress," he said. "Of course, I still take my medicine, but I think this will help."

Many Falun Gong practitioners rave about how the technique has cured chronic diseases from back pain to high blood pressure, and this has been a major selling point of the group. "Before I started this, I spent $125 a month at the hospital," said a 56-year-old woman surnamed Wang, smoothing her hair after meditation. "I was overweight and had high blood pressure and constant neck aches. In the last three years I haven't needed a doctor at all."

But critics say the group actively discourages medical care, causing some members to neglect serious illness. Other practitioners said they had been attracted by the way the group emphasized "good moral values," discouraging smoking and drinking, for example. For them the session clearly had the same rejuvenating quality that others might get from a massage or a good yoga class -- and they freely admitted that they were devoted to that high.

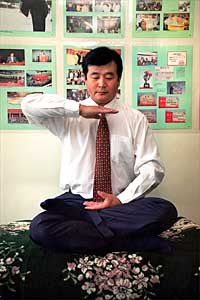

But it is hard to overlook the mysticism, which includes repeated references to obscure Buddhist deities and one long segment in which students move an imaginary "law wheel" around their bodies. The goal of Falun Gong is to get this wheel, with its purported healing powers, to take up residence in the abdomen.

Longtime adherents of Falun Gong bristle when it is called a religion or a cult, but it certainly has a few of the trappings. Still, many rank-and-file members, newly freed from headaches and colds, seem untroubled by the overtones or the ethereal debate. "I don't know if there's a wheel in the stomach," said Ms. Wang, who used to work in a radio factory. "All I know is that I feel better."