![]()

September 17, 2003

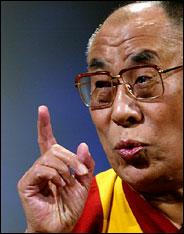

The Dalai Lama on Tour, an Exile on Main Street

By LAURIE GOODSTEIN and DANIEL J. WAKIN

| |

|

![]() n his 15th

trip to the United States, the Dalai Lama has been met by sold-out crowds

from coast to coast. Tickets to his events have been bid up on

n his 15th

trip to the United States, the Dalai Lama has been met by sold-out crowds

from coast to coast. Tickets to his events have been bid up on

As he begins the first of nine days of events in New York, this son of Tibetan peasants is at the high point of his global fame as a religious leader, head of state, pop icon, multimedia phenomenon and ascetic Buddhist superstar.

The Dalai Lama has always drawn a small circle of devotees in this country, but the huge turnouts on this trip are testimony to a growing American fascination with Buddhist practices and the search for genuine spiritual heroes who profess nonviolence in an era of religious strife and disillusionment.

"I think I'm looking for something; I don't know quite what," said Vivian de Mello, of Providence, R.I., who is Catholic. Ms. de Mello paid $60 for a ticket in Boston on Sunday in what she called her quest to find a new religion.

"He makes me feel good, and I need that right now," said Michelle Caron, a financial controller from Medford, Mass., as she descended the stadium stairs after the event. "Just his aura, and the simplicity."

The Dalai Lama's popularity also owes something to the presence of his

beatific visage on hundreds of books and videos, some which have recently

crossed over to the mainstream market from religious and New Age audiences.

One, "The Art of Happiness," sold more than 1.2 million copies and was

on The

There are more than 300 listings for Dalai Lama books on

"He is regarded as a religious voice, but he definitely crosses over into self-help," Ms. Garrett said.

As Tibet's leader in exile, the Dalai Lama is primarily concerned with pressing for Tibetan autonomy from Chinese rule. Some supporters say they worry that mass marketing of his image has diluted his message, but others say his celebrity status has only broadened the cause of Tibetan freedom as well as the appeal of Buddhism.

Among Tibetans and their supporters, the Dalai Lama's visibility is prompting some controversy, said Matthew Wiener, director of programming at the Interfaith Center of New York and its Buddhism analyst.

"That is a consistent internal debate and question about the more trendy the Dalai Lama gets, how does that affect cause of Tibetan freedom, and how does it affect the Buddhist message of compassion," Mr. Weiner said.

The Dalai Lama has lent his name to so many books and projects, said Yodon Thonden, executive director of the Isdell Foundation, which supports Tibetan causes, that "in some ways it dilutes the impact of his presence."

Nevertheless, Ms. Thonden said, his high profile is ultimately beneficial for the Tibetan cause.

The Dalai Lama gives permission to almost every request to use his name or likeness, many who know him say.

"He'll give a talk and someone will ask him if they can put it in a book, and he almost always says yes," said Amy B. Hertz, who as executive editor of Riverhead Books has published three recent Dalai Lama books, including "The Art of Happiness."

Mr. Wiener said the Dalai Lama had made a conscious decision to be highly public, partly motivated by a sense among Tibetans that their history of isolation left them vulnerable to the Chinese takeover.

"The reverse of that is to say, `Hey, we have to get publicity, we have to get the word out about our problems,' " Mr. Wiener said. "The Dalai Lama's extroverted response is in large part the result of thinking they got it wrong."

Advances and any profits from the books are usually divided between the authors and the Tibetan government-in-exile, Ms. Hertz said.

The Dalai Lama was born Lhamo Thondup to peasants in northeastern Tibet. At age 2, he was recognized as the reincarnation of the previous Dalai Lama and taken to the Tibetan capital, Lhasa, to be educated by Buddhist scholars and monks. He was enthroned in 1940, at the age of 5. Ten years later, China began its invasion of Tibet, and when China suppressed an uprising of Tibetans in 1959, the Dalai Lama fled to India. He has lived ever since in Dharamsala and has never been allowed by the Chinese to return to his native country.

His travels across the globe have helped him develop a mastery of the media event. At a news conference yesterday to start his visit in New York, he took the stage at an auditorium at the Guggenheim Museum, and, after a tempest of camera flashes, he asked the photographers to stop taking pictures. He peered leisurely into the audience and greeted familiar faces one by one. Then, with a broad smile, he told the photographers to return to work. "Well, yes, flash!"

Tickets for teaching sessions at the Beacon Theater in Manhattan have long since sold out — at $400 each, or $1,200 and $3,000 for V.I.P.'s and big donors. The steep prices are to defray the cost of advertising and producing the Dalai Lama's appearance this Sunday in Central Park, said Josh Baran, a publicist for the Dalai Lama's New York visit.

The Dalai Lama said recent contacts between Tibetans and Beijing were a "good start," and described a delicately balanced approach to China. He said he had always stressed that China should not be isolated and that issues of human rights, democracy and freedom should be raised in a "friendly atmosphere."

In recent years, China has poured money into Tibet and encouraged ethnic Chinese to settle there, bringing economic growth but also questions about the future of Tibetan culture.

"Unfortunately, sometimes our Chinese brothers and sisters need a little pressure," he said, adding: "And basically I feel pressure is not right. The friendly manner, the compassionate way, to educate them, explain to them and persuade them, that's the proper way."

He did not always draw such attention. The Dalai Lama first came to the United States in an era of widespread fear of new religions and dangerous cults.

Jeffrey Hopkins, a professor of Tibetan Buddhist studies at the University of Virginia who served as the Dalai Lama's interpreter from 1979 to 1989, said: "Twenty-five years ago, almost all the venues were small, people didn't know who he was, they had no idea where Tibet was, and they didn't know what religion to associate with him. They thought he might have been some far-out guru who maybe had selfish purposes."

But as his popularity has grown, some Buddhist leaders have expressed concern about what they call "bookstore Buddhists" who buy his latest releases and adopt Asian trappings without delving deeply into Buddhist teachings.

"We need to adopt the wisdom practice," said Surya Das, a widely known American lama, "not the Asian accouterments."