|

September 27, 2003 Was the Islam of Old Spain Truly Tolerant?

|

| |

|

![]() RANADA, Spain

— A dispenser of iced lemonade sits invitingly by the door of the newly

whitewashed building — hospitality for summer visitors coming to the

first mosque built in Granada in over 500 years.

RANADA, Spain

— A dispenser of iced lemonade sits invitingly by the door of the newly

whitewashed building — hospitality for summer visitors coming to the

first mosque built in Granada in over 500 years.

But looming over the freshly planted garden, seeming to quiver in the furnacelike heat, is another image: the Alhambra, a 14th-century Muslim fortress of red-tinted stone that is everything this mosque is not: ancient, battle-scarred, monumental. It seems at once a reminder of lost glories and a spur for their restoration.

It may also inspire darker sentiments. For it was from the Alhambra's watchtower that Christian conquerors unfurled their flag in 1492, marking the end of almost eight centuries of Islamic rule in Spain. Less than a decade later, forced conversions of Muslims began; by 1609, they were being expelled.

That lost Muslim kingdom — the southern region of Spain the Muslims called al-Andalus and is still called Andalusia — now looms over far more than the new mosque's garden. And variations of "the Moor's last sigh" — the sigh the final ruler of the Alhambra supposedly gave as he gazed backward — abound.

For radical Islamists, the key note is revenge: in one of Osama bin Laden's post-9/11 broadcasts, his deputy invoked "the tragedy of al-Andalus." For Spain, which is destroying Islamic terrorist cells while welcoming a growing Muslim minority (a little over 1 percent of Spain's 40 million citizens), the note yearned for is reconciliation.

The sighs have also included a retrospective utopianism. Islamic Spain has been hailed for its "convivencia" — its spirit of tolerance in which Jews, Christians and Muslims, created a premodern renaissance. Córdoba, in the 10th century, was a center of commerce and scholarship. Arabic was a conduit between classical knowledge and nascent Western science and philosophy. The ecumenical Andalusian spirit was even invoked at this summer's opening ceremony for the new mosque.

That heritage, though, can be difficult to define. Even at the mosque, the facade of liberality gave way: at its conference on "Islam in Europe," one speaker praised al-Andalus not for its openness but for its rigorous fundamentalism. Were similar views also part of the Andalusian past?

The impulse to idealize runs strong. If Andalusia really had been an enlightened society that combined religious belief with humanism and artistry, then it would provide an extraordinary model, offering proof of Islamic possibilities now eclipsed, while spurring new understandings of the West. In Spain, that idealized image has even been institutionalized. In Córdoba, a Moorish fortress houses the Museum of the Three Cultures. There was once a time, the audio narration says, when "East was not separated from West, nor was Muslim from Jew or Christian"; that time offers, it continues, an "eternal message more relevant today than ever before." In one room, statues that include the 12th-century Jewish sage Maimonides; his Islamic contemporary the Aristotelian Averroës; and the 13th-century Christian King Alfonso X are illuminated as voices recite their most congenial observations.

A more scholarly paean is offered in "The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain,"(Little, Brown, 2002) by Maria Rosa Menocal, a professor of Spanish and Portuguese at Yale University. Ms. Menocal argues that Andalusia's culture was "rooted in pluralism and shaped by religious tolerance," particularly in its prime — a period that lasted from the mid-eighth century until the fall of the Umayyad dynasty in 1031. It was undermined, she argues, by fundamentalism — Catholic and Islamic alike.

But as many scholars have argued, this image is distorted. Even the Umayyad dynasty, begun by Abd al-Rahman in 756, was far from enlightened. Issues of succession were often settled by force. One ruler murdered two sons and two brothers. Uprisings in 805 and 818 in Córdoba were answered with mass executions and the destruction of one of the city's suburbs. Wars were accompanied by plunder, kidnappings and ransom. Córdoba itself was finally sacked by Muslim Berbers in 1013, its epochal library destroyed.

Andalusian governance was also based on a religious tribal model. Christians and Jews, who shared Islam's Abrahamic past, had the status of dhimmis — alien minorities. They rose high but remained second-class citizens; one 11th-century legal text called them members of "the devil's party." They were subject to special taxes and, often, dress codes. Violence also erupted, including a massacre of thousands of Jews in Grenada in 1066 and the forced exile of many Christians in 1126.

In fact, throughout Andalusian history — under both Islam and Christianity — religious identity was obsessively scrutinized. There were terms for a Christian living under Arab rule (mozarab), a Muslim living under Christian rule (mudejar), a Christian who converted to Islam (muladi), a Jew who converted to Christianity (converso), a Jew who converted but remained a secret Jew (marrano) and a Muslim who converted to Christianity (morisco).

Even in the Umayyad 10th century, Islamic philosophers were persecuted and books burned. And despite the Córdoba museum's message, Maimonides and his family fled Muslim fundamentalism in Córdoba in 1148 when he was barely in his teens. Averroës was banished from Córdoba about 50 years later. Tolerance may have left less of a cultural mark than intolerance: the historian Joel L. Kraemer has suggested that in Andalusia, a sense of precariousness inspired mysticism, esoteric teachings and a "prudent dissimulation" before Islamic superiors.

And what of Andalusian cultural interchange? Ms. Menocal cites the ways Islamic styles appear in Spanish synagogues (one, in Toledo, even incorporating Koranic inscriptions) and in the 14th-century Christian palace the Real Alacazar in Seville. But far from exhibiting convivencia, these resemblances display the power of a culture as dominant as American popular culture is now: it is imitated even if otherwise opposed.

None of this, though, reduces the impulse to idealize Andalusia. One reason may be that it looks so good given what followed. In the 1391 pogroms in Christian Spain, for example, an estimated 100,000 Jews were killed, 100,000 converted and 100,000 forced to flee — a prelude to the 1492 expulsion of all Jews and the 17th-century expulsion of all Muslims. In comparison, many societies might resemble paradise.

But there was also something intrinsically astonishing about Andalusian culture. A visitor feels that instantly in its surviving buildings. They, too, invite idealization, but their power has little to do with notions of tolerance or liberality.

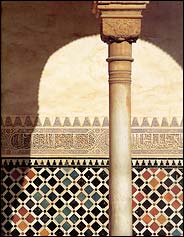

In the great mosque of Córdoba, for example, begun in the eighth century, the geometric effects are breathtaking. Cascading matrices of arched stone, which once framed thousands of worshippers, lead the eyes outward toward the ever-receding edges of perceptible space. Later Islamic styles retain that sense of enclosure and complexity: filigreed ornamentation surrounds arches and windows, shaping the inner world as much as framing the outer one.

But these varieties of Islamic style, far from reflecting a humanistic vision, suggest a world governed by the rigors of the intellect and the strictures of law. That world, whether in a mosque or a palace, presumes submission and declares mastery. It also seduces, for within its all-encompassing bounds, playful ornamentation and speculation take flight.

But the individual is not the focus of attention. The position or status of the individual is. This is quite different from the humane ideal so often attached to Andalusia's name. The outcome is not a version of tolerance, though at its best it can offer a version of the sublime. The viewer is absorbed in a formal world that overwhelms, inspiring awe with intricacies that seem beyond comprehension.

The Alhambra is a monument to the Andalusian sublime. It is a pillared paradise, calmed by the murmur of fountains. The throne room, dazzling with mosaics of sunlight and filigree, is crowned with a wooden model of the Islamic heavens.

But the Alhambra is hardly a model for contemporary aspirations. It does not frame the world; it divides it. It is both a fortress and a palace, thrusting a grim, forbidding face outward and an ornamented countenance inward. Its aggressive facade and precious interior are irreconcilable. It was the last Muslim redoubt in a Christian realm, an embodiment of the Moor's last sigh.

And when this monument to a culture's grand, expansive dreams and

its quest for reflective purity finally fell, the Christians understood

the message in their own way. In 1492, the year of its fall, Queen Isabella

and King Ferdinand triumphantly met in Alhambra's halls and there committed

themselves to both expansion and exorcism: they sent Columbus away on

his voyage and expelled the Jews from Spain. The resulting sighs and

satisfactions are still being sorted out.