|

June 15, 2004 8 Justices Block Effort to Pull Phrase in PledgeBy LINDA GREENHOUSE

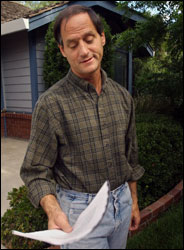

All eight justices who took part in the case agreed that the federal appeals court in California ruled incorrectly last year when it held, in a lawsuit brought against a local school district by the atheist father of a kindergarten student, that the reference to God turned the daily recitation of the pledge into a religious exercise that violated the separation of church and state. But in voting to overturn that decision, only three of the justices expressed a view on the merits of the case. With each providing a somewhat different analysis, Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor and Justice Clarence Thomas all said the pledge as revised by Congress exactly 50 years ago was constitutional. The law adding "under God" as an effort to distinguish the United States from "godless Communism" during the height of the cold war took effect on Flag Day - June 14 - 1954. The other five justices, in an opinion by Justice John Paul Stevens, said that the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit should not have decided the case because the plaintiff, Dr. Michael A. Newdow, lacked standing to bring it. While that procedural ruling left the constitutional issue unresolved, it did have the effect of removing a potentially inflammatory issue from the election-year agenda. Even if another plaintiff, one who has standing, challenges the pledge in a new case, there is virtually no chance that case could reach the Supreme Court before next year. Dr. Newdow and the child's mother, Sandra Banning, who were never married, live apart and under a California court's custody order, Ms. Banning has the final say over their daughter's education. Ms. Banning, a Christian, filed a brief with the Supreme Court expressing her desire that her daughter, who is now 10, continue to recite the pledge with "under God" in it. Referring to Dr. Newdow, Justice Stevens said that "the interests of this parent and this child are not parallel and, indeed, are potentially in conflict." He said that while Dr. Newdow was free to "instruct his daughter in his religious views," California law did not give him "a right to dictate to others what they may and may not say to his child respecting religion." Lacking a plaintiff with standing, the federal courts did not have jurisdiction over the case, Justice Stevens said. Justice Antonin Scalia recused himself last fall from the case, Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow, No. 02-1624, at Dr. Newdow's request after having publicly criticized the Ninth Circuit's ruling. In a telephone interview on Monday, Dr. Newdow, an emergency room physician who is also a lawyer, said he had heard from "fellow atheists who are waiting in the wings" to bring similar lawsuits of their own. How the next case might turn out is anyone's guess, he said, noting that "three justices said the pledge is O.K. and five didn't say anything." Dr. Newdow argued his own case before the Supreme Court with passion and flair. Asked in the interview whether that was the experience of a lifetime, he answered by expressing great frustration with the California family law. "The experience of a lifetime is to love your kid and be with her," he replied. The competing opinions on Monday were portraits in irony, some probably intentional and some, perhaps, not. Justice Stevens, one of the court's most liberal members, offered a paean to judicial restraint in explaining why the court should not reach the merits of the case. The "unelected, unrepresentative judiciary in our kind of government" should not reach out unnecessarily to decide cases, Justice Stevens said, quoting from an opinion written in 1983 by the conservative icon Robert H. Bork, then an appeals court judge. Justice Stevens is a consummate craftsman, and the sly reference was clearly intentional. Chief Justice Rehnquist, who like his fellow conservatives is usually inclined to a strict application of the court's rules on standing, this time criticized the majority's invocation of the doctrine as "novel," "ad hoc," and so narrowly drawn as "to be, like the proverbial excursion ticket - good for this day only." Whether the chief justice intended it, that remark mirrored almost exactly the criticism of the majority opinion he joined four years ago in Bush v. Gore, the case that decided the 2000 election through an unusual application of equal protection principles and with instructions that the decision not be cited as precedent for any other case. Addressing the merits of the pledge issue, Chief Justice Rehnquist said that "reciting the pledge, or listening to others recite it, is a patriotic exercise, not a religious one." In her opinion, Justice O'Connor called the pledge a permissible example of "ceremonial deism" rather than religious worship, similar, she said, to the words the Supreme Court's marshal intones at the start of each session: "God save the United States and this honorable court." While both Justice O'Connor and Chief Justice Rehnquist found the pledge constitutional under the Supreme Court's existing precedents, Justice Thomas took a different approach. The court's church-state precedents made the pledge unconstitutional and those precedents should be re-examined, he said. The issue of Dr. Newdow's standing had shadowed the case, and the outcome was not particularly surprising. The appeals court had ruled that while he did not have standing to sue on behalf of his daughter, he had the right to assert that he, as a parent, was injured by his daughter's exposure to a religious message that contradicted his own lack of belief. That analysis was erroneous, Justice Stevens said. Emphasizing Ms. Banning's "veto power" under state law, Justice Stevens said that Dr. Newdow could not use his status as a parent to go to court to "challenge the influences to which his daughter may be exposed in school when he and Banning disagree." He added, "When hard questions of domestic relations are sure to affect the outcome, the prudent course is for the federal court to stay its hand." |