![]()

June 11, 2004

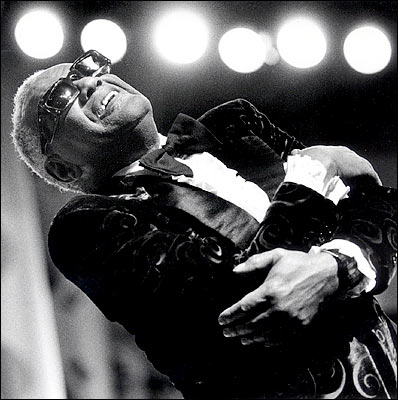

Ray Charles, Bluesy Essence of Soul, Is Dead at 73

By JON PARELES and BERNARD WEINRAUB

| |

|

![]() ay

Charles, the piano man with the bluesy voice who reshaped American music

for a half-century, bringing the essence of soul to country, jazz, rock,

standards and every other style of music he touched, died yesterday at

his home in Beverly Hills, Calif. He was 73.

ay

Charles, the piano man with the bluesy voice who reshaped American music

for a half-century, bringing the essence of soul to country, jazz, rock,

standards and every other style of music he touched, died yesterday at

his home in Beverly Hills, Calif. He was 73.

Mr. Charles underwent successful hip replacement surgery last year and had been scheduled to start a concert tour this month, but developed other ailments and died of complications of liver disease, said his publicity agent, Jerry Digney.

Mr. Charles brought his influence to bear as a performer, songwriter, bandleader and producer. Though blind since childhood, he was a remarkable pianist, at home with splashy barrelhouse playing and precisely understated swing. But his playing was inevitably overshadowed by his voice, a forthright baritone steeped in the blues, strong and impure and gloriously unpredictable.

He could belt like a blues shouter and croon like a pop singer, and he used the flaws and breaks in his voice to illuminate emotional paradoxes. Even in his early years he sounded like a voice of experience, someone who had seen all the hopes and follies of humanity.

Leaping into falsetto, stretching a word and then breaking it off with a laugh or a sob, slipping into an intimate whisper and then letting loose a whoop, Mr. Charles could sound suave or raw, brash or hesitant, joyful or desolate, insouciant or tearful, earthy or devout. He projected the primal exuberance of a field holler and the sophistication of a bebopper; he could conjure exaltation, sorrow and determination within a single phrase.

| |

|

In the 1950's Mr. Charles became an architect of soul music by bringing the fervor and dynamics of gospel to secular subjects. But he soon broke through any categories. By singing any song he prized — from "Hallelujah I Love Her So" to "I Can't Stop Loving You" to "Georgia on My Mind" to "America the Beautiful" — Mr. Charles claimed all of American music as his birthright. He made more than 60 albums, and his influence echoes through generations of rock and soul singers.

Joe Levy, the music editor of Rolling Stone, said, "The hit records he made for Atlantic in the mid-50's mapped out everything that would happen to rock 'n' roll and soul music in the years that followed."

"Ray Charles is the guy who combined the sacred and the secular, he combined gospel music and the blues," Mr. Levy continued, adding, "He's called a genius because no one could confine him to one genre. He wasn't just rhythm and blues. He was jazz as well. In the early 60's he turned himself into a country performer. Except for B. B. King, there's no other figure who's been as important or has endured so long."

In an interview with The New York Times earlier this year, after being sidelined by surgery for months, Mr. Charles reflected on his career and seemed eager to be in front of an audience again. "Yes, I'm going to keep touring, keep performing, it's in my blood," he said in a recording studio in Los Angeles. "I'm like Count Basie or Duke Ellington. Until the good Lord calls my number, that's what I'm going to do." Several weeks after that interview he canceled a March 2 appearance at Alice Tully Hall in Manhattan because of postsurgery discomfort. "I ain't going to live forever," he said during the recording studio interview. "I got enough sense to know that. I also know it's not a question of how long I live, but it's a question of how well I live."

He had recently recorded an album of duets with such performers as Norah Jones, B. B. King, Willie Nelson, Bonnie Raitt, Michael McDonald and James Taylor that was planned for an August release. A movie, tentatively titled "Unchain My Heart: The Ray Charles Story," starring Jamie Foxx and directed by Taylor Hackford, has been completed, but its producers say they are uncertain if it will be released this year or next.

Mr. Charles influenced singers as varied as Elvis Presley, Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder, Van Morrison and Billy Joel. But he started out being influenced by a very different singer, Nat King Cole. "When I started out I tried to imitate Nat Cole because I loved him so much," Mr. Charles said. "But then I woke up one morning and I said, `People tell me all the time that I sound like Nat Cole, but wait a minute, they don't even know my name.' As scared as I was — because I got jobs sounding like Nat Cole — I just said, `Well, I've got to change because nobody knows who I am.' And my Mom taught me one thing, `Be yourself, boy.' And that's the premise I went on."

Ray Charles Robinson was born on Sept. 23, 1930, in Albany, Ga., a small town, and grew up in an even smaller town, Greenville, Fla. When he was 5 he began losing his sight from an unknown ailment that may have been glaucoma. He became completely blind by the time he was 7. But he began to learn piano, at first from a local boogie-woogie pianist, Wylie Pitman; he also soaked up gospel music at the Shiloh Baptist Church and rural blues from musicians including Tampa Red.

He would say years later that racism in the South affected him just as it had any other black person. "What I never understood to this day, to this very day, was how white people could have black people cook for them, make their meals, but wouldn't let them sit at the table with them," he said. "How can you dislike someone so much and have them cook for you? Shoot, if I don't like someone you ain't cooking nothing for me, ever."

He attended the St. Augustine School for the Deaf and the Blind from 1937 to 1945. There he learned to repair radios and cars, and he started formal piano lessons. He learned to write music in Braille and played Chopin and Art Tatum; he also learned to play clarinet, alto saxophone, trumpet and organ. On the radio he listened to swing bands, country-and-western singers and gospel quartets. "My ears were sponges, soaked it all up," he told David Ritz, who collaborated on his 1978 autobiography, "Brother Ray."

Asked recently what effect blindness had had on his career, Mr. Charles replied: "Nothing, nothing, nothing. I was going to do what I was going to do anyway. I played music since I was 3. I could see then. I lost my sight when I was 7. So blindness didn't have anything to do with it. It didn't give me anything. And it didn't take nothing."

He left school at 15, after his mother died, and went to Jacksonville, Fla., to earn a living as a musician. He played where he could as a sideman or a solo act, taking jobs all over the state and calling himself Ray Charles to distinguish himself from the boxer Sugar Ray Robinson. He modeled himself on two urbane pianists and singers, not just Cole, but also Charles Brown, carefully copying their hits and imitating their inflections.

After three years, he put Florida far behind him and moved to Seattle. There he formed the McSon Trio, named after its guitarist, Gosady McGee, and the "son" from Robinson. He also started an addiction to heroin that lasted 17 years. Mr. Charles made his first single, "Confession Blues," in Seattle in 1949, credited to the Maxin (a different spelling of McSon) Trio. His second single, "Baby Let Me Hold Your Hand" by the Ray Charles Trio, was recorded in Los Angeles in 1950 with musicians who had played with Cole. The singles were hits on the "race records" (later rhythm-and-blues) charts, and Mr. Charles moved to Los Angeles.

He joined the band led by the blues guitarist Lowell Fulson, and became its musical director. After two years touring the United States, he left to resume his own career. In 1953 he signed to Atlantic Records; he also moved to New Orleans to work with Guitar Slim as pianist and arranger. Guitar Slim's "Things That I Used to Do," featuring Mr. Charles on piano, became a million-selling single in 1954, and that convinced Mr. Charles to abandon his imitative style and free his own voice. He moved to Dallas and formed a band featuring the Texas saxophonist David (Fathead) Newman. After working with studio bands on his first Atlantic singles, he convinced that label to let him record with his touring band, playing arrangements that had been road-tested on the rhythm-and-blues circuit.

"I've Got a Woman," recorded in a radio-station studio in Atlanta with his seven-piece band, became Mr. Charles's first national hit in 1955, starting a string of bluesy, gospel-charged hits, among them "A Fool for You," "Drown in My Own Tears" and "Hallelujah I Love Her So." In the mid-1950's he expanded his band to include the Raelettes, female backup singers who provided responses like a gospel choir, and they became a permanent part of his music. It was the beginning of the rock 'n' roll era, but Mr. Charles's songs were not geared to teenagers; they had the adult concerns of the blues. Nonetheless, his songs began showing up on the pop charts as well as on the rhythm-and-blues charts. At the same time Mr. Charles made clear his allegiance to jazz, recording an album with Milt Jackson of the Modern Jazz Quartet in 1958 and appearing at the Newport Jazz Festival.

In 1959 a late-night jam session turned into "What'd I Say." It was a blues with an electric-piano riff, a quasi-Latin beat and cheerful come-ons that gave way to wordless call-and-response moans. Although some radio stations banned it, it became a Top 10 pop hit and sold a million copies. But his next album, "The Genius of Ray Charles," took a different tack: half of it was recorded with a lush string orchestra, half with a big band. He also recorded his first country song, a version of Hank Snow's "I'm Movin' On."

Mr. Charles left Atlantic for ABC-Paramount Records in 1959 when it offered him higher royalties and ownership of his master recordings. He began to reach a larger pop audience with songs including two No. 1 hits, his version of "Georgia on My Mind" in 1960 (one of his first songs to win a Grammy) and "Hit the Road Jack" in 1961. With increasing royalties and touring fees, Mr. Charles expanded his group to become a big band.

By the early 1960's Mr. Charles had virtually given up writing his own material to follow his eclectic impulses as an interpreter. He made an instrumental jazz album, "Genius + Soul = Jazz," playing Hammond organ with a big band featuring Count Basie sidemen. On a duet album he made in 1961 with the jazz singer Betty Carter, two highly idiosyncratic voices sounded utterly compatible. And in 1962 he released the album "Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music," remaking country songs as big-band ballads. His version of "I Can't Stop Loving You" reached No. 1 and sold a million copies.

After recording "Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, Vol. 2," Mr. Charles settled into an office building and studio in Los Angeles that remained his headquarters ever since. He returned to rhythm and blues for his other major 1960's hits: "Busted" in 1963 and "Let's Go Get Stoned" in 1966. But he was also recording standards, country songs and show tunes.

In 1965 Mr. Charles was arrested for possession of heroin. He spent time in a California sanatorium to shake his addiction and stopped performing for a year, the only break during his long career. When he emerged he resumed his old schedule: touring for up to 10 months with the big band and releasing an album or two every year. He started his own label, Tangerine, which released albums through ABC and on its own. In the mid-1970's he started another label, Crossover, which released albums through Atlantic.

His presence on the pop charts had dwindled, but he was still widely respected. In 1971 he joined Aretha Franklin for the concert she recorded as "Aretha Live at Fillmore West." His version of Stevie Wonder's "Living for the City" won a Grammy in 1975. His autobiography became a best seller in 1978. In 1979 his version of "Georgia on My Mind" was named the official state song of Georgia, and in 1980 he appeared in the movie "The Blues Brothers."

During the 1980's Mr. Charles returned to the charts, this time in the country category. The boundary-crossing Southern music he had envisioned with "Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music" had been not just accepted, but treated as natural. He signed to CBS Records's Nashville division and made "Friendship," an album of duets with 10 country stars, which included songs with George Jones and Willie Nelson that reached the country Top 10 in 1983. He sang "America the Beautiful" at the Republican National Convention in 1984.

In 1986 Mr. Charles was one of the first musicians inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He received a Grammy for Lifetime Achievement in 1987, and in 1989 he appeared on Quincy Jones's album "Back on the Block," winning another Grammy in 1990 for a vocal duet with Chaka Khan on "I'll Be Good to You." All in all he won a dozen Grammys for his recordings, as well as the achievement award. Also in 1990 he turned up in television ads for Diet Pepsi, singing, "You got the right one, baby, uh-huh!"

Mr. Charles's private life was complicated. He was divorced twice, and leaves behind 12 children, 20 grandchildren and 5 great-grandchildren. Among his numerous awards were the Presidential Medal for the Arts, in 1993, and the Kennedy Center Honors in 1986.

In the interview earlier this year, Mr. Charles said that, having aged, he could sing only music that moved him in a way that he could not quite define. "I guess I'm kind of a strange animal," he said. "What works for me is songs that I can put myself into. It has nothing to do with the song. Maybe it's a great song. But there's got to be something in that song for me."

Asked if most of his songs were not suffused with sadness, he shrugged and said: "To be honest with you, I sing what I feel, what I genuinely feel. That's it. No airs."

Drivin' That Dynaflow

By VERLYN KLINKENBORG

| |

|

![]() id-60's

popular radio was a welter of youthful voices, just as it is now. But

every now and then a disc jockey would work Ray Charles, who died on Thursday,

into the rotation, and it was like hearing directly from Father Time.

I could never figure it out. The voice was so adult, so yearning and playful,

so self-contradictory — reedy and smooth, high-pitched and grumbling at

the same time. By then, a song like "What'd I Say (Part I)" was already

an oldie, recorded in 1959 when Ray Charles was (still? already?) in his

late 20's. And yet it sounded like more of a rave-up than even the early

Yardbirds could muster.

id-60's

popular radio was a welter of youthful voices, just as it is now. But

every now and then a disc jockey would work Ray Charles, who died on Thursday,

into the rotation, and it was like hearing directly from Father Time.

I could never figure it out. The voice was so adult, so yearning and playful,

so self-contradictory — reedy and smooth, high-pitched and grumbling at

the same time. By then, a song like "What'd I Say (Part I)" was already

an oldie, recorded in 1959 when Ray Charles was (still? already?) in his

late 20's. And yet it sounded like more of a rave-up than even the early

Yardbirds could muster.

The beauty of teen pop is that it believes that love belongs only to the very young. Maybe so, but with one vocal phrase Ray Charles could make it plain that real need — the real complexity of sexual passion — comes with age. He was singing many of the same words as the bands I listened to, but he meant something entirely different. Even his piano said so. I don't know what I would have done as a kid if I'd heard a song like "Greenbacks," about the dire economy of love, or "It Should've Been Me," that ode to sexual envy. Songs like that were far too grown-up for young ears, far too full of the blues.

Ray Charles made every kind of American music his own, and he repaid every kind of American music with his keen attention. You could hear the country and the city in his songs. You could hear Los Angeles and Dallas, New York and Seattle, the dirt roads of Georgia and Florida, the rundown brick facades of a hundred neighborhoods.

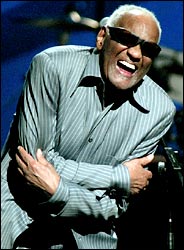

Watching him play — the rigid swaying of his body, the tight stuttering percussion of his hands on the keyboard — was enough to convince you that no one would ever get to the bottom of what he knew about his art. He would never be able to explain it. He would just have to play his way through the whole catalog of American music, and we would get to listen to him reinvent it, song by song.

June 14, 2004

OP-ED COLUMNIST

Loving Ray Charles

By BOB HERBERT

![]() ing

the song, children . . .

ing

the song, children . . .

In the summer of 1962, when John Kennedy was president, Ed Sullivan was the C.E.O. of Sunday-night television and the word Beatles still sounded to most Americans like a reference to insects, the airwaves were all but overwhelmed by Ray Charles's soaring country ballad "I Can't Stop Loving You." It was an amazingly popular song. But it was almost a hit by, of all people, Tab Hunter, not Ray Charles. That's right, Tab Hunter, a champion ice skater and one of the blandest pop stars it's possible to imagine.

Charles recorded the song first, on the now-legendary album "Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music." But neither he nor the executives at ABC-Paramount Records, which put out the album, expected the song to be a hit. For one thing, an earlier version by Don Gibson had gone nowhere. But disc jockeys started playing it, people loved it and Tab Hunter pounced. He put out a single that copied the Ray Charles album version almost note for note.

ABC had to scramble to put out its own single. In his book "Ray Charles: Man and Music," Michael Lydon described ABC's frantic effort to shorten the album version and get it distributed as a single. He quoted the arranger Sid Feller: "If Tab Hunter's record had gotten any more head start, Ray's record would have been lost. Even though Hunter was copying us, people would have thought we were copying him." Once Ray's single was available, said Feller, "Tab Hunter was finished."

I was in a taxi in Boston last Thursday, heading to Logan Airport, when I heard on the radio that Ray Charles had died. For someone who had grown up with his music, as I had, who had gyrated to it in moments of fierce adolescent ecstasy, and listened to it with the volume turned low on some of those nights that no one should have to go through, it was like hearing about the death of a close friend who was both amazingly generous and remarkably wise.

Even as youngsters in the late-50's and 60's, my friends and I knew that Ray was special. He had a shamanistic quality. We understood that his music, like life, was both spiritual and profane. And we reveled in the fact that it was also unquestionably subversive.

"I Got a Woman," which debuted in the Eisenhower era and remained a force in the popular-music culture for years, had an irresistible gospel feeling that moved with tremendous power toward a culmination that couldn't be anything but sexual. Whether he intended to or not, Ray had opened fire on two very distinct cultures at one and the same time: the white-bread mass culture that was on its guard against sexuality of any kind (and especially the black kind), and the black religious community, which felt that gospel was the Lord's music, and thus should be off-limits to the wild secular shenanigans that Ray represented.

But here's the thing. Ray Charles's music has touched so many people so deeply for so many decades precisely because it is religious. Listen to the way he transforms "America the Beautiful" from an anthem to a hymn. Listen to the joyous call-and-response of "What'd I Say?" or the slow majestic lament of "Drown in My Own Tears."

Ray's music envelops the willing listener in a glorious ritualistic expression of the sweet and bitter mysteries of life without the coercion, hypocrisy or intolerance that is so frequently a part of organized religion. It transcends cultures. It transcends genres — gospel, rhythm and blues, jazz, rock 'n' roll, country, pop. At its best, it is raw and beautiful and accessible, a gift from an artist who bravely explored regions of the heart and soul that are important to all of us.

Comparing himself to the early rock 'n' rollers, Ray said, "My stuff was more adult, filled with more despair than anything you'd associate with rock 'n' roll." Maybe that's why so many people were surprised to hear last week that he was only 73. In the obituary in Friday's Times, Jon Pareles and Bernard Weinraub wrote, "Even in his early years he sounded like a voice of experience, someone who had seen all the hopes and follies of humanity."

My friends and I all felt we knew him. He seemed as familiar as someone who'd actually hung out with us. An old friend. And it's hard whenever an old friend slips away.

Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company