DUNHUANG STUDIES - CAVE ART AND GALLERY

by Prof. Ning Qiang

Connecticut College

Main Themes of Dunhuang Art

Dunhuang art consists of three major forms: painting, sculpture and architecture. The inner space of a cave frequently imitates the interior design of residential or religious buildings. However, the shape of a cave must have been designed according to the function of the cave. Most Dunhuang caves were used as places for religious practice and political expression. Patrons of the caves demonstrated their social status, economic power, religious feeling, and political ideology by determining the size of a cave and by choosing certain motifs to be depicted in the cave. Therefore, we must be aware that religious themes represented in the Dunhuang caves may consist varied meanings, including social, political and personal ideas.

Buddhist Icons

Buddhist icons are the main theme represented in the Dunhuang caves. These icons include 5 basic

categories: the Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Arhans (Buddha's disciples), Heavenly Kings, and Protective

Warriors. They are often sculpted in large scale and placed in the western niches of the caves

as holy icons for worship. They are also painted on the walls as part of the entire design of

the murals.

A special type of icons, the "Auspicious Icons," should also be included in this section. The "Auspicious Icons" represent existing "images" of the Buddhas or Bodhisattvas. Unlike most Buddhist sutras and images of the Buddha, these "Auspicious Images" did not necessarily originate in India. Most of them were created and used by local Buddhist communities in various regions. These images, therefore, represent the ideas and tastes of local people and imply strong contemporary socio-political meanings in the regional/ historical contexts.

[Picture missing:]

Buddhist Stories

Many Buddhist stories are depicted in the Dunhuang caves. These stories can be divided into

four types: Jataka Stories, Hetupratyaya Stories, Sakyamuni's Biography and Buddhist Historical

Stories.

Jataka Stories describe the previous life of the Buddha when he was a deer, a king, a prince, a lion or a hare. The Buddha's virtuous activities explain his final achievement and set up a model for his believers.

Hetupratyaya Stories focus on the relationship between "cause" and "effect." Varied narratives are used to convey the same religious/ philosophical idea that there must be a "cause" behind an "effect."

Sakyamuni's Biography tells the whole story of the Buddha's life, from his birth to his death. More than eighty episodes of the Buddha's life can be seen in the Dunhuang murals.

Buddhist Historical Stories concentrate on important events took place in the history of Buddhism. Prominent monks, pious emperors, devoted lay believers, and miraculous Buddhist events are recorded in Buddhist historical texts and depicted in the Dunhuang paintings.

[Picture missing:] Subjugation of the Demons (Episode from the Buddha's biography). Painting on the northern wall of Cave 428. Northern Zhou Period (557-580). Photo by DRA.)

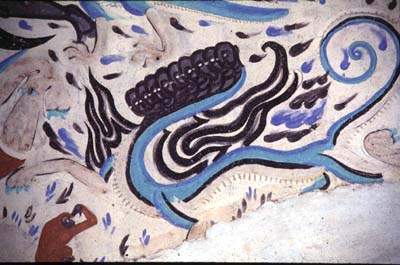

Daoist Deities and Mythological Figures

Traditional Chinese motifs of deities have also been identified among the figures depicted in the Dunhuang murals. Daoist deities such as the King Father of the East, Queen Mother of the West, and the winged immortals are represented with Buddhist motifs. Mythological figures including Fuxi and Nuwa are also displayed among the Buddhist-Daoist images. These multi-religious motifs reflect the inclusive and eclectic nature of the Dunhuang caves and the divergent composition of the local society.

Illustrations of Buddhist Sutras

Some Dunhuang murals represent Buddhist sutras (scriptures). They are commonly called "Jingbian"

(Sutra-illustrations). Most Tang-Song (618-1035 AD) Dunhuang caves depict varied Buddhist sutras

in large scale instead of choosing certain stories from the sutras, as we frequently see in

the early caves. Literary transformations of Buddhist sutras have also been illustrated in the

Dunhuang paintings.

Portraits of Donors

From the very beginning, patrons of the Dunhuang caves were portrayed in the caves they sponsored.

Those who sponsored the construction of the caves include varied classes of the society: local

rulers and foreign merchants, soldiers and officials, farmers and craftsmen, scholars and prostitutes.

Numerous donors can still be seen on the murals of the 492 caves remaining today. During the

early periods (366-580 AD), the portraits of donors are very small, with simple identifications

of their names and pure religious wishes. After the Sui Dynasty (581-618 AD), patron-images

gradually became larger and larger. Since the late Tang period (848-906 AD), most portraits

of donors became larger than Buddhist icons, reflecting the self-glorification of the patrons

in their caves.

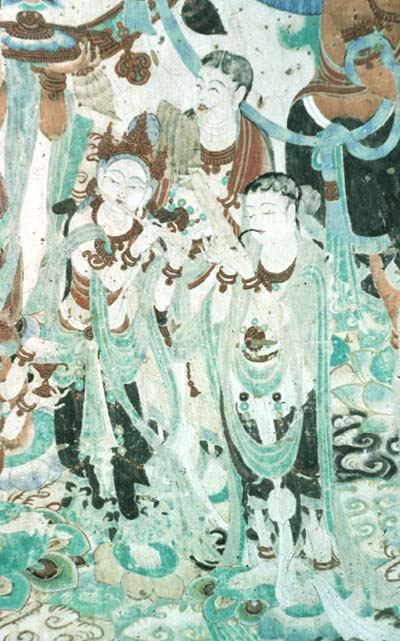

Apsaras and Musical Goddesses

Apsaras are the most popular heavenly beings in the Dunhuang caves. They play music or throw

flowers in the sky when the Buddha gives sermon to believers. In ancient Buddhist texts, they

were named Kinnara and Gandharva. They are now commonly called Feitian (Flying Beings) in Chinese

literature.

Musical Goddesses are depicted in the scenes of paradise. They play both Chinese and foreign instruments.

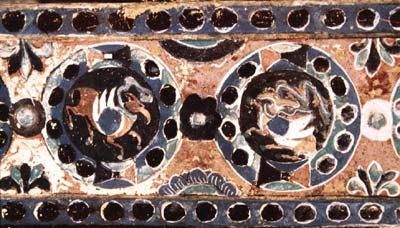

Decorative Patterns

Floral, animal and other patterns have been used to decorate the inner surfaces of the cave

at Dunhuang. They are unusually depicted on the ceiling or the borders of different pictures.

Although their main function is ornamental, most patterns have their own symbolic meanings.

For example, lotus lower symbolizes purity and the Buddhist law while the Baoxiang Flower (a

combination of peony and other lowers) stands for majesty and beauty.