The Environmental Crisis and Permaculture:

"The harmonious integration of landscape and people"

"Centuries were needed to know a part of the laws

of nature. A day is enough for the wise man

to know the duties of man."

--- Voltaire

An Introduction to the Environmental Crisis

Industrial-capitalist society exists under a fragmented, utilitarian world view. The roots of this world view

are based in the tenets of the European enlightenment, described in the philosophies of Descartes and Newton..

Both of these philosophers stimulated a shift in thought that through the centuries has become irrevocably incorporated

into the modern conception of reality. As Morris Berman states, we do not mean to assume that Descartes and Newton

were the only intellects involved in this shift, nonetheless their ideologies encompass many important facets of

modern life. Most significantly, the relationship between humanity and the environment has followed the patterns

of what we, as Berman, will call "the Cartesian paradigm" (Berman 24).

The "Cartesian paradigm" is defined by a control of nature. Descartes, in his Discourse on Method, lays

the logical foundation for this control:

[My discoveries] have satisfied me that it is possible to reach knowledge that will be of much utility in this

life . . . knowing the nature and behavior of fire, water, air, stars, the heavens, and all other bodies which

surround us . . . we can employ these entities for all the purposes for which they are suited, and so make ourselves

masters and possessors of nature. (Berman 25)

In the modern context, both governments and corporations regard natural resources as available strictly for economic

and technical needs in the form of capital. For instance, the army corps of engineers, through the construction

of dams or dikes, alter the natural flow of waterways and natural energy cycles for the development of human expansion,

in the form of power sources and agriculture. As the natural energy cycles are disrupted, both the interconnected

geographic and ecological elements of a specific landscape are permanently harmed. In the corporate sector, similar

examples can be found. Many corporations enforce practices of short term-high yield agricultural and resource exploitation.

Not only does this fit within the confines of the Cartesian dialectic of domination and mechanistic control, but

these practices represent the pinnacle of utilitarian achievement.

Carolyn Merchant explains, in regards to the Cartesian paradigm, that knowledge and understanding of being are

inherently connected into the structures of machines and that the presuppositions of this paradigm lead analogously

to another element of the machine — "the possibility of controlling and dominating nature" (228). Following

this to its extreme, Merchant concludes that seventeenth century corpuscular and atomic theories process reality

into parts, like the parts of machines that are "dead, passive, and inert" (229). Thus, modern rationality

within the Cartesian paradigm has demystified nature through this fragmentation and process of control. We believe

that this paradigm is the essence of the environmental crisis. Analyzing this crisis in single issues becomes a

futile attempt to "change the world" because the present situation necessitates a change in world view

and not merely a slight adjustment of consumer or corporate practices.

Nonetheless the situation is not as scary as it seems. To best understand a world view shift, or what a paradigm

is, the concept of incommensurability comes into play. A paradigm or world view is a conception of the reality

of the inward self and the external world. Such understandings, according to Thomas Kuhn, are based on current

values, needs and tastes of a certain time period. Such characteristics are manifested through the definitions

and standards used within that specific time period. Because of this, we can not compare or place judgment and

merit on one paradigm over another. The stark differences between paradigms leads us to Kuhn's concept of incommersurablity,

and thus to relativity of science ( Kuhn148). Aristotle is no better than Eienstein and 20th century industrial

capitalism is not the height of intellectual, social and scientific development. Yet this disruption of the recent

world view should not be feared or avoided. We should embrace our current state of economic and ecological crises

as crucial "turning point" period of change and renewal. Fritjof Capra emphasizes the importance of the

period of change as "not to be opposed but on the contrary, welcomed as the only escape from agony, collapse,

or mummification." ( Capra 33). Such changes have occurred in many pervious cycles of human history, marking

our change as not super-ordinary. This transition is of a planetary dimensions, effecting individuals, society,

civilization and ecology. As stated in the book I Ching, " The movement is natural, arising spontaneously.

For this reason the transformation of the old becomes easy. The old is a discarded and the new is introduced. Both

measures accord with the time; therefore no harm results" (34). .

Permaculture --- a viable alternative

Due to the inefficiencies and structural problems of our current understanding of nature and its relationship

to human society, we must look to new methods of existence. The philosophy and methodology of permaculture presents

humans with a viable solution to our current state. Permaculture (Permanent Agriculture) as defined and popularized

by Bill Mollison, is the

conscious design and maintenance of agriculturally productive ecosystems which have the diversity, stability,

and resilience of natural ecosystems. It is the harmonious integration of landscapes and people providing their

food, energy, shelter, and other material and non-material needs in a sustainable way (Mollison, ix).

However, the implications of permaculture are much more extensive. By embracing permaculture, humanity undergoes

a complete restructuring centered around new values of social community, food production and consumption. Our modern,

post-enlightenment conception of the natural world is transcended through the incorporation of an organic, ecologically

interconnected paradigm. The permaculture paradigm is based on the idea of emulating physical patterns of nature.

Permaculture recognizes the cyclical character of energy storage within the global ecosystem.. Living organisms

flourish not as individuals but as elements in a flow, not as masters but as life sustaining components of a greater

system (Bell, 63).

Permaculture, according to Mollison, is founded upon three ethical beliefs. In the absence of any universal moral

guidelines regarding the environment in the modern world, this alternative approach provides a compelling correlation

between ethics and the welfare of the environment. The constructs that Mollison suggests seem obvious, nonetheless,

they are often disregarded or misinterpreted in the industrial capitalist world. The three ethical guidelines are

a follows:

1. Care of the Earth: Provision for all life systems to continue and multiply.

2. Care of People: Provision for people to access those resources necessary to their existence. 3. Setting Limits

to Population and Consumption: By governing our own needs we can set resources aside to further the above principles.

(Mollison 2)

From each of these principles flows innumerable ethical applications, but the foundation remains the same.

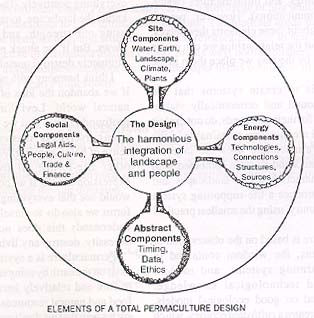

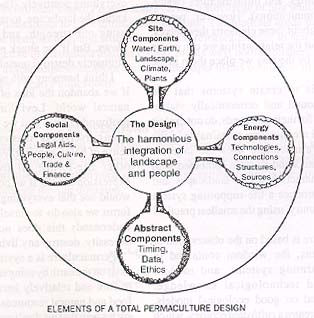

Permaculture is a growing phenomenon. Many horticulturists and home gardeners are exploring the uses of permaculture

in their daily lives. The viability of this practice within the modern world is promising because although it requires

a paradigm shift, the elements of our modern world view are not discarded. Rather, with the fundamental change,

elements of the economy, technology, and science can still be employed, albeit in different means. This can bee

seen in the figure to the right from Mollison's book Introduction to Permaculture. Each of the separate and equal

categories link together to create the "harmonious integration of landscape and people" (2).

These basic beliefs can be incorporated into many different styles of permaculture. In fact, every permaculture

garden is going to be specific to the exact location in which it operates. Likewise, there are many different philosophies,

such as those of Masanobu Fukuoka, Graham Bell, and Robert Hart, regarding permaculture, although the basic tenets

remain the same.

Masanobu Fukuoka--Reuniting Man and Nature

Through Natural Farming

In Masanobu Fukuoka's book One Straw Revolution the issues of man's separation

from nature and the failures of modern agriculture serve as the foundation for his arguement supporting natural

farming. Although Fukuoka is not by Mollison's definition a permaculturist, he incorporated many of the ethical

foundations of permaculture into his farming. By utilizing the natural tendencies of plants and the functioning

food chain, Fukuoka created a farm which produced more than industrial farms while replenishing the soil's vitality

(168).

As a former scientist, the role of science in agriculture is a predominant theme in his writing. Fukuoka believed

that science has proven that humans understand little about the true workings of nature. In his words, "The

irony is that science has served only to show how small human knowledge is" (29). By this he means that we

attempt to define and categorize all of the particulars in nature without seeing the whole picture. Many times

he describes researchers visiting his fields to ponder how his gardens produce so much without any of the modern

machinery and chemicals. In one such scene Fukuoka sets out one of the major problems with the scientific perspective

on nature:

This professor often comes to my field, digs down a few feet to check the soil, brings students along to measure

the angle of sunlight and shade and whatnot, and takes plant specimens back to the lab for analysis. I often ask

him "When you go back, are you going to try non-cultivation, direct seeding?" He laughingly answers,

"No I'll leave the applications to you. I'm going to stick to research" (75).

The problem is that there is a disjunction between what is done in the lab with what is done in the fields. But

there is also a problem with what the scientist sees in the fields. In an attempt to better understand the natural

relationships and workings within an agricultural system, the specialists see only what they are knowledgeable

in. As Fukuoka explains "Specialists in various fields gather together and observe a stalk of rice. The insect

disease specialist sees only insect damage, the specialist in plant nutrition considers only the plant's vigor.

This is unavoidable as things are now" (26). Science serves to move agriculture and people away from nature,

which he calls the "unmoving and unchanging center of agricultural development" (20).

The role of a farmer, in Fukuoka's mind, is an observer, not an intervener, of the natural order in his/her particular

landscape. Knowledge of the ecosystem does not come overnight and it does not come from books. Rather, he/she must

try to observe the changing nature of the ecosystem so that nature may cope with the obstacles of farming. Some

of the strategies that Fukuoka explains are the laying down of rice straw instead of compost, direct seeding to

retain the nutrients in the soil, sowi ng

clover to combat weeds, maintaining a healthy balance of predators and prey, etc (33-52). To do these things a

farmer must be in touch with the distinct natural system in his area. However, Fukuoka lays out what he calls the

"four principles of natural farming" as guidelines for any one who wants to try to create a natural garden.

These are :

ng

clover to combat weeds, maintaining a healthy balance of predators and prey, etc (33-52). To do these things a

farmer must be in touch with the distinct natural system in his area. However, Fukuoka lays out what he calls the

"four principles of natural farming" as guidelines for any one who wants to try to create a natural garden.

These are :

1. No cultivation. This means no plowing or turning the soil. The earth cultivates itself naturally.

2. No chemical fertilizer or prepared compost. These practices drain the soil of its natural nutrients and

increase human interference in the natural cycle.

3.No weeding by tillage or herbicides. Weeds are an important part of building soil fertility and in balancing

the biological community. As a fundamental principle weeds should be controlled, not eliminated.

4.No dependence on chemicals. Weak plants develop from such unnatural practices which increases their vulnerability

to disease and insects (33-34).

These are the practical foundations of natural farming. In and of themselves they are revolutionary with regard

to modern farming. However, he also believes that the environmental problem will not be solved until humans change

their entire view of nature. In the area of consumption, people need to reunite themselves with the natural way

of eating. He states that people "have lost their clear instinct and consequently have become unable to gather

and enjoy the seven herbs of spring (watercress, shepherd's purse, wild turnip, cottonweed, chickweed, wild radish,

and bee nettle). They go out seeking a variety of flavors. Their diet becomes disordered, the gap between likes

and dislikes widens, and their instinct becomes more and more bewildered" (136). Fukuoka argues for what he

called the "non-discriminating diet" this means that we leave all notions of human knowledge about food

behind and let nature provide for us. He said that there can be no rules or proportions for this diet because it

"defines itself according to the local environment, and the various needs and the body constitution of each

person" (143). In order for farmers to go back to the natural process of food cultivation, consumers need

to return to the natural flavors and textures of the earth. We need to stop, as Fukuoka says, "eating with

our minds" (137).

The separation between humans and nature has more heavy consequences than a poor diet. Fukuoka maintains that if

we do not see the error in our ways soon, human society will crumble. It is his view that "culture always

originates in the partnership of man and nature. When the union of human society and nature is realized, culture

takes shape of itself...Something born from human pride and the quest for pleasure can not be considered true culture.

True culture is born within nature and is simple, humble, and pure. Lacking true culture, humanity will perish"(138).

If this is true, humans will need to realize that we can not survive using the current system of monoculture and

lust for the perfect looking, chemical-dependent food.

Environmentally, Fukuoka points to our separation from nature as the origin of the current crisis. The more we

separate ourselves from nature, the more obscure the solution becomes. He talks about the reactionary tendencies

of modern environmental organizations and how this is a failure to see the entire problem. If Earth First fights

to save a section of old growth forest, it is "no matter how commendable, not moving towards a genuine solution

if it is carried out solely as a reaction to the overdevelopment of the present age"(21). These specific environmental

problems are symptoms of the larger problem of the disjunction between man and nature. To fight the symptoms does

not cope with the problem itself. Until, "the consciousness of everyone is fundamentally transformed, pollution

will not cease" (82). The farmer needs to "first be a philosopher. They should consider what the human

goal is, what it is that humanity should create" (74). The solution lies in a shift of world view which incorporates

the human as an integral part in the larger system of nature.

Fukuoka presents an economically sound, low impact agricultural practice as a method for dealing with our distance

from nature. All of the horrible symptoms which are caused when humans leave nature to try to control it would

be cured if everyone prescribed to the natural way of agriculture and living. In the perfect state, according to

Fukuoka, everyone would farm according to the tenets of natural farming. The land being divided up equally, everyone

could produce enough to live on. If the people were practicing natural farming, this would leave plenty of time

for family, community and leisure time. According to Fukuoka, "this is the most direct path toward making

this country a happy, pleasant land" (109). Fukuoka has given us a new system to work with which is economical

for the farmer as well as sustainable for our environment.

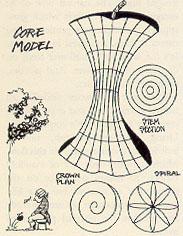

Graham Bell and the Practical Way

Graham Bell states that Permaculture is not a technique, but a mind-set and world view. Permaculture exists within

how things are placed together. In order to place natural components together properly, the patterns of the earth

need to be recognized. A recognition of quite logical and simple relationships of phenomena, yet crucial towards

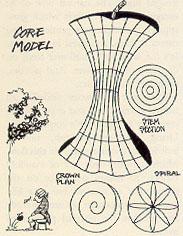

efficient and sustainable food production. Core Model is a template representing natural shapes. One may a understand

the Core Model by slicing an apple core from top to bottom. At one angle you can see concentric circles, at another

angle you see a parabola, at another angle you see spirals ( Bell, 63). Such shapes represent the forms of objects,

energy and fluid movement. By working with these shapes and incorporating them into your growing plan, you can

maximize productivity and lessen impact on the environment while increasing yield and plant health.

The Wind and Water pattern is an important fundamental in which to incorporate into the planning of growing sites.

The Macro-movement of Wind and Water is described best through climates and weather zones. Climate and weather

are variant, depending on the position on land. If you are growing in-land, you should expect colder winters and

hotter summers. If you grow along the ocean, climate changes are more moderate between hot and cold. Rotation of

the earth effects the wind course specific to hemisphere, Northern hemisphere( South -westerly winds), Southern

Hemisphere (North-easterly winds), in addition to this, West coasts are relatively wet and East coasts are relatively

dry. When planning a growing time-table it is crucial to understand ones local climate changes and seasonal weather

history (64). Local mountains and valleys divert air flow, causing moisture to collect and fall on specific areas,

while other areas are neglected. Knowledge of the location of a growing site effects plant productivity. Micro-movements

of wind and water patterns are understood through the physical movement of wind and water at increased or decreased

speeds. When wind and water travel through a landscape at a low velocity they flow around obstruction, but when

traveling at a high velocity they create eddies which are "cast" into stream flows, creating turbulent

patterns. Such patterns can be harmful to plants if not forecasted (66).

Other elements leading to the sustain success of food production are sun-sectors, the moon, and the important Edge

Effect.

Sun-sectors are the area in which optimal light exposure is received on present and future time periods. Measurements

of the movement of the sun provides a location that will best endure the elapse of time. Working with the moon

is also a crucial factor when planning planting and harvesting. By timing harvest with a full moon you will get

a higher and fuller yield. The reasoning behind this lies with the correlation of the level of water content in

relation to the cycle of the moon (67). This theory is part of permaculture's emphasis on taping into earthly and

celestial energy. The Edge Effect, also known as Eco-tone, is based on the area of overlap between two different

ecosystems. It is the most productive and highest in nutrients. A strategy for sustained maximization is to plant

in a spiral format or create spiral ponds in which to grow around (69). The spiral shape has the most edge effect,

hence one can increase productivity by just going with a natural pattern flow instead of manipulating soil or using

pesticides. The Edge Effect also carries on-to understanding niches of plant and animal species. Permaculture recognizes

that all plant an animals have specific niches of time, space and behavior. Within these niches exists a delicate

interaction and balance between animal and plant. We must work within the specific Niches.

Permaculture supports the idea of "the Spiral of Intervention". This concept addresses the theme that

nature should run its course and that minimal human intervention is best course of action. Bell offers the example

of losing sheep to hungry foxes. The ideal course of action is to do nothing and lose five sheep a year. If yield

is impaired beyond acceptable limits, begin on a step by step approach of intervention, each level an increasing

effect on the environment (71). The first step is to increase sheep herd to compensate for lost sheep (increased

output). The second step is to introduce a guard dog (biological intervention). The second step is to introduce

wire traps on the fox runs (mechanical intervention). The last step is to poison the fox holes (chemical intervention).

By following this method, and not advancing from one step to next unless completely necessary, a great deal of

unneeded damage and alteration of the natural world takes place (72). This methodology continues on to also gardening

and orchard practices. Bell supports not digging the land if plants can be grown without it. Trees should not be

pruned if yield is sustained without it. Human intervention drains and alters energy flows of ecosystems. Do nothing

if possible, minimal intervention if necessary (76).

This philosophy extends to the idea of "minimum effort, more effect". Western-industrial society is caught

with the mind-set that the more physical work and control over environment that the worker undertakes, the more

efficient and productive that work will be. Permaculture contests that idea. The mono-culture practice of industrial

farm work and energy is disproportionate to the amount of yield harvested. Stacking provides a practice of producing

similar level of yield but using less land. Stacking incorporates seldom used vertical space. Stacking is the inter-planting

of trees and low level plant life. Individual species yield is lowered, but combined yield is increased, providing

a healthy alternative to the dangers of mono-culture. Stacking allows for important plant diversity, provides resistance

to disease, healthy soil and wildlife habitat (77). Most of all this method of planting allows more local inputs

to be achieved, saved energy and increased local community self-reliance.

Slope management and erosion resistance are underlying factors important to all food production. It is important

to recognize that slopes more that 30 degrees should not be cultivated. Such slopes should be left permanent pasture

or woodlands. When ploughing a slope, erosion can be minimized by driving a tractor at right angles to the slope,

either on or off the contour. Erosion can also be halted by introducing pioneer plants on to the slope. Such plants

will grow quickly, retain nutrients and settle soil. Geotextiles are also used to prevent soil erosion. Woven materials

are applied to a hill and plants are gown within it in an interlocked fashion. The mesh system provides retentive

root structures (118).

The previously described practices are a small cross section of the many methods of permaculture. The common themes

within these practices that exist within all of the permaculture "way", are the incorporation and understanding

of natural patterns and movement toward planning and growing, and the minimalist approach of human intervention

on an ecosystem. These themes taken within a variety of contexts of world view and food production, will inevitably

lead to a more sustainable and efficient manner of existence.

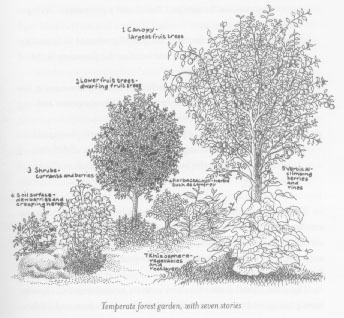

Forest gardening and the art of imitation

Forest gardening, as defined by Robert Hart, is a permaculture design that attempts to achieve

an economy of space, labor, and resources by imitating the natural processes of the forest (xiv). The forests of

the world have obviously survived for millennia without the guidance of human-made pesticides and irrigation. Nonetheless,

modern monoculture farming methods seem to deny the existence of natural yield, fighting against processes in order

to produce "high yield" crops. The result of this fight against nature are such absurdities as crops

that have a limited amount of vitamins and minerals due to depletions within the soil, for instance most corporate-made

bread must be fortified chemically because of the poor quality of monoculture wheat.

Permaculturists, looking at methods of alternative and "traditional" farmers, have "discovered"

the forest garden as an important asset to the world of agriculture. Robert Hart, in his book Forest Gardening:

Cultivating an Edible Landscape, writes, "The forest garden is far more than a system for supplying mankind's

material needs. It is a way of life and it also supplies people's spiritual needs by its beauty and the wealth

of wildlife that it creates" (xvi). Hart practices forest gardening, or agroforestry, on his farm in Shorpshire,

England. Here, he explores the many benefits and methods of this type of permaculture.

Like Mollison's diagram in the beginning of this paper, Hart does not attempt to revert back to a time prior to

the industrial age, rather he attempts to create a method of farming for the future that employs refined elements

of technology, such as solar power. To live with the forest is to reap the rewards of the forest — the medical,

economical, and personal. In the modern Cartesian paradigm this seems shortsighted and uneconomical; however, the

forest and forest gardening can provide a high yield sustainable system of agriculture that is equivalent or greater

than the current large-scale monoculture that has ravaged the environment. Benjamin Watson, in the "Foreword"

to Hart's book, gives the example of a family in the United Kingdom farming a 400 square foot area that only required

four hours a week of labor. Remarkably, their farm  yielded

the equivalent of fifteen tons per acre (Hart x).

yielded

the equivalent of fifteen tons per acre (Hart x).

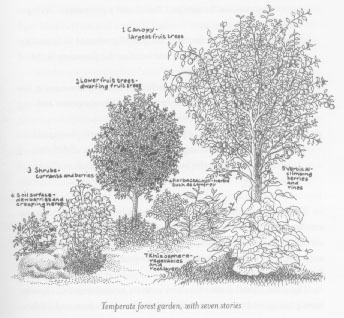

Forest Gardening is based on a seven tiered system that mimics the natural tiers of the forest, creating a self-sustaining

environment. The diagram to the left represents this system. The tallest layer of growth is the canopy, which contains

standard or dwarfed fruit trees. These trees help to "self-water" the entire garden because their deep

roots reach far into the earth and tap the spring veins, pumping the water from these depths up towards the roots

of the smaller plants. With these deep roots similarly come the capacity to naturally fertilize this agricultural

system due to the roots' ability to pull minerals from the subsoil to its neighboring plants. These trees should

also be compatible in order for them to successfully pollinate, thus, further eliminating human intervention in

the garden. The second layer is the "low tree layer" consisting of fruit and nut trees on dwarf root

stocks, which allows for an economy of space and light. The third layer is the shrub layer for fruit producing

bushes, which again maximizes the use of space and the availability of light, at the same time producing valuable

and enjoyable produce. Providing several valuable elements to the garden is the fourth tier, the herbaceous level.

Here, various edible herbs and vegetables aid in the prevention of pests and disease. Harmful Insects and other

intruders are repelled by the aroma of this herbaceous level. The fifth layer, again for the economy of space and

in imitation of the natural world, is the vertical layer, consisting of vines and other climbing plants. These

plants trained over trellis fences also help to create a barrier guarding against any large animals that might

want to enter the garden. By helping to prevent encroachment of weeds, the sixth layer of groundcover, such as

mint, helps to create an efficient mulch for the forest garden. Finally, the layer closest to the ground is the

"rhizosphere," consisting of shade tolerant plants (Hart 51-2). Most importantly, besides the economy

of space, these tiers provide two valuable elements that are found in the natural world, but absent from the modern

agricultural systems. Because the forest garden contains mostly perennial plants, the garden is "self-perpetuating."

Thus it supports "the no till agriculture," which is central to the practice of permaculture. Mollison,

in obvious support of Hart's theories, writes, "(Permaculture) is the working with, rather than against nature;

of protracted and thoughtful observation rather than protracted and thoughtless labour; and of looking at plants

and animals in all their functions, rather than treating elements as a single-product system" (Introduction

to Permaculture 1).

Imitating the natural processes and working with nature, forest gardening is a promising alternative to industrial

farming. Clearly, the modern consumer and agriculturist needs to re-evaluate their role in the destruction of the

environment. If people began to question their current practices, the success of alternatives, such as forest gardening,

could truly be judged. The testing of alternative methods of farming should be a priority to every consumer because

of the possbility of high quality produce that does not harm the environment.

Conclusion

We have reached a point in human development in which we must analyze our current structures of value and production

methods. It is imperative that we consider a new practical framework for food production and relationship with

nature. At the current rate we will exhaust all resources and space, causing irrevocable damage to our ecosystems

and societies. We must infuse a sense of environmental responsibilty and soical morality within science and technology.

Contemporary science and technology engage nature in an agressive and exploitative manner. The direct results of

this world view will be inhospitable living conditions and food barren of nutrients. This hazardous path can be

altered by recognizing the impermanance of our world view and agricultural practices. We are at a point in which

it is still possible to exit our current mode of existence and enter a new direction of sensibility and sustainablity.

Permaculture offers a gateway to such a direction. The switching of paradigms is a huge step, one that will require

both macro and micro adjustments of lifestyle. We believe that by understanding the basic principles of permaculture

embodied in the work of Masanobu Fukuoka, Graham Bell, Bill Mollison and Robert Hart, this movement can become

feasible in the minds of policy makers and individual citizens. Permaculture can begin tomorrow, but it takes time

for the full the reversal to complete. In time permaculture will help to be able to restructure capitalist industrialism,

and the world market system, by providing for a viable methodology and world view of sustainability.

Go works cited and suggested reading list

A brief look at Masanobu Fukuoka

A brief look at Bill Mollison

A brief look at Robert Hart

Return to home page

ng

clover to combat weeds, maintaining a healthy balance of predators and prey, etc (33-52). To do these things a

farmer must be in touch with the distinct natural system in his area. However, Fukuoka lays out what he calls the

"four principles of natural farming" as guidelines for any one who wants to try to create a natural garden.

These are :

ng

clover to combat weeds, maintaining a healthy balance of predators and prey, etc (33-52). To do these things a

farmer must be in touch with the distinct natural system in his area. However, Fukuoka lays out what he calls the

"four principles of natural farming" as guidelines for any one who wants to try to create a natural garden.

These are :

yielded

the equivalent of fifteen tons per acre (Hart x).

yielded

the equivalent of fifteen tons per acre (Hart x).