The Liberal Quandary Over Iraq

By GEORGE PACKERDecember 8, 2002

|

So let me rephrase the question. Why there is no organized liberal opposition to the war?

The answer to this question involves an interesting history, and it sheds light on the difficulties now confronting American liberals. The history goes back 10 years, when a war broke out in the middle of Europe. This war changed the way many American liberals, particularly liberal intellectuals, saw their country. Bosnia turned these liberals into hawks. People who from Vietnam on had never met an American military involvement they liked were now calling for U.S. air strikes to defend a multiethnic democracy against Serbian ethnic aggression. Suddenly the model was no longer Vietnam, it was World War II -- armed American power was all that stood in the way of genocide. Without the cold war to distort the debate, and with the inspiring example of the East bloc revolutions of 1989 still fresh, a number of liberal intellectuals in this country had a new idea. These writers and academics wanted to use American military power to serve goals like human rights and democracy -- especially when it was clear that nobody else would do it.

Many of them had cut their teeth in the antiwar movement of the 1960's, but by the early 90's, when some of them made trips to besieged Sarajevo, they had resolved their own private Vietnam syndromes. Together -- hardly vast in their numbers, but influential -- they advocated a new role for America in the world, which came down to American power on behalf of American ideals.

Against the liberal hawks there were two opposing tendencies. One was conservative: it loathed the idea of the American military being used for humanitarian missions and nation building and other forms of ''social work.'' This was the view of George W. Bush when he took office, and of all his key advisers. The other opposing tendency was leftist: it continued to view any U.S. military action as imperialist. This thinking prompted Noam Chomsky to leap to the defense of Slobodan Milosevic, and it dominates the narrow ideology of the new Iraq antiwar movement. Throughout the 90's, between the reflexively antiwar left and the coldblooded right, liberal hawks articulated the case for American engagement -- if need be, military engagement -- in the chaotic world of the post-cold war. And for 10 years of wars -- first in Bosnia, then Haiti, East Timor, Kosovo and, last year, in Afghanistan, which was a war of national security but had human rights as a side benefit -- what might be called the Bosnia consensus held.

But on the eve of what looks like the next American war, the Bosnia consensus has fallen apart. The argument that has broken out among these liberal hawks over Iraq is as fierce in its way as anything since Vietnam. This time the argument is taking place not just between people but within them, where the dilemmas and conflicts are all the more tormenting. What makes the agony over Iraq particularly intense is the new role of conservatives. Members of the Bush administration who had nothing but contempt for human rights talk until the day before yesterday have grabbed the banner of democracy and are waving it on behalf of the long-suffering Iraqi people. For liberal hawks, this is painful to watch.

In this strange interlude, with everyone waiting for war, I've had extended conversations with a number of these Bosnian-generation liberal intellectuals -- the ones who have done the most thinking and writing about how American power can be turned to good ends as well as bad, who don't see human rights and democracy as idealistic delusions, and who are struggling to figure out Iraq. I'm in their position; maybe you are, too. This Bosnian generation of liberal hawks is a minority within a minority, but they hold an important place in American public life, having worked out a new idea about America's role in the post-cold war world long before Sept. 11 woke the rest of the country up. An antiwar movement that seeks a broad appeal and an intelligent critique needs them. Oddly enough, President Bush needs them, too. The one level on which he hasn't even tried to make a case is the level of ideas. These liberal hawks could give a voice to his war aims, which he has largely kept to himself. They could make the case for war to suspicious Europeans and to wavering fellow Americans. They might even be able to explain the connection between Iraq and the war on terrorism. But first they would need to resolve their arguments with one another and themselves.

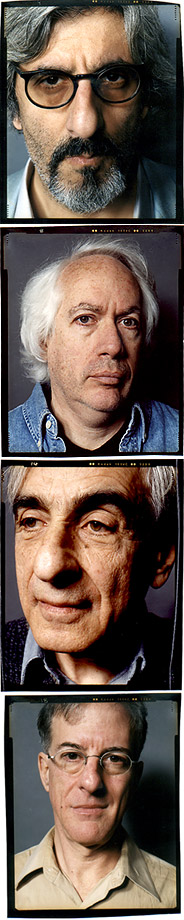

In my conversations, people who generally have little trouble making

up their minds and debating forcefully talked themselves through every side

of the question. ''This one's really difficult,'' said Michael Ignatieff,

the Canadian-born writer and thinker who has written a biography of the liberal

philosopher Isaiah Berlin along with numerous books and articles on human

rights. No one in recent years has supported humanitarian intervention more

vocally than Ignatieff, but he says he believes that Iraq represents something

different. ''I am having real trouble with this because it's not clear to

me that containment has failed,'' Ignatieff told me. This kind of self-interrogation

ends up with numerous arguments on either side of the ledger. Here's how

I break down the liberal internal debate.

For War

1. Saddam is cruel and dangerous.

2. Saddam has used weapons of mass destruction and has never stopped trying

to develop them.

3. Iraqis are suffering under tyranny and sanctions.

4. Democracy would benefit Iraqis.

5. A democratic Iraq could drain influence from repressive Saudi Arabia.

6. A democratic Iraq could unlock the Israeli-Palestinian stalemate.

7. A democratic Iraq could begin to liberalize the Arab world.

8. Al Qaeda will be at war with us regardless of what we do in Iraq.

Against War

1. Containment has worked for 10 years, and inspections could still work.

2. We shouldn't start wars without immediate provocation and international support.

3. We could inflict terrible casualties, and so could Saddam.

4. A regional war could break out, and anti-Americanism could build to a more dangerous level.

5. Democracy can't be imposed on a country like Iraq.

6. Bush's political aims are unknown, and his record is not reassuring.

7. America's will and capacity for nation building are too limited.

8. War in Iraq will distract from the war on terrorism and swell Al Qaeda's ranks.

At the heart of the matter is a battle between wish and fear. Fear generally proves stronger than wish, but it leaves a taste of disappointment on the tongue. Caution over Iraq puts liberal hawks, who are nothing if not moralists, in the psychologically unsettling position of defending a status quo they despise -- of sounding like the compromisers they used to denounce when it came to Bosnia. Fear means missing the chance for what Ignatieff calls ''a huge prize at the end.''

But wish makes a liberal hawk sound like a Bush hawk, blithely unconcerned about the dangers of American power. The liberal hawk is a liberal -- someone temperamentally prone to see the world as a complicated place.

This dilemma is every liberal's current dilemma.

The Theorist

After last year's terror attacks, Michael Walzer, the author of ''Just and Unjust Wars,'' among other books, published an article in the magazine he co-edits, Dissent, called ''Can There Be a Decent Left?'' Walzer harshly criticized leftists whose first instinct was to blame American policy for Sept. 11 and who refused to see the need for a war of self-defense against Al Qaeda. The article threw down an angry marker between the pro- and anti-interventionist left, and it drew heated attention to a 67-year-old political philosopher with a far-from-confrontational manner.

A year later, Walzer finds himself an ambivalent opponent of war in Iraq. Al Qaeda simplified things in favor of armed action; Iraq presents nothing but complication. ''The uncertainties right now are so great,'' he told me as we sat and talked at a cafe in Greenwich Village, ''and the prospects, the risks, so frightening, that the proportionality rule forces you the other way. And with a lot of other things going on -- suspicion of this government of ours, anger at the automatic anti-Americanism of people here and other places. It's all mixed up.''

Walzer is a strong advocate of multilateral action, and he faults the administration and its European allies for bringing out the worst in one another, American bellicosity and European complacency pushing the logic of events toward a war he says he doesn't believe is justified yet. The just-war theory requires that a threat be imminent before an attack is started. Since this is not yet the case with Iraq, an American war there wouldn't meet the criteria.

None of this means that Walzer is rallying opposition at teach-ins. In

the 1960's, he was willing to join an antiwar movement that he says he knew

would strengthen the hand of Vietnamese Communists ''because I thought they'd

already won. I would not join an antiwar movement that strengthened the hand

of Saddam.'' And yet he can't imagine one that doesn't. The nature of the

enemy makes it almost impossible to be outspoken for peace, a dilemma that

has created what he calls ''a kind of silent majority, a silent antiwar movement.''

Walzer's position offers cold comfort, for it ends up with Saddam still in

power. ''It leaves me unhappy,'' he says.

The Romantic

These days, Christopher Hitchens sounds anything but unhappy. His militant support, first for the war with Al Qaeda and now for a war in Iraq, has led him to break quite publicly with former comrades. He has vacated the column he wrote in The Nation for the past 20 years and has said harsh things about the ''masochists'' of the anti-American left. Hitchens's apostasy has generated nearly as much attention on the left as the war itself, but over a three-hour lunch in Washington, his position struck me as more judicious than its print version.

Hitchens agrees with the ''decent skepticism'' of liberals who distrust the administration's motives, but he has decided that hawks like Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz aim to use a democratic Iraq to end the regional dominance of Saudi Arabia. If this is the hidden agenda, Hitchens wants to force it into the open. He compares Saddam's Iraq with Ceausescu's Romania in 1989: it's going to implode anyway, and America should have a hand in the process.

In 1991, Hitchens was too suspicious of American motives to support the first gulf war -- a hangover, he says, from his days as a revolutionary socialist -- but on a visit to northern Iraq at the end of the war, he rode in a jeep with Kurdish fighters he admired who had taped pictures of the first George Bush to their windshield. It was a minor revelation. ''I'm not ashamed of my critique of the gulf war,'' he says, ''but I'm annoyed by how limited it was.''

Since then, Hitchens has steadily warmed to American power exercised on behalf of democracy. When I suggested that since Sept. 11 he has gone back to the 18th-century, when the struggle between the secular liberal Enlightenment and religious dark-age tyranny created the modern world, Hitchens readily agreed. ''After the dust settles, the only revolution left standing is the American one,'' he said. ''Americanization is the most revolutionary force in the world. There's almost no country where adopting the Americans wouldn't be the most radical thing they could do. I've always been a Paine-ite.''

British pamphleteer for the American revolution -- Hitchens has updated

the role for Iraq. His relish for war with radical Islamists and tyrants

(''You want to be a martyr? I'm here to help'') sounds like the bulldog pugnacity

of a British naval officer's son, which he is. It also suggests a deep desire,

and a romantic one, to join a revolution -- even if it's admittedly a ''revolution

from above.'' ''I feel much more like I used to in the 60's,'' he says, ''working

with revolutionaries. That's what I'm doing; I'm helping a very desperate

underground. That reminds me of my better days quite poignantly.'' Hitchens

has plans to drink Champagne with comrades in Baghdad around Valentine's

Day.

The Skeptic

''Revolution from above'' was Trotsky's mocking phrase for Stalin's use of the Communist Party to collectivize the Soviet Union. It implies coercion toward a notion of the good. David Rieff, whose book ''Slaughterhouse'' condemned the failure of Western powers to intervene in Bosnia, compares revolution from above to Plato's idea of ruling Guardians. What they share, says Rieff, is a desire to pursue utopian ends by undemocratic means.

''I always thought there was more in common between Human Rights Watch and the Bush administration than either would be comfortable thinking, because they both are revolutionaries -- in my view, quite dangerous radicals. They believe that virtue can be imposed by force of law and force of arms. Christopher has the same view with his sense that a democratic alternative can be imposed by force of arms in the Middle East.''

Unlike Hitchens, an Englishman who ''liked the United States enough to

have concluded when I was about 16 that I'd been born in the wrong country,''

Rieff is an American who grew up with a European education, traveled the

world as a teenager and always looked askance at the notion of America as

either savior or Satan. As an empire, America is neither better nor worse

than other empires -- but to expect it to behave like Amnesty International

is foolish. The difference between Bosnia and Iraq, Rieff says, is the difference

between supporting democracy and imposing it. The former was a moral imperative

as well as a strategic one; the latter is hubris. With Iraq, this hubris

is leading to ''a hideous mistake.'' ''I accept everything that the Bush

administration says about the wickedness of Saddam Hussein,'' Rieff says,

''but I do think it's a revolution too far.''

The Secularist

During the Congressional debates on the war resolution, it was just about impossible to hear an argument in favor of the administration without the words ''Munich'' and ''Chamberlain.'' The words ''Tonkin'' and ''Johnson'' were far rarer, which tells you something about the relative acceptability of World War II and Vietnam -- appeasement and quagmire -- as historical precedents. I wanted to ban all analogies, because they always seemed to be ways of avoiding the hardest questions. But the analogies are hard-wired, and Leon Wieseltier, the literary editor of The New Republic, is right to say that Americans of the postwar generation ''have operated with two primal scenes. One was the Second World War; one was the Vietnam War. And you can almost divide the camps on the use of American force between those whose model for its application was the Second World War and those whose model for its application was the Vietnam War.''

For Wieseltier, whose parents survived the Holocaust, the primal scene is American power helping to end evil. Shortly before I met him at his Washington home, Wieseltier had seen a TV documentary with rare footage of the gassing of Kurds by Saddam's army -- a reminder of a primal scene if ever there was one. But that was in 1988, when America failed to intervene. Today, American and British pilots in the no-fly zone are preventing the very genocide that Wieseltier feels would justify an invasion.

Wieseltier is a secular liberal in the classical sense. He says he believes that the separation of religion and power marked a violent rupture with the past. This rupture created a new and universal idea of freedom and equality -- one that Islamic societies around the world have not yet been ready to face. Sept. 11 was a cataclysmic ''refreshment'' of this idea, after years in which only money mattered. But terrorism should not turn liberals into simple-minded missionaries; being a secular liberal means accepting that the world is a difficult place. ''Democracy in Iraq would be a blessing, but it cannot be the main objective for embarking on a major war,'' Wieseltier says. ''If there is one thing that liberalism has no time for, it's an eschatological mentality. There is no single, sudden end to injustice. There's slow, steady, fitful progress toward a more decent and democratic world.''

Wieseltier says he believes that Saddam's weapons and fondness for using

them will probably necessitate a war, but unlike some other editors at The

New Republic, he is not eager to start one. ''We will certainly win,'' Wieseltier

says, ''but it is a war in which we are truly playing with fire.''

The Idealist

Paul Berman's book ''A Tale of Two Utopias: The Political Journey of the Generation of 1968'' traced a line from the rebellions of the 1960's to the nonviolent revolutions of 1989. It is essentially a line from leftism to liberalism. With the fall of the Berlin Wall, the great ideological battles of the 20th century seemed to have ended: liberal democracy reigned supreme.

Then came Sept. 11, which, Berman argues in a coming book called ''Terror and Liberalism,'' showed that, as it turns out, the 20th century isn't quite over yet.

''The terrorism we face right now is actually a form of totalitarianism,'' Berman told me in his Brooklyn apartment. ''The only possible way to oppose totalitarianism is with an alternative system, which is that of a liberal society.'' So the war that began on Sept. 11 is primarily a war of ideas, and Berman harshly criticizes Bush for failing to pursue it. ''We're going into a very complex and long war disarmed, in which our most important assets have been stripped away from us, which are our ideals and our ideas. He's sending us into war with one arm tied behind our back.''

Berman argues for a war in Iraq on three grounds: to free up the Middle East militarily for further actions against Al Qaeda, to liberate the Iraqi people from their dungeon and to establish ''a beachhead of Arab democracy'' and shift the region's center of gravity away from autocracy and theocracy and toward liberalization. In other words, war in Iraq has everything to do with the war on terrorism, and the dangers of an American military occupation that might not be seen by everyone in the region as ''pro-Muslim,'' though they worry Berman, don't deter him.

Perhaps the boldest intellectual move he makes is to claim a liberal descent for these ideas -- connecting the fall of the Berlin Wall, Bosnia, Kosovo, Sept. 11 and Iraq. This lineage, Berman claims, is represented not by George W. Bush but by Tony Blair, ''leader of the free world.'' Bush has presented the wars on terrorism and Saddam as matters of U.S. security. In fact, Berman says, they are wars for liberal civilization, and the rest of the democratic world should want to join. It doesn't bother Berman to hear conservative hawks at the Pentagon like Paul Wolfowitz talking similarly. ''If their language is sincere,'' he says, ''and there is an idealism among the neo-cons that echoes and reflects in some way the language of the liberal interventionists of the 90's, well, that would be a good thing.''

But Berman, unlike Hitchens, doubts their sincerity. And in the end, Berman can't support the administration's war plan, ''because I don't actually know -- I believe that no one actually knows -- what is the actual White House policy.'' So he is left in the familiar position of intellectuals, with an arsenal of ideas and no way to deploy them.

one chilly evening in late November, a panel discussion on Iraq was convened at New York University. The participants were liberal intellectuals, and one by one they framed reasonable arguments against a war in Iraq: inspections need time to work; the Bush doctrine has a dangerous agenda; the history of U.S. involvement in the Middle East is not encouraging. The audience of 150 New Yorkers seemed persuaded.

Then the last panelist spoke. He was an Iraqi dissident named Kanan Makiya, and he said, ''I'm afraid I'm going to strike a discordant note.'' He pointed out that Iraqis, who will pay the highest price in the event of an invasion, ''overwhelmingly want this war.'' He outlined a vision of postwar Iraq as a secular democracy with equal rights for all of its citizens. This vision would be new to the Arab world. ''It can be encouraged, or it can be crushed just like that. But think about what you're doing if you crush it.'' Makiya's voice rose as he came to an end. ''I rest my moral case on the following: if there's a sliver of a chance of it happening, a 5 to 10 percent chance, you have a moral obligation, I say, to do it.''

The effect was electrifying. The room, which just minutes earlier had settled into a sober and comfortable rejection of war, exploded in applause. The other panelists looked startled, and their reasonable arguments suddenly lay deflated on the table before them.

Michael Walzer, who was on the panel, smiled wanly. ''It's very hard to respond,'' he said.

It was hard, I thought, because Makiya had spoken the language beloved by

liberal hawks. He had met their hope of avoiding a war with an even greater

hope. He had given the people in the room an image of their own ideals.