Introduction

Introduction

Methodology

Methodology

Cynthia Barker

Cynthia Barker

Ruhamah Hayes

Ruhamah Hayes

Hannah Longbon

Hannah Longbon

Mary Steinhauer

Mary Steinhauer

Mary Chase

Mary Chase

Sophia Chase

Sophia Chase

Amelia Bloomer

Amelia Bloomer

Related Links

Related Links

Credits

Credits

Home

Home

Hannah Longbon

Consider the following assessment of the life of a typical farmerís wife in late-nineteenth-century Ohio: "She bore large families, labored over cooking stoves, bent over preserving kettles, churned butter, packed cold meats, served harvest dinners, and washed, swept, and dusted. She did two days work in one and had to like it...She had few pleasures, and they were simple and inexpensive." But as the author of the previous quote knew, the rural life of a farmerís wife was not all work. There were diversions: magazines and catalogs in the mail, church socials in town, and the annual meeting of a county agricultural society. County associations held "Farmersí Institutes" where they discussed Ohio agricultural conditions and farm life. A portion of almost every societyís agenda was given over to the consideration of the role of women on the farm. In 1891, Mrs. Hannah Longbon of Columbia Center, Ohio, offered her thoughts on "What a Farmerís Wife Should Know."

There is more demanded of the farmerís wife than of any other woman that must earn her own living. She must have brain, heart and muscle.

The successful farmerís wife should be independent and trustful of her own ability. Self-reliance comes from a cultivated intellect, a well disciplined heart and a sound constitution. With these she is the happiest woman on earth.

Womanís real worth is in her home, and nowhere is practical wisdom better illustrated. Consequently she must first have a thorough knowledge of herself. She must know her power of endurance, her capabilities, her tastes and all her other endowments of nature, and those which she lacks she must cultivate and strengthen by practice.

After this the next most essential thing is an entire knowledge of domestic economy, for the physical and moral health of her household rests upon her to a great extent.

|

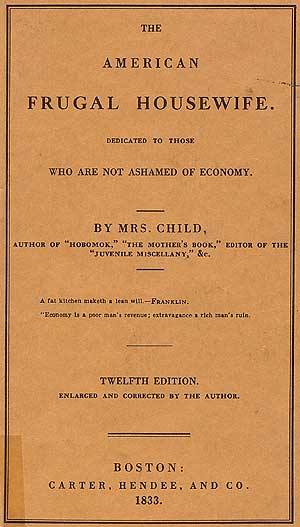

A popular domestic manual in the

|

The properties of food and the best method of preparing it is a knowledge every woman should have. No one has mastered the art of cooking who does not know something of the chemistry of food and the purpose they serve in the system. It seems to me that the noblest lesson for womanhood is to know of the waste and supply of the human body and that which builds up the muscle, nerve and brain of her family. Therefore, she must know the chemistry of food. She should know that a person working in the open air, as a farmer, can not exist and work on the diet of a brain worker, but that he needs food of a nitrogenous or muscle-making element--such as vegetable, grain and lean meat--and that he can not do a dayís work on the farm on novelties and delicacies, and that her children need a different diet than an adult. Good light-bread is the most essential food on the farm. Pharaoh once hung his chief baker, and if the cause thereof was poor bread, I do not wonder at it. The old adage is that "Bread is the staff of life," has sound sense in it, if it is food light-bread. But many a farmerís wife deals out stones instead of bread to her family.

She must know how to cook and bake as most conducive to the health of her family, for the first and greatest blessing God bestowed upon us is life; but life without health is almost a burden and a curse. She should understand the laws of hygiene, of the home and farm where they live.

She should be health inspector, if her husband is too busily engaged, or is not capable. In cities and towns one is provided for by the law, which prevents a great amount of sickness. She should understand the chemical analysis of water so as to be able to ascertain if it is pure or if the barnyard or other refuses are leached into the contents of "the old oaken bucket," which often overflows with poisonous germs.

She should know how to keep the back dooryard respectable, and not a receptacle for everything not in use or which has not found its proper place, for dirt is only matter out of place. The cellar, too, must be cared for by her, or at least inspected by her.

Why should farmersí families in the country, away from the bad vapors of the city, be so subject to malignant diseases? There is far more sickness among farmers than there ought to be. Bad conditioned cellars, small, close sleeping rooms, having the dooryard filled with too much shrubbery as to obstruct sunlight and the free circulation of air, are some of the agents of disease that the farmerís wife has to battle with. Cleanliness is essential to health and is just as necessary in the country as in the city.

A farmerís wife should understand botany to some extent, also the medicinal qualities of herbs and plants within her reach, for with them she can shorten doctor bills--for many a person lies buried beneath the herb or weed that would have aided nature in restoring him to health and activity.

If she insists on regular eating, pure water, freedom of dress, with plenty of sunshine and pure air, which all farmers have the privilege of enjoying, she will secure for her family that health and happiness which by nature is or ought to be our inheritance.

Dress among the farmers is almost always a secondary matter, and there is too much neglect of personal appearance--and the largest part is among the women; she seems to think dress amounts to nothing, or that she has no time to waste on dress--but here she makes a serious mistake. I think that is one of the reasons that farmers have so many epithets applied to them, and that they must take a back seat on many occasions. In a farmer, possibly, genius might cause slovenly garments to be overlooked; but no genius can make a carelessly attired farmerís wife look respectable. I do not mean that because we can not buy the richest fabric, we must dress out of taste, for taste costs no money, only a little exercise of the brain. Not that she should be governed by fashion, by exposing one member of the body, and piling a heap of cloth on another member, but harmony of cloth and texture, in accordance with her means. She must be able to buy suitable dry goods for the family. Farmers need different clothing that city folks. She must be a general seamstress and dress-maker; do the tailoring for the small boy, and surely know how to patch or mend; ought to know how to trim a hat for a girl, or possibly for herself; know how to raise poultry and calves once in a while, to be sure; know how to harness a horse, and care for one if necessary. I donít know if she should be concerned about the milking or not; if she does, it should only be in case of an emergency, for the house must go at the expense of the milking. Should know that "cleanliness is next to Godliness: buttermaking, as well as in every think else; and at what temperature cream rises best, how long it should stand before churning, and at what temperature to churn, and it will save her a great amount of labor. She should use her brain more at butter-making, and she will use her muscle less. She ought to know what crops are planted and reaped, and the amount of labor required in the operation. Should know the income and expenditure of the farm, and what taxes are paid, that she may not ignorantly waste her husbandís product, which means his labor. Ruskin, the English critic, says, "To waste the labor of any man, is to kill him." The policy that she is his only heir, is getting threadbare, for woman has proves that she is just as capable of carrying on business as a man only, he wonít give her half a chance. She should understand political economy, and how to sell and buy farm products--in what shape they are most marketable; what products are in greatest demand, and where and hen they will bring the highest price. Not that she should rule the farm, but, that she should be capable and understand their affairs. Duties never clash, for "united they stand, divided they fall." She must practice the motto of "early to bed, and early to rise," which gives her satisfaction of knowing its divine service, by getting up and earning her breakfast before she eats it.

|

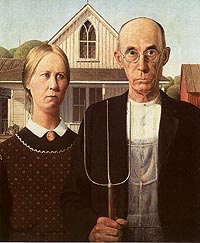

Grant Wood, American Gothic

|

If there are signs of a farmer losing his farm, some of the first questions that will be asked are, did they rise early? Was his wife economical, or could she waste more with the teaspoon than her husband could earn with the shovel? Were their affairs well regulated? Did she help him in any way? Or did he have to wait on her half the forenoon, and come in early to help her get supper in the evening?

A farmerís wife must be vigilant, for "eternal vigilance is the price of liberty" as much on the farm to-day, as it was in the days of Patrick Henry. You know that farmers as a class, are called penurious, stingy, etc., and that their wives are stingier than they are.

As a class the farmers come nearer to eating bread in the sweat of their face than any other people. He must work hard in this day of commission men and adulteration, which has a tendency to get him in a rut, and often he does not look beyond. They should guard against this. To provide for others and out own comfort and independence is honorable and greatly to be commended; but that a farmer and his wife should work and slave in all sorts of weather, all their lives, even toward declining years, allowing themselves no pleasure or comfort, shows that they are narrow-souled and miserly. Money is a power with a farmer after a sort; but intelligence, free heartedness and moral virtue are nobler powers.