|

|

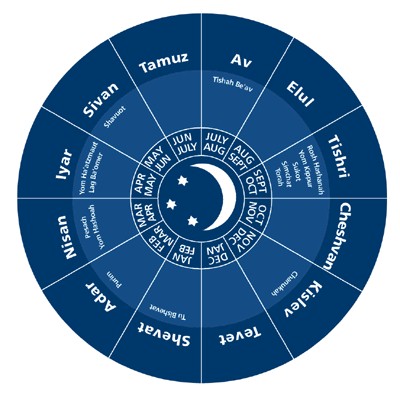

Background Before the 4th century, the Jewish calendar was not fixed, but rather, was based on the cycles of the moon, which happen every 29 to 30 days. The new month was determined by observation. When a new moon had been reported by enough reliable witnesses, the court would declare a new month and fires would be lit on the mountains that surrounded Jerusalem. These signal fires would been seen by neighboring cities, where more fires would be lit, until news of the new moon spread "like wildfire" from Israel to the Diaspora. Rosh Chodesh is the celebration of the new moon and a time of renewal, commemorated 11 times throughout the year. Witnessing the new moon was replaced in the time of Hillel II (358-9 CE) with astronomical calculations and the present Jewish calendar.(Rosh Hodesh Study Group in Columbia, MD) |

|

liturgical calendar image from Lycos Image Gallery and Pictures Now |

Rosh: head, beginning

Chodesh: month

Molad: birth, refers to the moment when the new moon appears

Lavannah/Yareyah: moon

(Bureau of Jewish Education)

|

|

|

In ancient times a shofar (ram's horn) would be blown every new moon. The shofar was also blown on Rosh Hashannah, at the end of Yom Kippur, and every morning of the month of Elul. image from Lycos Image Gallery and Pictures Now |

The observance of Rosh Chodesh was the one of the first commandments given to the entire Jewish community. While waiting for Moses to return from the mountain, the Israelites became impatient. They asked Aaron to make them a god to worship. Aaron built a Golden Calf out of wood and gold jewelry that they made sacrifices to and worshiped. God became very angry and almost destroyed them but Moses' pleading saved the Israelites. In the midrash Pirke DeRabbi Eliezer, chapter 45, sages tell that Hebrew women were rewarded for refusing to contribute their jewelry to the creation of the Golden Calf. God granted them a holy day of no work, Rosh Chodesh. It is the custom to wear new clothes on Rosh Chodesh.(Notre Dame University)

|

|

|

The Golden Calf image from Lycos Image Gallery and Pictures Now |

|

A thousand years after its revelation, observance of Rosh Chodesh was forbidden during the Syrian-Greek persecution along with the Sabbath and circumcision. The grouping of Rosh Chodesh with these essential commandments indicates its importance. Since Jewish festivals were entirely calendar based and the calendar required witnessing and proclaiming the new moon, without the calendar there would be no festivals. By stopping the celebration of Rosh Chodesh, The Syrian-Greeks could also eliminate many of the mitzvot. In addition, the Syrian-Greeks strove to eradicate the notion of Jewish renewal. The new moon symbolized the rising up of the Jewish people. Just as the moon disappears and returns every month, the Jews thought of themselves as suffering exile and persecution but renewing themselves continually until the coming of the Messiah. (Torah and Tradition) |

|

circle calendar |

Women especially have used Rosh Chodesh as a time for celebration. One reason is the association of women with the cycles of the moon. Rosh Chodesh is one of the common subjects of tkhines, petitionary prayers of Jewish women from Eastern Europe that emphasize women finding God in their unique domestic and mothering roles. Rosh Hodesh is announced on the preceding Shabbat with a special benediction within the Torah service. This includes a blessing of the upcoming month for peace and long, good life, and for the speedy coming of Moshiach, the messiah. It is celebrated with a partial Hallel, and with a musaf, which acts as a reminder of the sacrifice that was brought on Rosh Chodesh in ancient times. (Bureau of Jewish Education)

In the early 1970s women began to gather to reflect on women's spirituality and Jewish women in ritual. The small size of the groups created an atmosphere of support and a forum for study. The women began to develop several themes for the Rosh Chodesh ceremonies, the most popular being rebirth, renewal, fertility, nature and cycles of life. Common ritual practices, foods and liturgies emerged, including tzedakah (charity, giving money), candles, feasts, and water images, seedy fruits, round challot, crescent rolls, eggs, and sprouts, and Hallel psalms and Birkhat HaMazon (thanksgiving following meals). (Rosh Chodesh Study Group in Columbia, MD)

Judith Plaskow, in her book Standing Again at Sinai, argues that modern women look to women of their ancestry as models of spiritual expression. The rituals through which Jewish women do this include Rosh Chodesh, casting circles, goddess invocation, and ancient prayer prostration. However, Plaskow carefully notes that the simple fact that women of the past practiced these rituals does not make them superior to the traditional rituals and practices of men. Normatively, recovering past Jewish women's experiences reveals Judaism to be complex and shows the broadness and variation that lies within the Torah. Knowledge of the spiritual lives of past women can liberate modern women to explore innovative ways of participating in Judaism. Because the Torah is considered to be in constant construction, women's Torah has not yet fully been revealed. Therefore, creating a solidarity with Jewish women of the past can help modern women find themselves and their Torah within the patriarchy of Judaism. (Plaskow 51)

Plaskow advocates speaking and acting out the recovery of the Judaism of the past. Because Rosh Chodesh is one of the earliest Jewish feminine rituals, its modern celebration serves to acknowledge and restore the traditional observances of past women. Also, the ritual is simple enough to allow for modern interpretation and experimentation. Because the primary goal of Rosh Chodesh groups is to serve the spiritual needs of the groups, many groups generate themes from the particular month they are celebrating, or the concerns or experiences of the individuals of the group. (Plaskow 51) Click here for more information about Rosh Chodesh groups and how to create your own.

The following is a modern tkhine by a woman Rabbinical student, Geela Rayzel Raphel.

Sacred Mother of the Moon, You have given us this time of Rosh Hodesh for enjoyment and renewal. As your daughters gather in darkness, we attune to your Sacred energy. Your crescent sign, a reminder of the waxing cycles of Jewish people, is for us a symbol of Your ever present ability to restore our souls. We light candles to honor Your presence and welcome You with warmth as our female ancestors did in the desert.

Shechinah, Feminine Divine Presence, You have remained with us through hard times. Observing Rosh Hodesh was almost a forgotten observance, yet You again have demonstrated Your steadfastness by helping us recover our sacred time. Be with us again as we enter this new month filling our life with bounty and blessing.

This tkhine for group blessing seeks restoration of the soul and divine blessing. It emphasizes psychological transformation and indicates a connection to tradition even in the transformation of tradition. (Chava Weissler 169)

In the sixteenth century, women observed the eve of the new moon, Yom Kippur Katan, with men, in penitence. In the eighteenth century, influenced by mystical pietism, men observed the eve of the new moon separated from women as a day of fasting and atonement. Meanwhile, women developed their own tkhine on the Sabbath preceding the new moon in the liturgy that announced the new moon. (Chava Weissler, Voices of the Matriarchs: 23, 112)

For Ashkenazic Jews, Yom Kippur Katan is a day for reflection, repentance, examination of the ways

time is used, and gathering to celebrate creation and the renewal of life.

|

Moroccan Jewish Woman image from Lycos Image Gallery and Pictures Now |

In her book, Voices of the Matriarchs, Chava Weissler offers an Ashkenazic Yom Kippur Katan liturgy. Leah argues that women tend not to pray for the sake of the Shekhinah (the presence on God in the world), rather for their own material benefit. She writes the Tkhine of the Matriarchs, and claims her intention is to discourage women from reciting a Rosh Chodesh tkhine which includes a confession and requests for forgiveness of sins. Leah was troubled by the fact that confession had made its way into the liturgy of a festival day. So, she writes:

Leah's tkhine concerns luck, sustenance, and protection. Leah asks that God remember the merits of the matriarchs (Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and herself) and for their sake, to redeem Israel. It raises the interesting issues of the ways in which women gain merit. Leah seems to say that they do through their ancestors, ultimately, the matriarchs. (Weissler 112) |

Kiddush Hal'vanah, "Sanctification of the Moon"

| This ritual involves the observation of the new moon and mimics ancient witnessing of the new month. Individuals or groups stand outside on a clear night when the waxing moon is visible (usually between the 3rd and 14th day of the lunar month). In following Yemenite custom, some people light candles to remember the signal fires that were lit in Jerusalem to announce the new moon. Psalm 148 is usually read, or other biblical passages that discuss the moon. The traditional blessing follows: |

new moon image from Time Service Department, U.S. Naval Observatory |

"Bountiful are you, Adonai, our God, Sovereign of the universe, whose word created the heaven, whose breath created all they contain. God set laws for them, that they should never deviate from their assigned task. Happily, gladly, they do the will of their dependable creator, whose work is dependable. To the moon God said: 'Renew your crown of beauty for those with heavy bellies, who are also destined to be renewed like her, and to glorify their Creator for the sake of God's glorious sovereignty.' Bountiful are you, Adonai, who renews the months." (Bureau of Jewish Education)

Then the participants stand tall and reach up with their arms toward the moon saying, "Even as I raise myself up to you but cannot touch you, so may my foes be unable to touch me with evil intent." However, since with modern technology we now actually can touch the moon, another version of this passage says, "Just as in our generation we can touch the moon, so our enemies can touch us. So all of us must seek to make our enemies into our friends, so that no enemy will seek to touch us in a deadly way, so that all human beings will feel their hearts touched by each other's pain." (adapted by Arthur Waskow, Bureau of Jewish Education)

The ceremony closes with participants wishing each other "Shalom aleichem. Aleichem shalom," "Peace be with you. May you have peace," a song and a reading from the Song of Songs or Psalm 121, which discusses God's nightly protection. (Bureau of Jewish Education)

|

|

|

zodiac calendar, image from Rosh Hodesh Study Group in Columbia, MD |

Conclusion

Rosh Hodesh is a celebration of renewal and sustenance. The new moon is powerful in its ancient determination of the ritual calendar and therefore the mitzvot. God's granting of this essential holiday to women, as a time of rest, shows God's recognition of women's commitment and important role in the renewal and sustenance of the Israelite people. It was the women who were patient and trusting of God and refused to worship idols. The long history of the celebration coupled with its lack of a set ritual allows women creativity and power to determine their own specific way of worshipping while remaining connected to the women of their ancestry. Rosh Chodesh brings Jewish women of past and present all times together and helps them create one large community where they can explore their faith and role in the Jewish tradition.

Bibliography

Plaskow, Judith. Standing Again at Sinai. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1990.

Weissler, Chava. Voices of the Matriarchs: Listening to the Prayers of Early Modern Jewish Women. Boston: Beacon Press, 1998.

Rosh Hodesh Study Group in Columbia, MD explanation of Rosh Chodesh

Notre Dame University: story of the Golden Calf

Bureau of Jewish Education: search for Rosh Hodesh, then find info on starting your own group