February 04, 2001

The 1989 massacre still haunts the regime, having ruined the lives of its many victims and their families.

Photograph by Jacques Langevin/Corbis Sygma | |

Related Articles • New Window on Tiananmen Square Crackdown (Jan. 6, 2001) • International Home

Issue in Depth

Text

Slide Show

Related Site

|

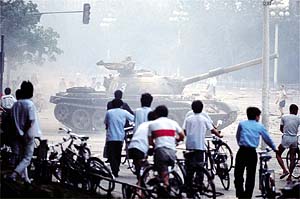

hroughout the spring of 1989, Tiananmen Square, the political heart of Beijing, was engulfed in protests. By June, many of the people filling the square and surrounding streets were spectators with only the vaguest political motives. It was into these crowds that the People's Liberation Army opened fire in the early hours of June 4, killing hundreds or even thousands of civilians. No one outside the inner councils of the Chinese government knows for certain how many people died or why.

hroughout the spring of 1989, Tiananmen Square, the political heart of Beijing, was engulfed in protests. By June, many of the people filling the square and surrounding streets were spectators with only the vaguest political motives. It was into these crowds that the People's Liberation Army opened fire in the early hours of June 4, killing hundreds or even thousands of civilians. No one outside the inner councils of the Chinese government knows for certain how many people died or why.

The recently published "Tiananmen Papers," transcripts of government documents reportedly smuggled out of the country by a disaffected Chinese official, claim to tell what happened behind the high red walls of China's leadership compound in the weeks before the massacre. Their appearance suggests that, even within the government, the wounds of Tiananmen still fester, and that some insiders are ready to reassess the wisdom of the decisions that led to the shooting that night.

For no one is that reckoning more pressing than the surviving victims of the massacre, people whose lives were ruined by that brutal sweep of Beijing's streets. They're a disparate group: maimed student leaders, stricken bystanders, bereft parents and young widows left behind. June 4 shattered their faith in a government whose mistakes they had obediently endured since childhood. They insist that only a full reassessment of the events of that night can begin to repair the damage.

Though few of them count themselves as political dissidents, their association with June 4 has made them suspect in their own country. Many are watched by teams of police officers charged with tracking the movements and activities of people deemed potential threats to the Communist Party. Some are regularly followed or have their telephones tapped. Others are restricted from traveling freely within China, let alone abroad.

Despite the risks, some of them agreed to talk and be photographed in one of the country's most public places: the Forbidden City, a vermilion maze in which China's emperors once lived. Now open to the public, the palace sits at the head of Tiananmen Square, which, since the June 4 killings, has become far too sensitive a place for them to gather. These days, it is a site of stubborn protests by -- and, apparently, the recent self-immolation of -- members of the outlawed spiritual movement Falun Gong.

Not everyone is willing to be photographed. Among those who refused is a 36-year-old blind man who has never seen his daughter, now 11. On the night of June 3, he ventured out in search of his pregnant wife. A bullet passed across his face, puncturing the bridge of his nose and rupturing both eyeballs. Today he ekes out a living as a masseur in a clinic of blind masseurs. The most immediate images left from his life with sight are of the tanks and troops and dying civilians he saw that night and then one final flash of light.

Almost all of the victims, though, are eager for someone to listen to them. Here are the stories of four of them, two surviving victims and two relatives.

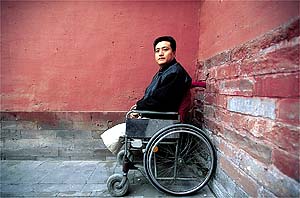

FANG ZHENG

'My girlfriend left me under pressure from her family.'

Photograph by

I was a Communist Party member, and I was leading about 40 students from my college out of Tiananmen Square early on the morning of June 4. The crackdown was pretty much over.

Several girls were with us, and one was really scared. I told her not to worry, that I'd stay with her. But when we turned onto Changan Avenue, the army began shooting tear gas at us. The girl I was with stumbled and was choking on the gas. We were in the roadway, and I helped her over the railing onto the sidewalk. As I was doing so, tanks rushed toward us. There was no time to get over the barrier and no room between it and the tanks.

I threw myself face down onto the road and my torso landed between the treads of one tank. My pants caught in the treads, and I was dragged under the tank. And then all of a sudden the pants tore off, and I thumped to the ground. My ears rang and my sight slowly went black. But I saw the whiteness of bone from a leg before I lost consciousness. I came to the next day in the hospital and asked if I had lost a foot because I remembered that when I had seen the bone I hadn't seen a foot below it. Both my legs had already been amputated, one above the knee and one below.

I used to be a sprinter, but after my injury I began training with the discus and the javelin, and in 1992 I won two gold medals in the national disabled games. Finally, a friend got me a job with a real-estate company in Hainan. So I moved there with my girlfriend.

Craig S. Smith is the Shanghai bureau chief of The Times.

In 1994, I was selected to participate in the Far East and South Pacific Disabled Games. But in late July, an official called me in to say that they knew how I had been injured and were concerned because there would be a lot of international journalists at the games. I promised that I wouldn't talk to anyone about how I lost my legs. A few days later, a man from the China Sports Ministry told me I should pack my things, I was going back to Hainan. Later that year, the real-estate market in Hainan collapsed, and the company I was working for closed. I built a small stand and began selling cigarettes and soda to get by. I couldn't find another job.

In early 1995, my girlfriend left me under pressure from her family. The police had warned that she could face trouble if she stayed with me. Her family also worried that my earning power wasn't strong enough to support her.

Later in 1995 the stand was knocked down because the site was being developed. I still don't have a job. The police often question me or the people I'm seen with, and employers are afraid to hire me.

Of course, I hope things will change. I've thought of trying legal channels to seek compensation from the government. But realistically, it isn't very likely that the government will reverse its position on June 4 anytime soon. Maybe they will start in some gradual way, like by saying that using tanks was a mistake.

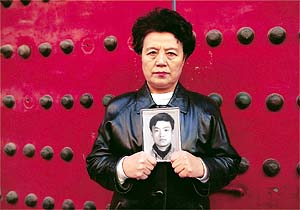

ZHANG XIANLING

'He was just 19, a junior in high school.'

Photograph by

After my son was shot, the army buried his body in a shallow grave on Changan Avenue. A torrential rain a few days later exposed some of the bodies in the grave, and they began to smell. So the school reported it to the Xicheng District public security bureau, and they dug the bodies up.

My son had recently completed his high-school military training and was wearing army pants the night he died. So the people who dug him up assumed he was a soldier and sent him to a hospital morgue. We were lucky, because I was told that the other bodies buried there were cremated without being identified. If he hadn't been wearing army pants, we still might not know what happened to him. He was just 19, a junior in high school.

The night he died, he asked me if I thought there would be shooting. I said, "No, even during the power struggle with the Gang of Four they didn't shoot." But I said they might hit people with sticks, so he should wear a motorcycle helmet that a neighbor had left in the laundry room.

I didn't want him to get involved, but he liked photography and said he wanted to capture this moment in history. He took my Olympus camera. He also took the helmet.

He wasn't in his room the next morning. We checked 24 hospitals, but there was no sign of him. I broke down and couldn't control my sobbing. We were finally notified on June 14 that his body had been found.

When my son's body was exhumed, his forehead was wrapped in a bandage. I wanted to meet the person who had taken care of him and finally found him. He was a doctor, a recent graduate.

Bystanders said my son was shot at about 1 a.m. They said he rushed out of the crowd and took a picture as the troops approached. A soldier apparently fired at the flash. He was hit in the forehead, and the bullet came out behind his left ear.

The doctor said my son died at 3 a.m. Two other people wounded there also died. The doctors stayed with the bodies until about 6 a.m., when the soldiers forced them to leave.

When we recovered the body, one shoe and one of the lenses of his glasses were missing. His camera was also gone. Someone must have taken it, and they might have saved the film. If so, it holds an image of the last thing my son saw, perhaps even a picture of his killer.

QI ZHIYONG

'I couldn't believe that the P.L.A. would shoot it's own people.'

Photograph by

I had a job painting a restaurant near Tiananmen Square. On the afternoon of June 3, I bicycled to work with two colleagues. We planned to work into the evening because it was so hot. When we got near the square, the crowd was so thick we had to leave our bikes on the north side of the street and continue on foot.

That evening, we went to the square. About 11 p.m., there was an announcement on the loudspeakers warning everyone to leave or face the consequences, so I headed toward the place where I had left my bike. I was going to cross Changan Avenue when tanks and armored cars came rushing toward us, and I ran with other people into a lane. We stood at the mouth of the lane listening to the gunfire. I said that I thought they were rubber bullets. But just as I said that, something hit my leg. I reached down and blood was spurting out like a fountain. Three of us standing at the mouth of the lane were hit. Two died on the spot.

That was about 1 a.m. By the time I arrived at a hospital operating room it was 3:30 a.m., but there were so many patients that I wasn't operated on until 5:40. The operation lasted six hours. But my left leg was too far gone, and on June 13 they took it off.

I wondered, Why was I suffering this way? I was born in the new society. I grew up under the red flag. From childhood I had always hoped to be a People's Liberation Army soldier and defend my country. I couldn't believe that the P.L.A. would shoot its own people.

At that moment, I woke up to what the Chinese Communist Party was all about. When people ask me now how old I am, I say I'm 11 years old.

Later, my work unit categorized me as a bao tu, or thug, and didn't offer much help. They give me 270 yuan, about $32, a month in disability payments, and I make ends meet by running a small stand that sells beer and cigarettes and candy.

YIN MIN

'His death shattered my faith in the government.'

Photograph by

I'm a doctor, and I was visiting the sick child of a neighbor on the evening of June 3. From the window of the neighbor's sixth-floor apartment, I could see my son in our apartment across the way. He was reading a schoolbook by the lamplight there. He had already begun studying for his college entrance exams, and I felt great comfort seeing him work so hard. I didn't know that was the last time I would see him alive.

He apparently put down the book around midnight. Neighbors say they saw him leave on his bicycle at about a quarter past the hour. He never returned. We searched for him at the hospitals all the next day. On June 5, my husband found him at one. The doctors told me that he had been shot three times at around 2 a.m. The fatal bullet hit him in the back of his head and lodged in his brain.

Four young men took turns carrying him on their backs to the hospital. The doctor said his heart was still beating when he arrived. The doctor said that because he was so young, such an attractive boy, they spent more time on him than on others. But he died. He was only 19 years and 4 months old.

My colleagues went to recover the body. They washed and dressed him and took him to Babao Shan cemetery. When I saw him there, his face was dark with blood. I opened his shirt to touch him and saw bruises there. They looked as if they had been made with a rifle butt. The doctors said he was shot at close range.

We had no way of knowing exactly where our son died. But several months later I dreamed about the place and went looking for it the next morning. I found what I had seen in my dream. It was a small park, in front of a dormitory, east of the Muxudi bus stop. The park doesn't exist anymore because they have widened the road. But I'm sure that this is the place where my son was killed.

After cremating my son's remains, I put his ashes in my bedroom. Now I talk to him about my depression and my sadness.

His death shattered my faith in the government in ways that the Cultural Revolution never did. That involved factions fighting each other, and the people who lost were blamed. But this was the government against the common people, and it has never admitted its fault. I want the government to acknowledge what happened and let the courts prosecute those people who were responsible.