|

February 10, 2005

|

| |

|

![]() ENGFENG,

China - Well-worn flagstones lead up a gentle gradient, through an imposing

gate, past huge statues of fierce guardian spirits. The tiled eaves

of a temple loom behind a giant ginkgo tree, all but groaning under

the weight of a heavy snow.

ENGFENG,

China - Well-worn flagstones lead up a gentle gradient, through an imposing

gate, past huge statues of fierce guardian spirits. The tiled eaves

of a temple loom behind a giant ginkgo tree, all but groaning under

the weight of a heavy snow.

Suddenly, the pounding of hammers and the whine of an electric saw interrupt the reverie. Only then does it dawn that this is no ancient temple but a re-creation. The impression is confirmed by a glance at the colors in the rafters, impossibly bright for anything truly old.

Discordant sensations may be forgiven. Like any temple, the birthplace of China's most famous form of kung fu is supposed to be a space of tranquillity and meditation. Yet Shaolin has become such a fixture of Chinese popular culture that much of the life of this holy shrine involves greeting paying tourists who arrive year-round by the thousands.

| |

|

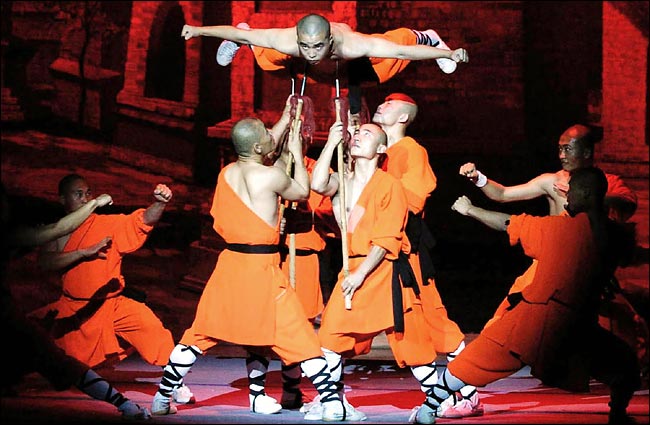

For the monks of Shaolin Temple, identity crises are nothing new. Is Shaolin kung fu popular entertainment or solemn exercise? Is it a money maker or tool of spiritual mastery? Is this idyllic site in the Song Mountains of Henan Province a contemplative retreat or a theme park? The short answer to all these questions is, of course, yes.

There are even two versions of how it all started. The official account, a blend of history and religious lore, places the origins of the Shaolin tradition in the sixth century. A Buddhist monk from India named Bodhidharma, or Damo, settled here then and began instructing local monks in scripture and the physical drills that are still said to be the basis of kung fu. But if the question is more about when this country went kung fu crazy, then the origins trace back several thousand films to "Shaolin Temple," featuring the Chinese action movie star Jet Li.

Mr. Li, a four-time national martial arts champion, filmed mainland China's first kung fu hit here in 1979 (it was released in the West in 1982), just as China was embarking on its economic liberalization. The moviemakers borrowed as their plot the then-dilapidated Shaolin Temple's most famous legend, the story of 13 monks who rescued the Tang emperor from a vicious warlord.

The rest is, as they say, history. The road to Shaolin Temple today is literally lined with kung fu academies, which at last count numbered over 50. The schools are huge, some with over 10,000 students who come from all over China to train throughout the year, including now in this season's bone-chilling weather, in hopes of becoming the country's next Jet Li.

| |

|

For the monks who run Shaolin, the explosive popularity of Shaolin kung fu has not been without problems. For one, anyone vaguely familiar with Chinese martial arts and with a little bit of business sense, here or abroad, can hang up a shingle claiming to run a Shaolin kung fu school.

The temple's leaders say they have had enough of this debasement, and have persuaded the Chinese government to declare the name a recognized brand, protecting it under the rules of the World Trade Organization. The temple is also on a short list for recognition as a United Nations World Heritage Site, protecting the name, which they see both as a valuable brand and a term of spiritual import.

"Shaolin wants to preserve our uniqueness, for the same reasons that developed countries value individuality," said the temple's leader, or abbot, who goes by the name Yongxin. "It's a process that the society has to go through, spreading standards. What Shaolin is trying to do is work from our origins, from the basics, and we're doing pretty well."

The monks' life, he said, was simple and austere, with frequent meditation and chanting prayer services. "It is a lifestyle that has lasted over 1,000 years," said Yongxin, a short, bald, pudgy man of 40 who pads about his chilly but ornate quarters in long, mustard-colored robes, attended to by tea-serving monks. "We get up at 4 a.m. and have breakfast at 7 a.m. and lunch by 11:30. There are morning and evening classes, prayers and scripture readings." There are also, he neglected to add, daily kung fu exercises.

Between Shaolin's distant Buddhist origins and its Hollywood-like revival, the temple has seen more than its share of ups and downs. It was nearly burned down in the 1920's, during China's civil war, and was damaged further under Japanese occupation 20 years later. Kung fu was banned under the Communists in the 1950's, and during the Cultural Revolution, in the 1960's, the monks, who were subjected to public humiliation and beatings, abandoned the temple altogether.

The current revival has been almost entirely overseen by Yongxin. Although he is reputed to be a kung fu master, like most of the monks here, his appearance is anything but fierce. Indeed, his most formidable weapon seems to be the mysterious government connections that have reputedly enabled him to reclaim the extensive lands surrounding the temple, clearing them of junky shops, hotels and other tourist traps.

"All across history, Shaolin Temple has served the emperors," said Liang Yiquan, 74, the director of the nearby Shaolin Epo Martial Arts School, commenting on the abbot's influence. "Now they serve the Communist Party. There's a political element to it."

Asked whether Shaolin's popularity was a blessing or a curse, Yongxin waxed philosophical. "Having so many schools teaching inauthentic kung fu may not be such a bad thing, as long as it can help promote Buddhism," he said. "We are not against pursuing commercial interests. We only hope we can play a positive role in the society, while not violating a spirit that is 1,500 years old."