April 15, 2002

COLUMN ONE

China's Mother Tongue Is Dying

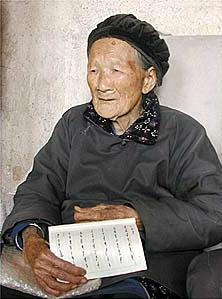

Generations of women passed down a unique form of writing that was kept away from men. Now a 95-year-old may be the last alive who grew up using nushu.

By HENRY CHU, Times Staff Writer

|

|

|

On its pages Yang has written the woeful story of a girl trapped in an unhappy marriage, a common lot among women in rural China. But the tale is not what attracts attention. It is how Yang recorded it: in a unique form of writing invented and passed down through generations by the women of Jiangyong—and kept apart from their fathers, husbands and sons.

Long before Western pop psychologists coined the concept of "he said, she said," the women here were putting it into living, daily practice. Using their special form of communication—called nushu, or women's script, in Chinese—they carved out their own private linguistic space in a world dominated by men. It was a rare act of female solidarity in one of the world's oldest civilizations, kept mostly hidden from public view until 20 years ago.

The language, mainly written but sometimes spoken or sung, enabled its users to share thoughts, spread gossip and swap experiences at a time when most of their sex in China were illiterate and often denied identities apart from their menfolk.

Confined to the home, the women of Jiangyong transformed objects of daily life into tools of greater intellectual independence. They copied down their writings in books, embroidered them into handkerchiefs and painted them onto paper fans. Their stories are recognizable to women everywhere. Wistful nushu poems lament over faraway friends, letters complain of nasty husbands and nastier mothers-in-law, jealous tales attack enemies and rivals.

The women circulated their texts among close companions, "sworn sisters" who formed small sororities that became crucial female support networks in the face of male domination. "Beside a well, one does not thirst," a popular nushu saying holds. "Beside a sister, one does not despair."

Scholars believe that Yang is the last woman alive who grew up with nushu as a vital part of her girlhood and adult life, the sole survivor of a tradition that will die when she does. Already, her hands are too unsteady to write much. The soul mates who once deciphered her script, giggled at her jokes, cried at her losses and then wrote back about their own lives are gone. And the younger generation, Yang's granddaughters and great-granddaughters, has no use for nushu. "Nobody's learning it now," Yang lamented. "They all go out to work."

A handful of Chinese and Western scholars is working to preserve the script, as are a few local women and government officials who hope to exploit its tourist value. But like Latin, nushu has ceased to function as a living language, driven to obsolescence by the universality of Mandarin Chinese and the availability of public education for girls, who see no need for a secret form of communication as their mothers once did. "It has no pertinence to anyone's lives anymore," said Cathy L. Silber, an authority on nushu who teaches at Williams College in Massachusetts.

Because the script was never codified, and because of slight variations from village to village, no precise count exists of the number of nushu characters invented over the years. Experts put the figure at between 600 and 1,000. Mandarin Chinese, by contrast, boasts at least 50,000 characters.

Unlike their Mandarin Chinese counterparts, nushu characters do not represent meanings but sounds. Visually, some nushu writing resembles Chinese, perhaps because wives and daughters watched their husbands and brothers learn the dominant language, memorized a few characters and then modified them for their own use.

But mostly, nushu and Chinese look as different as female and male, almost literally. Classic Chinese characters are bold and boxy, whereas nushu characters are wispy, often curvy and written at an elegant slant. Local residents liken nushu characters to the hieroglyphic-like scratchings on oracle bones, the earliest evidence of writing discovered in China.

Through generations, mothers passed on their knowledge of nushu to their daughters. Grandmothers taught granddaughters while they worked together at home, spinning, sewing, cooking and singing, segregated from the men. "We lived upstairs and didn't even go downstairs, much less go out to work," Yang recalled.

Occasionally, elite families hired tutors for their daughters. Female teachers could thus teach nushu in more formalized settings. Yang learned alongside a neighbor girl, Gao Yinxian, who eventually became a prolific nushu author. "I was about 10 years old or so," Yang said. "I was so happy first learning to sing the songs and then how to write."

Men Just Didn't Listen

The separation of the sexes meant that men took little notice of nushu, which stayed entirely in the female sphere. If men had listened closely, they might have been able to understand the language in its spoken form, which sounds similar to the local dialect of Jiangyong, an obscure county (pop. 240,000) in southern Hunan province.

But primarily, nushu is a written language. Composition followed certain conventions. Most writings are in verse, usually seven characters per line, similar to patterns found in Chinese oral literature, such as opera.

Many of the extant nushu texts, now in the hands of scholars, are sanchaoshu. These are special cloth booklets that were presented to a bride by the women in her family. Inside are songs and poems reflecting sadness at being separated and anger at the custom that forced a married woman to leave her childhood home for her husband's household. "The emperor has made the wrong rules," goes a popular refrain in many bridal books.

Letters served as a grapevine through which news and gossip could make the rounds. One letter tells the story of a distraught young newlywed whose husband in an arranged marriage turned out to be physically disabled. Another spreads word of a tiger attack in the fields.

A few juicy nushu texts drip with insult and sarcasm, angry missives that chew people out for bad behavior or some other offense, Silber said. One particularly acid-tongued woman wrote to another: "At least animals go into heat in season. But you, . . ." What prompted such venomous gusto is not clear from the letter, although it might be guessed.

More serious writings broached politics, at least in terms of their effects on domestic life. A song from the first half of the 20th century criticizes China's Nationalist government for conscripting too many sons into the army. Another describes how Japanese bombers forced residents to flee their villages and take refuge in the hillside caves around Jiangyong.

The only subject not covered in nushu writings appears to be finances, said professor Xie Zhimin, a nushu expert at the Central South China Institute for Nationalities in Hubei province. "My guess is that it's because women's status was still low and they weren't allowed to be in charge of money at home," Xie said.

Although the texts show a surprising degree of independent thought, Silber cautions against viewing them as subversive. True, the women complained about the emperor's rules on marriage, "which is a political statement," Silber said, "but it's not 'Let's overthrow the dynasty.' "

The origins of nushu are lost in legend. Some scholars theorize that the script was created more than 2,000 years ago, one of many tribal languages scattered across China before the first emperor, Qin Shihuangdi, unified the country in 221 BC and promulgated Chinese as the national tongue. The script then wound up in the hands of women as men switched to mastering the official language.

Another, more fanciful theory centers on a precocious girl from Jiangyong who was plucked from her childhood home to become an imperial concubine. "But she was so miserable in the palace that she developed nushu as a code to send letters of woe to the folks back home," Silber said.

Whatever its source, nushu is known to have existed at least by the start of the Taiping Rebellion in 1850. A coin from that period recently was found stamped with nushu characters.

For generations, the women of Jiangyong penned their letters, composed their poems and communicated among themselves with little outside intrusion. At worst, their writings mystified the men around them. One story has it that a woman picked up in another part of Hunan province during the 1950s or '60s was believed to be a spy after police found nushu texts in her possession, which they could not decipher.

Crackdown on Nushu

During the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, nushu was blasted as a feudalistic leftover. "The women who knew nushu, who used to get together to sing [nushu songs], were seized and protested against and criticized," said Zhou Shuoyi. "And the materials they had were confiscated and burned."

Zhou, 77, is a retired official of the Jiangyong county cultural bureau and is widely credited with exciting scholarly interest in nushu. He came across mention of the language as a child, and in the 1950s befriended women proficient in the script. In 1958, he was denounced as a "rightist," partly for his work on nushu, and sent to toil in the countryside as a farmer. Rehabilitated 20 years later, Zhou set about publicizing nushu to the outside world. By then, many of the women who knew the script had died; others were, at first, too afraid of being persecuted to resume writing.

Local officials see the language mostly as a tourist attraction. One village set up a nushu school, partly to draw tourists, but ran out of funds to keep it going. The teacher, Hu Meiyue, is the granddaughter of Gao Yinxian, the nushu writer. Hu, 40, has tried to pass on what she knows, but even her daughter shows little interest.

These days, many of the people whom Yang, the 95-year-old nushu speaker, meets with to discuss the secret script are foreign visitors and journalists. Her face is wizened, her hair nearly gone. But beneath crinkled folds, her eyes twinkle and her mouth curls up in a charming, toothless smile. She misses the days when she and her four "sworn sisters" shared stories, away from the prying eyes and ears of men.

"When I learned nushu, it was to meet with friends and sisters to exchange our thoughts and letters. We wrote what was in our hearts, our feelings," Yang said. "But now," she added with a sigh, "there's no use learning it anymore."