![]()

September 15, 2003

Trying to Reshape Tibet, China Sends In the Masses

By JIM YARDLEY

| |

|

![]() HASA, Tibet —

Not far from Potala Palace, the hilltop fortress once home to Tibet's

exiled spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, and still a symbol of Tibetan

culture, the main commercial boulevard here has become a very different

symbol, of how Tibet is inexorably becoming more Chinese.

HASA, Tibet —

Not far from Potala Palace, the hilltop fortress once home to Tibet's

exiled spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, and still a symbol of Tibetan

culture, the main commercial boulevard here has become a very different

symbol, of how Tibet is inexorably becoming more Chinese.

Chinese restaurants sell dumplings on the sidewalk as street lights twinkle like neon sparklers. Shops offer Chinese music, DVD's and fashions. The faces on this street are mostly Chinese, too. The boulevard is even named Beijing Road, and it could pass for a noisy street in Beijing — which is what Chinese officials seem to have in mind.

For the Chinese government, which still describes its violent takeover of Tibet in 1950-51 as a "peaceful liberation," Tibet remains a prickly international issue, often defined by its sparring with the Dalai Lama over Tibetan autonomy. But the government's strategy, launched in recent years and now in full swing, is about the politics of economics.

The Chinese Communist government is reshaping Tibet with the force of China's superheated economy, pouring money and tens of thousands of Han Chinese into the region. The economic goal is to "modernize" Tibet's agrarian economy. But the political goal, analysts say, is to gradually secularize Tibetans and undercut political opposition with the fruits of capitalism.

For Tibetans, the question is whether this is economic development or economic imperialism. The influx of Chinese has divided cities like Lhasa intotwo worlds, Tibetan and Chinese. Some Tibetans say they have benefited from the Chinese strategy. But the Chinese in Tibet seem to be benefiting far more.

"You can be a bit richer here, and have more opportunities," said Su Zibo, 34, a Chinese businessman, explaining why he moved to Tibet five years ago to open a computer store. His biggest customers are government agencies.

In late August, government officials escorted foreign reporters on an eight-day tour of Tibet. Such a trip, once unthinkable, is less rare now, perhaps reflecting growing Chinese confidence over their control of a region that once seethed with separatist anger. In fact, government officials who once closed Tibet to the outside world are now wooing tourists, particularly from China itself.

In interviews and during unescorted forays, the changes roiling Tibet were evident at every corner. New buildings and roads were under construction seemingly everywhere. But new, expansive red-light districts, filled with Tibetan and Chinese prostitutes, were equally on display.

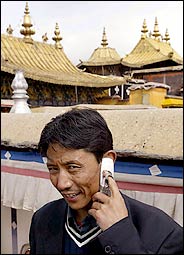

The tourism push has spawned hotels, restaurants and fleets of sport utility vehicles. On a recent day at the Jokhang Temple, the spiritual center of Tibetan Buddhism, a senior lama eyed a group of tourists and gently bemoaned the growing demands of the modern world.

He said he could study the ancient scriptures for only two hours a day because the rest of his time was spent maintaining the temple for visitors. "I am a student and this is my university," the lama, Nyima Tsering, said of the temple, "but now this is more like a museum and I am its keeper."

The local government now has a tourist slogan, "Take a Trip to the Holy Land." Yet the government still restricts religious activities by Tibetans and punishes public supporters of the Dalai Lama, who fled Tibet in 1959 when China sent in troops to suppress a revolt against its rule. So some Tibetans have private prayer rooms with forbidden photographs of him. In many monasteries, monks still whisper their support.

"He was born in Tibet, so he must come, he must come," a monk in Lhasa said furtively one afternoon.

The economic activity in Tibet is part of a larger plan introduced by Jiang Zemin to pour money and Han Chinese immigrants into the poorer and politically restive Western provinces, Tibet and Xinjiang. Xiang Ba Ping Cuo, governor of the Tibet Autonomous Region, said it was now the most heavily subsidized province in China, with 90 percent of its budget coming from government grants.

Perhaps the most problematic issue for Mr. Xiang Ba and other local officials is the changing ethnic makeup of Tibet as more Han Chinese arrive, many at the prodding of the government. Ta Jie, deputy mayor of Lhasa, said the central government regularly sent doctors, technicians and managers, usually on three-year contracts, often sweetened with the prospect of a promotion when they return home.

"When we lack those kinds of people, we will send a report to the central government," the deputy mayor said. "Then usually Beijing and Jiangsu Province will send us people."

With so many people moving in and out of Tibet, government population figures seem fuzzy. Mr. Xiang Ba said 92 percent of Tibet's 2.66 million people were ethnic Tibetans. But the percentage of Chinese is much higher in the cities, where the economic growth is occurring. In Lhasa, the provincial capital, the urban population, according to statistics, is at least 40 percent Chinese. Last year, a local official told Western reporters that urban Lhasa was almost half Chinese.

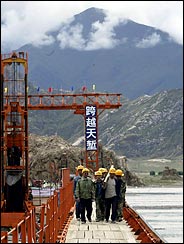

No project better illustrates the Chinese strategy, and the uneven benefits, than the Qinghai-Tibet Railroad. Set to be finished by 2007 at a cost of $3 billion, the railroad will tether Tibet more tightly to inland China, traversing an alpine landscape so rugged that skeptics still question the feasibility of the project. Chinese officials predict the line will become a vital trade route and transportation corridor for tourists.

Huang Difu, 41, an official overseeing the western half of the railroad, said the construction would ultimately employ about 38,000 people. But, he said, Tibetans could get as few as 4,000 or 5,000 of the jobs, and most would be for unskilled laborers who would earn about $8 a day, plus lunch. He said not a single Tibetan had been hired for skilled positions, which pay up to $2,500 a month.

The same cold economic reality could be found at the foot of Potala Palace. One afternoon, a Western reporter hailed cabs in search of a Tibetan driver. It took 14 tries. The driver said most Tibetans could not afford the roughly $20,000 needed to buy a cab and pay for licenses.

Not far away at the Barkhor, the ancient market surrounding Jokhang Temple in the old Tibetan section of Lhasa, shopkeepers say that Chinese merchants now run a majority of the stores that sell Tibetan trinkets, carpets and religious items to tourists and Buddhist pilgrims.

Kesang Takla, the Dalai Lama's representative for northern Europe, said such inequalities proved that the flood of Chinese investment and people into Tibet would ultimately harm, not help, Tibetans.

"It is very dangerous for the Tibetan people," she said. "Their very survival is threatened with the influx of the Chinese people."

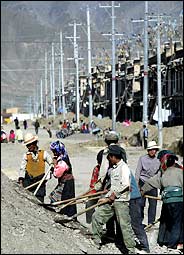

Yet some Tibetan workers on the lowest rungs of the economic ladder say their lives are improving. One night in the dark slums of the city of Tsetang, three teenage girls invited three Western reporters inside the room, 8 feet by 8 feet, where they live. They had no electricity and cooked on a small fire just outside the blanket they used for a door.

Laba, 16, and Lamu, 17, said they earned about $2.50 a day at construction sites, shoveling and carrying cement, working seven days a week, 12 hours a day. But they said life in rural areas was much harder. They manage to send money home to their parents, who farm and herd animals.

The girls giggled when asked about their only decorations: three advertisements from Chinese fashion magazines, including one showing a sleek Chinese model with the caption "Pretty." As for their lives, Lamu said, "Better every day."

Wang Lixiong, a Beijing author whose 1998 book about Tibet was banned in China, said the government's economic strategy had brought a measure of prosperity to some Tibetans, but he said the strategy's political goal was to make younger Tibetans more secular and less sympathetic to advocates of Tibetan separatism. He also said any appearance of a freer Tibetan society was misleading.

"It's a carrot-and-stick strategy," Mr. Wang said. "It combines the economic carrot with a political stick of continued repression."

An official at Tibet University confirmed, for example, that students faced expulsion if they were caught taking part in religious activities, like Buddhist pilgrimages. Earlier this year, China executed an ethnic Tibetan accused of involvement with bomb plots and Tibetan separatism.

"While to the outside world the government is making a show of relaxation and easing," Mr. Wang noted, "inside where you can see, any signs of separatism or nationalist sentiment are dealt with very harshly."

The monks who run Tibet's Buddhist monasteries are accustomed to Chinese scrutiny. A government agency regularly dispatches officials to "educate" monks and screens monks to determine who can be allowed to manage monasteries. Officials, meanwhile, emphasize their commitment to restoring monasteries and other "cultural relics" that were destroyed or damaged during the Cultural Revolution.

But the investments also seem intended to expand tourism. The number of tourists visiting Tibet, discounting the drop this year attributed to the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, in China, is growing rapidly. While the high altitudes once kept many Chinese away from Tibet, now, encouraged by Beijing, they are coming in droves, adding another dimension to the Chinese presence in Tibet.

"They say Tibet is very pretty and mysterious," said Long Ying, 16, who visited recently from Beijing, dragging along her father despite his fear of altitude sickness. "And there are a lot of deep religious things here."

Her father added, "It's a place we really, really want to see because this place has culture, and the culture of inland China is very different."