| History of Black Education: Washington and DuBois |

||

|

|

|

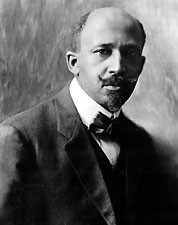

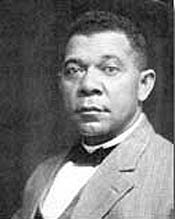

| Immediately following the Civil War, African Americans were faced with great discrimination and suffering. The

newly free slaves were faced with the dilemma of carving a niche in a society that once regarded them as nothing

more than property. During this period, two figures emerged as the preeminent leaders of two different philosophical

camps. Booker T. Washington of Virginia and William Edward Burghardt DuBois of Massachusetts, held two very different

proposals regarding the best way for African Americans to improve their situations. While their methods may have

differed, both of these remarkable men had a common goal in the uplift of the black community. Born in Franklin County, Virginia in the mid-1850s, Booker T. Washington spent his early childhood in slavery. Following emancipation, Washington (like many Blacks) felt that a formalized education was the best way to improve his living standards. Due to social segregation, the availability of education for blacks in was fairly limited. In response, Washington traveled to Hampton Institute where he undertook industrial education. At Hampton, his studies focused on the acquisition of industrial or practical working skills as opposed to the liberal arts. Because of his experiences at Hampton, Washington went on to become an educator as well as an adamant supporter of industrial education, ultimately founding the Tuskegee Normal and Agricultural Institute. Washington felt that the best way for blacks to stabilize their future was to make themselves an indispensable faction of society by providing a necessity. "The individual who can do something that the world wants done will, in the end, make his way regardless of his race" (Washington 155). As a Southerner himself, Washington was familiar with the needs of southern blacks as well as the treatment that they received. Washington stressed that Blacks should stop agitating for voting and civil rights not only in exchange for economic gains and security, but also for reduced anti-black violence. As such, his philosophies were more popular amongst southern blacks than northern blacks. Washington also garnered a large following from both northern and southern whites. Northern whites appreciated his efforts in a time when they were growing increasingly weary of the race problem; one that they associated with the South. Southern whites appreciated his efforts, because they perceived them as a complete surrender to segregation and self-uplift. Born in Massachusetts 1868 in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, W. E. B. DuBois grew up both free and in the North. Ergo, he did not experience the harsh conditions of slavery or of southern prejudice. He grew up in a predominately white environment, attended Fisk University as an undergraduate and later became the first African American to receive a doctorate from Harvard University. DuBois believe in what he called the "the talented tenth" of the black population who, through there intellectual accomplishments, would rise up to lead the black masses. Unlike Washington, DuBois felt that equality with whites was of the utmost importance. More politically militant than Washington, DuBois demonstrated his political beliefs through his involvement in the Niagara Movement, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and served as editor of The Crisis, a black political magazine. He felt that blacks should educate themselves in the liberal tradition, just as whites. DuBois' more radical approach was received well by other northern freemen. One of the biggest disagreements in philosophies between the two was over the issue of black suffrage. In terms of voting, DuBois believed that agitating for the ballot was necessary, but opposed giving the vote to the uneducated blacks. He believed that economic gains were not secure unless there was political power to safeguard them. This is shown in this comment from DuBois regarding Booker T. Washington: "He (Washington) is striving nobly to make Negro artisans business men and property-owners; but it is utterly impossible, under modern competitive methods, for workingmen and property-owners to defend their rights and exist without the right of suffrage" (DuBois 68). Washington, on the other hand, felt that DuBois' militant agitation did more harm than good and served only to irritate southern whites. "I think, though, that the opportunity to freely exercise such political rights will not come in any large degree through outside or artificial forcing…" (Washington 234). While there were many points of contention between Washington and DuBois, there were similarities in their philosophies as well. Both worked adamantly against lynching and opposed racially motivated violence. While Washington may have stressed industrial education over liberal arts, he did believe that liberal arts were beneficial (Washington 203). Furthermore, DuBois greatly appreciated and acknowledged many of Washington's noteworthy accomplishments (DuBois 68). Though both men can be criticized on various aspects of their approaches, both DuBois and Washington were key figures in the advancement of African Americans. |